The Soul Of A Butterfly (5 page)

Read The Soul Of A Butterfly Online

Authors: Muhammad Ali With Hana Yasmeen Ali

a

GOLDEN VICTORY

ON THE WAY

to and from Rome, I wore a parachute that I bought at an army surplus store. My plan was to drop to the floor as soon as the plane started shaking, with my parachute line ready in my hand, so I could jump out and pull the cord if our plane started to go down. I managed to distract my fear of flying by talking a lot, and before I knew it, we were in Italy. When I got to the Olympic village, I walked around introducing myself to people and shaking everybody’s hand. I even remembered most of their names. One of my teammates told me that if I had been running for mayor of the Olympic Village, I would have won the election. We all had a good time, and before long, I was an Olympic gold medalist.

When they put the gold medal around my neck, a boxer from Poland who won the silver medal was standing on one side of me, two boxers who shared the bronze medal were on the other side, the flag was waving, and the national anthem was playing. At the time I felt like I had defeated America’s so-called enemies. I stood there so proudly for my country. I felt like I had whupped the whole world for America.

I looked at my gold medal and said to myself,

I’m the champ of the whole world, and now I’m going to be able to do something for my people. I’m really going to be able to get equality for my people!

Before I left the Olympic Village a Soviet reporter asked me how it felt to win the gold medal for my country when there were restaurants in the United States where I couldn’t eat. I told him that we had qualified people

working

on that problem, and that I wasn’t worried about the outcome. I told him that I thought the United States was the best country in the world, including his. My spirits were so high, I wasn’t going to let anyone or anything bring me down.

When we arrived in Louisville, it had been twenty-one days since I had last seen my parents. That was the longest that I had ever been away from home. I walked off of the plane, wearing my gold medal. My mother, father, and brother were already standing there, along with the press and a small crowd. I read aloud for all to hear what would be my first published poem. I called it

HOW CASSIUS TOOK ROME

To make America the greatest is my goal,

So I beat the Russians, and I beat the Pole,

and for the USA won the Medal of Gold.

Italians said, “You’re Greater than the Cassius of Old.”

We like your name, we like your game,

So make Rome your home if you will.

I said I appreciate your kind hospitality,

But the USA is my county still,

’Cause they’re waiting to welcome me in Louisville.

As I walked down the streets of Louisville, with my parents and my brother beside me, I received a hero’s welcome.

There were Black and White crowds on the sidewalks; we had a police escort all the way downtown; my classmates from Central High were there, and the mayor told me that my gold medal was the key to the city. It all felt so good that I never let that gold medal out of my sight.

I wore it everywhere I went. I ate with it, showered with it, slept with it. I didn’t even take it off when the edges were cutting my back as I turned over in my sleep. Nothing could make me part with it, not even when the gold began to wear off. But, I did wonder sometimes why the richest nation in the world didn’t give its champions solid gold.

When the offers for management started rolling in, I didn’t pay them much attention at first, because I wanted Joe Louis to be my manager. But Joe was the quiet type, and he didn’t like loudmouth, bragging fighters, so he turned me down.

Joe must not have thought I was much of a boxer. He even predicted that I would lose all of my professional fights. I guess he wasn’t so smart after all.

My second choice was Sugar Ray Robinson. He was at the end of his career and I thought that he might be interested in managing me, but when I spoke to him, he told me to come back in a few years, he didn’t have the time.

It seemed like the only people who showed any interest in me were White southerners. One of the first contracts I was offered was from Joe Martin. I was not offered any cash advance, only the promise of seventy-five dollars a week for ten years. Needless to say, my father ripped it up immediately. So I ended up signing a six-year contract with ten Louisville millionaires. They became my sponsoring group. I received a ten-thousand-dollar advance, and they received 50 percent of all my earnings, in and out of the ring. It seemed like a good deal to me at the time.

I was really happy about that ten-thousand-dollar advance. It seemed like so much money. Our house had cost forty-five-hundred dollars and it was taking my father forever to pay it off, so ten thousand dollars sounded really good. Everything seemed to be working out for me. Even though I often thought about what happened with Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson, I didn’t hold a grudge toward either of them. They both did what they felt was right, and we eventually became friends.

Sugar Ray Robinson was there to support me in 1964 when I won the heavyweight title against Sonny Liston. As I stood before all of the cameras and the critics shouting “I am the greatest, I shook up the world!” Sugar Ray was on my left and Bundini Brown was on my right. They were both hugging me and laughing while trying to cover my mouth at the same time. It’s funny how things turn out in life. Sugar Ray later told me that he often wondered what might have been if he had been my manager, but I knew that everything happened exactly the way it was supposed to.

The last time I saw Sugar Ray Robinson was in his Los Angeles home. He wasn’t well then. I told him again how much he meant to me and that he was the greatest fighter who ever lived.

Then I told him that I was still waiting for that autograph.

The greatest victory in life

is to rise above the material things

that we once valued most

.

THERE COMES A

time in every person’s life when he has to choose the course his life will take. On my journey I have found that the path to self-discovery is the most liberating choice of all.

My Olympic gold medal meant so much to me. It was a symbol of what I had accomplished for myself and for my country. Although I still experienced some of the same racial discrimination that I always had, my spirits were so high that I thought all of that would change.

A Kentucky newspaper wrote that my gold medal was the greatest prize any Black boy ever brought home to Louisville. I was proud, but I remember thinking at the time, if any White boy ever brought back anything greater, I sure didn’t hear about it. It seemed that I had become Louisville’s Black “Great White Hope.” I expected my gold medal to achieve something greater for me. During my first few days home, it seemed to accomplish exactly what I hoped, but soon I had a rude awakening.

I was sure they were finally going to let me eat downtown. In those days almost every restaurant, hotel, and movie theater in Louisville and the entire South was either closed to Blacks, or had segregated sections. But I thought that my medal would open them up to me.

One day my friend Ronnie and I were riding our motor bikes around downtown Louisville, when it began to rain. We parked and walked into a little restaurant, where we sat down and ordered two cheeseburgers and two vanilla milk shakes.

I was so proud, sitting there with my gold medal around my neck. (I wore it everywhere in those days.) The waitress looked at both of us and said, “We don’t serve Negroes.”

I politely replied, “Well, we don’t eat them either.”

I told her I was Cassius Clay, the Olympic Champion. Ronnie pointed to my gold medal.

Then the waitress looked me over again and went to the back, to speak with the manager. Ronnie and I could see them huddled over, talking and looking back at us.

We were sure that now that they knew who I was we would be able to stay and eat, but when the waitress came back, she said that she was sorry, but we had to leave.

As Ronnie and I stood up and walked out of the door, my heart was pounding. I wanted my medal to mean something—the mayor had said it was the key to Louisville. It was supposed to mean freedom and equality. I wanted to tell them all that they should be ashamed. I wanted to tell them that this was supposed to be the land of the free. As I got up and walked out of that restaurant, I didn’t say anything, but I was thinking that

I just wanted America to be America.

I had won the gold medal for America, but I still couldn’t eat in this restaurant in my hometown, the town where they all knew my name, where I was born in General Hospital only a few blocks away. I couldn’t eat in the town where I was raised, where I went to church and led a Christian life. I still couldn’t eat in a restaurant in the town where I went to school and helped the nuns clean the school. Now I had won the gold medal.

But it didn’t mean anything, because I didn’t have the right color skin.

Ronnie wanted me to call one of the millionaires from my sponsoring group and tell them what happened, and I almost did, but more than anything, I wanted that medal to mean that I was my own man and would be respected and treated like any other human being. Then I realized that even if it had been my “Key to the City,” if it could get only me into the “White only” place, then what good was it? What about other Black people?

Later I realized that it was part of God’s plan for me that they wouldn’t serve me that day. Before I was kicked out of the restaurant, I was thinking what the medal could mean for me. The more I thought about it, the more I began to see that if that medal didn’t mean equality for all, it didn’t mean anything at all.

What I remember most about 1960 was the first time I took my gold medal off. From that moment on, I have never placed great value on material things. What really matters is how you feel about yourself. If I had kept that medal I would have lost my pride.

Over the years I have told some people I had lost it, but no one ever found it. That’s because I lost it on purpose. The world should know the truth—it’s somewhere at the bottom of the Ohio River.

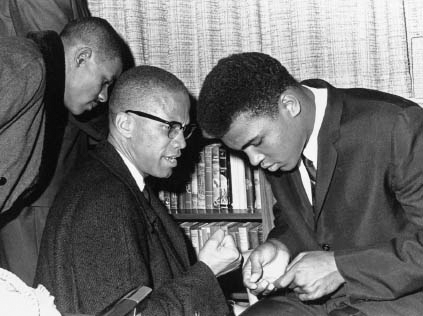

Studying with Malcolm X, 1963.