The Sleepwalkers (225 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

This,

I

suggest,

explains

how

the

delusion

about

the

tides

could

gain

such

power

over

his

mind.

He

had

improvised

this

secret

weapon

in

a

moment

of

despair;

one

would

have

expected

that

once

he

reverted

to

a

normal

frame

of

mind,

he

would

have

realized

its

fallacy

and

shelved

it.

Instead,

it

became

an

idée

fixe

,

like

Kepler's

perfect

solids.

But

Kepler's

was

a

creative

obsession:

a

mystic

chimera

whose

pursuit

bore

a

rich

and

unexpected

harvest;

Galileo's

mania

was

of

the

sterile

kind.

The

tides,

as

I

shall

presently

try

to

show,

were

an

indirect

substitute

for

the

stellar

parallax

which

he

had

failed

to

find

–

a

substitute

not

only

in

the

psychological

sense,

for

there

exists

a

mathematical

connection

between

the

two,

which

seems

to

have

eluded

attention

so

far.

Galileo's

theory

of

the

tides

runs,

in

a

slightly

simplified

form,

as

follows.

2

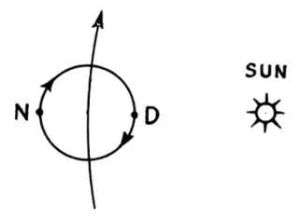

Take

a

point

on

the

earth's

surface

–

say,

Venice.

It

has

a

two-fold

motion:

the

daily

rotation

round

the

earth's

axis,

and

its

annual

revolution

round

the

sun.

At

night

when

Venice

is

at

N,

the

two

motions

add

up;

in

daytime,

at

D,

they

work

against

each

other:

Hence

Venice,

and

with

it

all

the

firm

land,

moves

faster

at

night

and

slower

in

the

daytime;

as

a

result,

the

water

is

"left

behind"

at

night,

and

rushes

ahead

of

the

land

in

daytime.

This

causes

the

water

to

get

heaped

up

in

a

high

tide

every

twenty-four

hours,

always

around

noon.

The

fact

that

there

are

two

daily

high

tides

at

Venice

instead

of

one,

and

that

they

wander

round

the

clock,

Galileo

dismissed

as

due

to

several

secondary

causes,

such

as

the

shape

of

the

sea,

its

depth,

and

so

forth.

The

fallacy

of

the

argument

lies

in

this.

Motion

can

only

be

defined

relative

to

some

point

of

reference.

If

the

motion

is

referred

to

the

earth's

axis,

then

any

part

of

its

surface,

wet

or

dry,

moves

at

uniform

speed

day

and

night,

and

there

will

be

no

tides.

If

the

motion

is

referred

to

the

fixed

stars,

then

we

get

the

periodic

changes

on

the

diagram,

which

are

the

same

for

land

and

sea,

and

can

produce

no

difference

in

momentum

between

land

and

sea.

A

difference

in

momentum,

causing

the

sea

to

"swap

over"

could

only

arise,

if

the

earth

received

a

push

by

an

external

force

–

say,

collision

with

another

body.

But

both

the

earth's

rotation

and

its

annual

revolution

are

inertial,

3

that

is,

self-perpetuating,

and

hence

produce

the

same

momentum

in

water

and

land;

and

a

combination

of

the

two

motions

still

results

in

the

same

momentum.

The

fallacy

in

Galileo's

reasoning

is

that

he

refers

the

motion

of

the

water

to

the

earth's

axis,

but

the

motion

of

the

land

to

the

fixed

stars

.

In

other

words,

he

unconsciously

smuggles

in

the

absent

parallax

through

the

back

door.

No

effect

of

the

earth's

annual

motion

relative

to

the

fixed

stars

could

be

found.

Galileo

finds

it

in

the

tides,

by

bringing

the

fixed

stars

in

where

they

do

not

belong.

The

tides

became

an

Ersatz

for

parallax.

The

power

of

the

obsession

may

be

judged

by

the

fact

that,

although

a

pioneer

in

the

field

of

the

relativity

of

motion,

he

never

discovered

the

elementary

error

in

his

reasoning;

seventeen

years

after

he

had

hit

on

his

secret

weapon,

he

still

firmly

believed

that

it

was

the

conclusive

proof

of

the

motion

of

the

earth,

and

presented

it

as

such

in

his

Dialogue

on

the

Great

World

Systems

.

He

even

intended

to

name

that

work

Dialogue

on

the

Flux

and

Reflux

of

the

Tides

.