The Sleepwalkers (22 page)

“What?” the box asks, “admiring my lasso, are you? I promise I’ll tell you all about it—once you’ve taken the evaluation.”

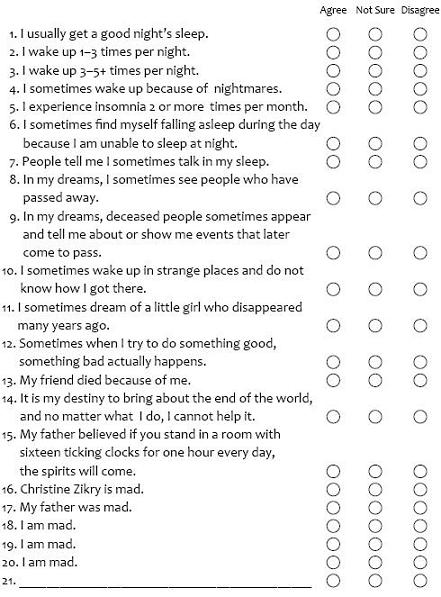

Caleb takes one more look around the room, then looks down at the paper and sees:

Patient name_____________________________________________________

Birthdate________________________________________________________

City of origin_____________________________________________________

PATIENT EVALUATION

STANDARD FORM

1

A

DIRECTIONS

: Please select the most appropriate answer by filling in the corresponding circle.

When he’s finished, he sets the pencil down. Already, he’s forgotten how he answered each question, as if the test were a dream that he hardly remembers upon waking.

The box crackles to life:

“About the lasso. Before I became director here, many years ago, I was a rodeo clown. That was during some of my wandering years, although some would argue that all my years have been wandering ones.

Rodeoing is tough business. I saw one man break his back, and another was gored to death not three feet from me. It was unsettling. The man who broke his back was a cowboy, but the one who got gored, he was a clown, like me. It’s funny, or rather not funny, because the clowns are taking on almost as much risk as the riders themselves, but, but, they get no respect, no fans. No love. But what nobody knew the whole time was that the man behind the makeup was actually faster and better than any of them, and could rope any living thing in the whole world. I always took pride in that.”

“What are you talking about?” says Caleb, confused.

“It’s just a little parable about making judgments before you fully understand things. And it happens to be a true story from my life.”

“What’s going on?” Caleb says. “How do you know all this about me? Did Christine tell you?”

The box crackles. “You’ll see,” it says.

“Look, you can keep me here, that’s fine. Just let Christine out. She doesn’t belong here. Take me instead.”

From the box comes the sound of a phone ringing. “Yes,” says the director’s voice, “ . . . his uncle, eh? Well, I don’t know . . . Let me ask him. Caleb? What’s your uncle’s name?”

Caleb frowns, not wanting to say the wrong thing. Given the paper on the desk, he figures if he lies, this man will know.

“I don’t have one,” he says. “Both of my parents are only children.”

“Did you hear that?” The director laughs. “Looks like we have an impostor. Let’s detain him and have our good friend, the sheriff, come and arrest him.”

“Arrest who?” says Caleb.

The box hisses in silence for a moment. “The gentleman who took you to Doctor Rodgers, a mister Ron Bent, I believe, seems to be posing as your uncle. He seems concerned for your well-being, isn’t that funny? He doesn’t know you’re safe and sound. Don’t worry, we’ll handle him.”

“Please,” says Caleb, “just let him go.”

“No,” the box says, “I don’t think so. Karl, please call Sheriff Johnson. And as for you, Caleb, you’re free to go. We don’t want to detain you. You have work to do.”

Caleb’s many questions (What do you mean, work? Where’s Christine? Why are you arresting that guy who helped me?) are left to wheel about in his brain, unanswered. The intercom box clicks off, and despite all Caleb’s efforts at communication, it won’t click on again.

Caleb just sits there for a moment, stung, staring at the piece of paper in front of him with his eyes half-closed, guarded.

When he finally gets up and approaches the door, he expects it to be locked. Instead, it opens right up, revealing an empty, darkened hallway. Caleb peers out into the hallway, and then glances over his shoulder, back at the office he had been sitting in. This might be the time to make a run for it, but his curiosity gets the better of him. He has to know what’s happening. It’s the budding journalist within him, he knows, the part that wants—needs—to make things coherent, to give them order, to put them together with a premise, support, a logical conclusion. Except he has no premise, only nonsense, a string of non sequiturs as far as the eye can see.

He closes the door leading to the hall and begins ransacking the office as quickly as he can. Instantly, disappointment envelops him.

The desk drawers: empty.

The filing cabinet: hundreds of folders, all empty.

The trash can: empty.

In fact, the only scrap of paper in the entire office is the “evaluation” the director had given him, and the only other object of any interest at all is the lasso, hanging on the hat rack.

The place is sterile.

There’s a soft knock at the door. Caleb’s heart races. He wants to run and hide, but there’s nowhere to go. The window is frosted and barred. He looks for a weapon, but there’s nothing, just the pencil and the coat rack, and he doesn’t think either one will do him much good. So if he can’t fight and he can’t flee, all he can do is go along for the ride.

“Come in,” he says, his voice sounding hoarse, his eyes locked on the door.

The man who opens the door is not the director.

At first, Caleb has trouble placing him (maybe because the drugs he was given are wearing off, maybe because his wrist is throbbing with pain again, so much that it’s difficult to think). After a moment, he realizes it’s the man from the front desk with the shaved head. Caleb surmises it might be Karl from the other end of the director’s phone.

“Hi, Karl,” he says.

“Hello, Mr. Mason,” says Karl. “Please, come with me.”

Karl is unarmed and seems as mild as milk. With no better option available, Caleb follows him.

They pass down a long hallway. Every other rectangle of fluorescent bulbs above is shut off, and the effect as they walk from light to darkness and into light again is a little painful to Caleb’s still-woozy brain.

They pass many doors on either side, each made of heavy oak and each bearing a number. Now he’s passing 333. There are sounds behind a few doors, a shuffling sound behind one, a sharp cough issuing from another, but mostly there is only silence. Finally, Karl leads Caleb to a lobby area with padded chairs and a fake flower arrangement on a big, laminated wood table. There is a bank of elevators, but Karl doesn’t push a button. Instead, he opens a door that leads to a stairwell of steel railings and peeling paint. Caleb follows him as he winds his way down and down with only the echo of their footfalls to mark their progress. When Caleb is sure they must be several stories underground, the man, Karl, pushes open another door. He gestures to Caleb, you first.

“Where am I going?” Caleb asks as he warily passes Karl, stepping through the doorway.

“Wherever you like,” Karl says, and Caleb, squinting, realizes that he has stepped into the light spilling through the front doors of the building. This is the main lobby.

“Thank you for visiting the Dream Center. We’ll see you again soon,” says Karl. He walks around the counter, sits down on a stool, and looks down at a magazine.

“I’m free to go?” asks Caleb.

“That’s right,” says Karl, without looking up. “The director saw no need to admit you.”

Caleb just stands there, frowning. Trying to figure out what’s going on right now makes his head hurt. He’d rather sort grains of sand on a beach. Finally, he decides to simply be direct.

“Karl, please tell me what’s going on.”

Karl looks up from his magazine, a little annoyed. “What do you mean? You can go,” he says.

“I know that,” says Caleb. “What I’m asking is what’s going on in the grand scheme of things here? Kids in this town are missing, my friend was abducted by—I don’t even know what, then all this. And Christine . . . Can you just please tell me what’s happening? Please?”

Karl looks a little amused. “Look, kid, it’s not my place to say. My job is the desk,” he says, and he thumps the palm of his hand on the counter.

“So you don’t know what’s going on either?” Caleb asks.

“Oh, no,” says Karl. “I know exactly what’s going on. I’ve been here since the beginning.”

“Then why won’t you tell me?”

“Because asking me is like . . . like asking the wick of a candle what the flame is going to do. A flame burns whatever it wants, it doesn’t give half a shit, excuse my French, what the wick thinks.”

“And who—or what is the flame?” asks Caleb. He feels that he’s close to something if this guy would just— But Karl only laughs.

“You mean you really can’t hear them, kid? They’re all around you. Tune in,” Karl says.

Karl’s words hang in the air for a second, and “who are they?” hangs on Caleb’s lips, but before the words can come out, the phone on the counter rings, and Karl snatches it up.

“Dream Center. . . . Of course, right away.” He hangs up.

“Who?” Caleb asks. “Who’s all around?”

But Karl is already disappearing out the door behind the desk. It slams shut, and Caleb is alone in the lobby.

His shadow stretches long at his feet from the light spilling in the doors, reflecting brightly off the polished floor. Somewhere far off, someone is yelling. Caleb shivers. He should be glad he can leave.

Glad he’s getting away. Christine isn’t as lucky. He takes a slow step through the doorway and out into the hush of impending twilight.

Should it be twilight now, or should it be morning? Time seems suddenly disjointed. He feels like he lost a day somewhere, but he’s not sure where. He walks up the gravel driveway on soggy legs. The wrist is aching bad enough to set his teeth on edge, but his jaw is slack, his eyes are slack, and his mind is adrift.

He finds his way to the car, still parked where he and Bean left it a lifetime ago. It starts right up. The only problem is there’s nowhere to go.

After what he’s seen, no place can be home again.

B

EFORE DARKNESS SETTLES IN

, Caleb kneels next to the car, parked in the driveway of his lost father’s house, and pulls the laces of his running shoes tight. He stretches, first one leg, then the other, then both, feeling the burn run along his sinews. The sun is lost behind the trees, but the color of the sky above is still vibrant, and he figures he still has a good half an hour until darkness marches in. When night comes he doesn’t know what he’ll do. He walks to the end of the driveway, looking at the woods all around him, eyes scanning the ferns for moving shapes, glancing at the treetops for lurking apparitions, finding none. When he reaches the road, he kicks into motion. At first, his legs feel heavy. He doesn’t know if it’s the drugs the doctor gave him, the fatigue (when was the last time he slept?), or simply the fact that he hasn’t run in a while, but for some reason, he’s dog-tired. Soon, though, all of it melts away: the leaden legs, the slight cramping in the chest, the pain in his wrist that strikes with every step. His surroundings, his pain, and the world, they all thin into one line of motion and become simple. Which is why he loves running so much in the first place.