The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter (67 page)

Read The Sorcerer's Companion: A Guide to the Magical World of Harry Potter Online

Authors: Allan Zola Kronzek,Elizabeth Kronzek

Charges of sorcery might be brought by a disgruntled farmer against a neighbor, accusing him or her of harming animals or children, or causing a storm or a drought. Often these charges originated in village squabbles and had economic or vindictive motivations, but if evidence of traditional sorcery (such as a

curse

tablet or a wax doll) could be produced, a guilty verdict was likely.

Although sorcery continued to have some negative connotations, during the Renaissance a positive and even flattering use of the term developed in some circles. Scholars and physicians believed to possess the secrets of “white,” or beneficial, magic were called sorcerers. So were alchemists like

Nicholas Flamel

and

Paracelsus

, who struggled in their laboratories to create the Philosopher’s Stone (or

Sorcerer’s Stone

), a substance that would turn common metals such as lead, tin, or mercury into gold. Even Albus Dumbledore includes “Grand Sorcerer” among his many titles on Hogwarts letterhead. In common usage, a sorcerer became anyone with magical knowledge.

The image of a sorcerer as a super-wizard who can do anything was popularized worldwide by the 1940 animated film

Fantasia

, which featured a telling of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” Based on a story by the second-century Roman author Lucian (later retold by the German writer Goethe), the tale centers around a would-be magician who, in his master’s absence, brings a broom to life and orders it to fetch water from a stream. Although the apprentice is mistaken in thinking he can control the powers he summons (the broom won’t stop fetching water and the house floods), sorcery itself is portrayed as something marvelous, if obtainable only by a master magician.

or centuries, the legendary magical substance known as the Sorcerer’s Stone (or, more commonly, the Philosopher’s Stone) has embodied two of mankind’s most enduring dreams: eternal life and limitless wealth. Lord Voldemort hoped to steal the Stone from Hogwarts so he could use it to regain his strength and rise again to spread dark

or centuries, the legendary magical substance known as the Sorcerer’s Stone (or, more commonly, the Philosopher’s Stone) has embodied two of mankind’s most enduring dreams: eternal life and limitless wealth. Lord Voldemort hoped to steal the Stone from Hogwarts so he could use it to regain his strength and rise again to spread dark

magic

throughout the world. Countless others, both fictional and real, have sought the Stone to help them make gold or to create the Elixir of Life, a

potion

that would bestow immortality on whoever drank it.

The legend of the Sorcerer’s Stone evolved out of alchemy, an ancient art founded in Alexandria, Egypt, around the first century and dedicated to transforming common metals into silver or gold. As imagined by its originators, alchemy (from the Greek

kemeia

, meaning “transmutation”) was a scientific process, utilizing furnaces, chemicals, and laboratory apparatus. In went iron, lead, tin, mercury, and other metals and, after a series of secret operations, out came gold. That this could not possibly have happened (the laws of physics being no different then than now) did not stop the early alchemists from believing they had succeeded. They were, in fact, experts in coloring metals and producing alloys that looked like gold, contained some gold, and apparently passed for pure gold.

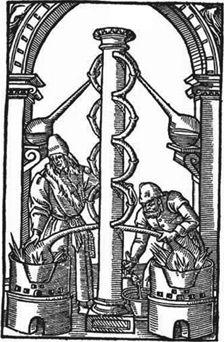

Alchemy was an extremely difficult pursuit with many opportunities for things to go wrong. These sixteenth-century alchemists seem more dazed and confused than enlightened

. (

photo credit 75.1

)

In the centuries that followed, alchemical knowledge was preserved and developed in the Arab world, and eventually entered medieval Europe around 1200 when the works of the Arab alchemists were translated into Latin. These manuscripts—filled with complex formulas and depicting sophisticated laboratory apparatus previously undreamed of—came as a revelation to the scholars and churchmen who read them. Apparently, a way of producing fabulous wealth had existed for more than a thousand years, and yet the best minds of Europe had known nothing about it. Now, seemingly, the method was at hand.

The lure of alchemy was irresistible. By the end of the fourteenth century alchemy was flourishing throughout all of Western Europe; most people had heard of it and there were hundreds if not thousands of practitioners. And a new idea had emerged. Instead of trying to turn lesser metals directly into gold, as the early alchemists had apparently done, medieval alchemists like

Nicholas Flamel

now spoke of producing a new substance—an extraordinarily potent catalyst that when added to common metals would trigger their transmutation, Midaslike, into gold. This new substance became known as the Philosopher’s Stone. As the lore about it grew, so did its imagined power to cure disease and prolong life indefinitely.

Although the Stone was by some definitions a magical substance, it was believed to have purely natural origins and therefore, in theory, could be made by anyone. But that did not mean it was easy to make. Manuscripts of alchemical instruction were difficult to locate and even more difficult to understand. Not only were they written in Latin (which only the clergy and the well educated could read), but also in order to protect the secrets of transmutation from falling into the wrong hands, alchemical writers deliberately obscured their meaning and wrote in what amounted to a secret code. For example, instead of using the common term

aqua regia

for the mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids, alchemists called it “The Green Dragon.” Lead was known as “The Black Crow.” Once you got through the process of deciphering these documents, if you ever could, you then needed the furnaces, metals, chemicals, and glassware required to set up an alchemical laboratory, and the patience to spend months or even years in pursuit of the elusive Stone. Nonetheless, many alchemists were willing to devote much of their lives to the task. Alchemy was thought to be a spiritual pursuit as well as a material one, and many alchemists believed that as long as they remained dedicated to their work, they too would eventually become “golden,” and evolve into a “higher self.”

With belief in the Stone so widespread, it was not surprising that enterprising swindlers developed a number of get-rich-quick schemes to separate would-be alchemists from their savings. Tricksters used sleight-of-hand techniques as well as mechanical devices to give the illusion of turning mercury into gold. Then they sold the stones that had supposedly caused the transformation (and sometimes the laboratory equipment and chemicals as well) to the gullible buyer. At the same time, both swindlers and sincere alchemists might put themselves in real danger by claiming to have the stone, for they could easily become the victims of thieves. For this reason, most alchemists operated in secret.

Alchemy remained a serious endeavor until the late seventeenth century, when its underlying theories were replaced by the more valid theories of modern chemistry. Although the alchemists never realized their impossible goals, they did discover many important chemicals useful in science and medicine; they also invented basic laboratory techniques and designed almost all of the chemical apparatus in use until the middle of the seventeenth century.