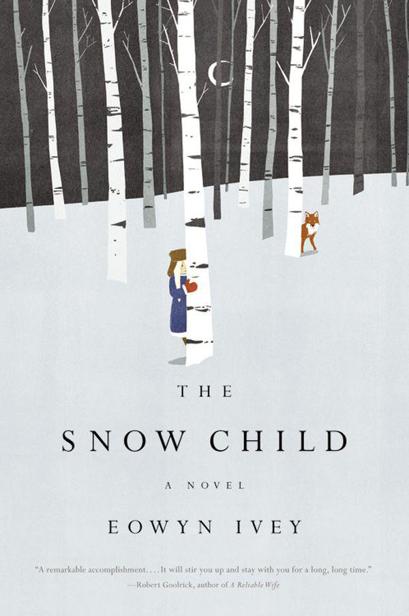

The Snow Child

Authors: Eowyn Ivey

For my daughters, Grace and Aurora

“Wife, let us go into the yard behind and make a little snow girl; and perhaps she will come alive, and be a little daughter to us.”

“Husband,” says the old woman, “there’s no knowing what may be. Let us go into the yard and make a little snow girl.”

—

Little Daughter of the Snow

by Arthur Ransome

Wolverine River, Alaska, 1920

M

abel had known there would be silence. That was the point, after all. No infants cooing or wailing. No neighbor children playfully hollering down the lane. No pad of small feet on wooden stairs worn smooth by generations, or clackety-clack of toys along the kitchen floor. All those sounds of her failure and regret would be left behind, and in their place there would be silence.

She had imagined that in the Alaska wilderness silence would be peaceful, like snow falling at night, air filled with promise but no sound, but that was not what she found. Instead, when she swept the plank floor, the broom bristles scritched like some sharp-toothed shrew nibbling at her heart. When she washed the dishes, plates and bowls clattered as if they were breaking to pieces. The only sound not of her making was a sudden “caw, cawww” from outside. Mabel wrung dishwater from a rag and looked out the kitchen window in time to see a raven flapping its way from one leafless birch tree to another. No children chasing each other through autumn leaves, calling each other’s names. Not even a solitary child on a swing.

There had been the one. A tiny thing, born still and silent. Ten years past, but even now she found herself returning to the birth to touch Jack’s arm, stop him, reach out. She should have. She should have cupped the baby’s head in the palm of her hand and snipped a few of its tiny hairs to keep in a locket at her throat. She should have looked into its small face and known if it was a boy or a girl, and then stood beside Jack as he buried it in the Pennsylvania winter ground. She should have marked its grave. She should have allowed herself that grief.

It was a child, after all, although it looked more like a fairy changeling. Pinched face, tiny jaw, ears that came to narrow points; that much she had seen and wept over because she knew she could have loved it still.

Mabel was too long at the window. The raven had since flown away above the treetops. The sun had slipped behind a mountain, and the light had fallen flat. The branches were bare, the grass yellowed gray. Not a single snowflake. It was as if everything fine and glittering had been ground from the world and swept away as dust.

November was here, and it frightened her because she knew what it brought—cold upon the valley like a coming death, glacial wind through the cracks between the cabin logs. But most of all, darkness. Darkness so complete even the pale-lit hours would be choked.

She entered last winter blind, not knowing what to expect in this new, hard land. Now she knew. By December, the sun would rise just before noon and skirt the mountaintops for a few hours of twilight before sinking again. Mabel would move in and out of sleep as she sat in a chair beside the woodstove. She would not pick up any of her favorite books; the pages would be lifeless. She would not draw; what would there be to capture in her sketchbook? Dull skies, shadowy corners. It would become harder and harder to leave the warm bed each morning. She would stumble about in a walking sleep, scrape together meals and drape wet laundry around the cabin. Jack would struggle to keep the animals alive. The days would run together, winter’s stranglehold tightening.

All her life she had believed in something more, in the mystery that shape-shifted at the edge of her senses. It was the flutter of moth wings on glass and the promise of river nymphs in the dappled creek beds. It was the smell of oak trees on the summer evening she fell in love, and the way dawn threw itself across the cow pond and turned the water to light.

Mabel could not remember the last time she caught such a flicker.

She gathered Jack’s work shirts and sat down to mend. She tried not to look out the window. If only it would snow. Maybe that white would soften the bleak lines. Perhaps it could catch some bit of light and mirror it back into her eyes.

But all afternoon the clouds remained high and thin, the wind ripped dead leaves from the tree branches, and daylight guttered like a candle. Mabel thought of the terrible cold that would trap her alone in the cabin, and her breathing turned shallow and rapid. She stood to pace the floor. She silently repeated to herself, “I cannot do this. I cannot do this.”

There were guns in the house, and she had thought of them before. The hunting rifle beside the bookshelf, the shotgun over the doorway, and a revolver that Jack kept in the top drawer of the bureau. She had never fired them, but that wasn’t what kept her. It was the violence and unseemly gore of such an act, and the blame that would inevitably come in its wake. People would say she was weak in mind or spirit, or Jack was a poor husband. And what of Jack? What shame and anger would he harbor?

The river, though—that was something different. Not a soul to blame, not even her own. It would be an unfortunate misstep. People would say, if only she had known the ice wouldn’t hold her. If only she’d known its dangers.

Afternoon descended into dusk, and Mabel left the window to light an oil lamp on the table, as if she was going to prepare dinner and wait for Jack’s return, as if this day would end like any other, but in her mind she was already following the trail through the woods to the Wolverine River. The lamp burned as she laced her leather boots, put her winter coat on over her housedress, and stepped outside. Her hands and head were bare to the wind.

As she strode through the naked trees, she was both exhilarated and numb, chilled by the clarity of her purpose. She did not think of what she left behind, but only of this moment in a sort of black-and-white precision. The hard clunk of her boot soles on the frozen ground. The icy breeze in her hair. Her expansive breaths. She was strangely powerful and sure.

She emerged from the forest and stood on the bank of the frozen river. It was calm except for the occasional gust of wind that ruffled her skirt against her wool stockings and swirled silt across the ice. Farther upstream, the glacier-fed valley stretched half a mile wide with gravel bars, driftwood, and braided shallow channels, but here the river ran narrow and deep. Mabel could see the shale cliff on the far side that fell off into black ice. Below, the water would be well over her head.

The cliff became her destination, though she expected to drown before she reached it. The ice was only an inch or two thick, and even in the depths of winter no one would dare to cross at this treacherous point.

At first her boots caught on boulders, frozen in the sandy shore, but then she staggered down the steep bank and crossed a small rivulet where the ice was thin and brittle. She broke through every other step to hit dry sand beneath. Then she crossed a barren patch of gravel and hiked up her skirt to climb over a driftwood log, faded by the elements.