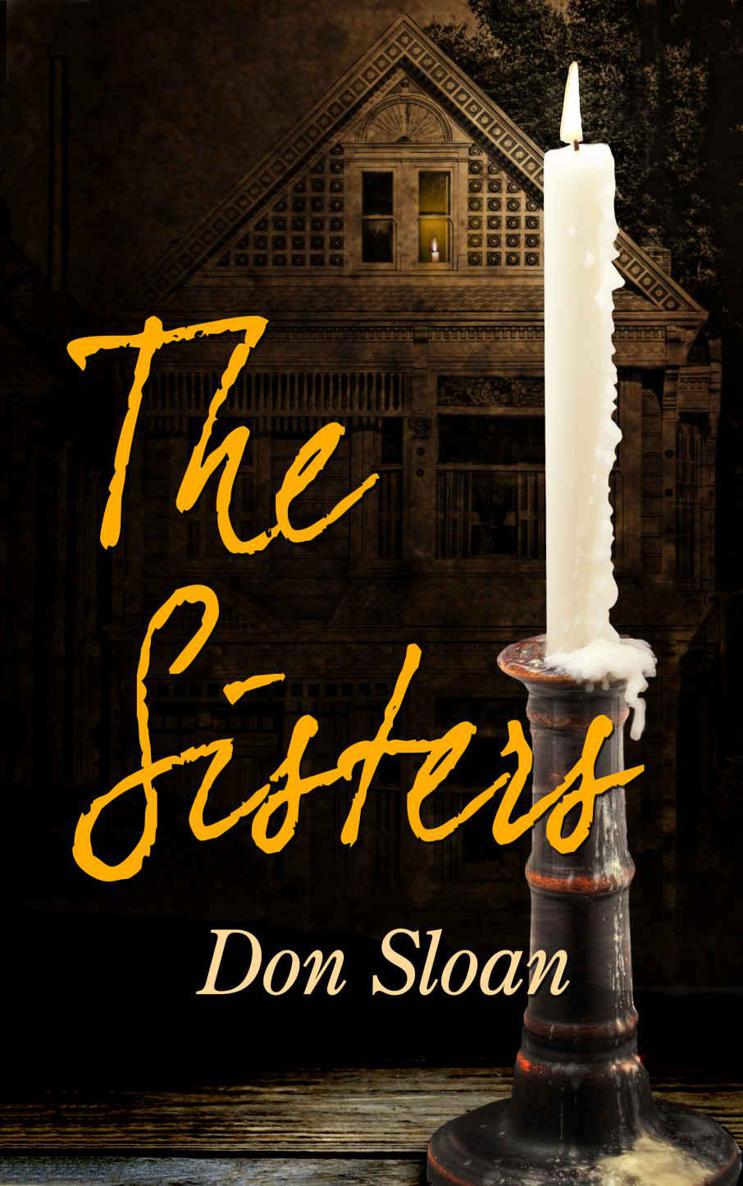

The Sisters: A Mystery of Good and Evil, Horror and Suspense (Book One of the Dark Forces Series)

Authors: Don Sloan

The Sisters

By

Don Sloan

Text Copyright ® April, 2014

By Don Sloan

All Rights Reserved

Thank you for downloading this ebook. This book remains the copyrighted property of the author, and may not be redistributed to others for commercial or non-commercial purposes. If you enjoyed this book, please encourage your friends to download their own copy from their favorite authorized retailer. Thank you for your support.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com or your favorite retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Thanks for downloading your FREE copy of

The Sisters

. Here is a Special Offer just for you!

***

Get Your FREE Sequel

--

The Horror Hunters

***

Become a Follower of my Free and Bargain book site and get your copy today!

Just Free and Bargain Books

is a unique site where you can download

free and deeply discounted books every day.

Click on the Menu tab and scroll to the bottom.

https://justfreeandbargainbooks.wordpress.com/

Thanks, and enjoy

The Sisters

!

Don Sloan is a master! This wonderful and suspenseful book, filled with historical information that builds the tale, is a must read. Mr. Sloan 's ability to weave the suspense from the past to the present (and the future!) and help the reader draw magnificent pictures of exactly what is happening...well, it's a fine work that deserves to be read. -- Doc Adams, Buffalo Tavern B&B

I never heard of Don Sloan, so I was excited to see his writing style. I'm a sucker for a good mystery or thriller. As I started reading, and realized that it revolved around older homes (another favorite of mine) so I was hooked. Each page is filled with informative narrative, and it reads so smoothly. I couldn't put the book down, so to speak, because I was anxious to delve into the story and quickly became hooked. -- CrichmanFreebies.com

The Sisters is the kind of horror book that allows the reader to suspend their grasp on the real world for a while and escape into a good story.

Well-written and fun. -- Winston Hill

To my wife Linda, for her love and continued

support through the years.

Thank you.

“Let the Games Begin!”

—Demetrius Vikulus, President,International Olympic Committee, Greece,1894

Cape May, New Jersey

February, 1939

The houses stand buttressed against the winter waves of the Atlantic. Huddled along the wide boulevard, they look far out to sea and shiver, their pale clapboard siding exposed to the raw wind.

There are fourteen houses along this stretch of Beach Avenue. Each house is fashioned like the next—three stories of gabled, Victorian secrets and whispered gossip, gathered carefully over the years and put away to discuss through the cold winters, when the owners and renters and summertime houseguests have long since packed their belongings and returned to other houses far from the shore.

For more than one hundred years these houses have squatted on this quiet, oceanfront boulevard, passing their secrets up and down, back and forth, so the first knows the last’s most intimate memories, and vice versa.

and she came into his room about three o’clock in the morning, with nothing on but a lace and cotton teddy

you don’t mean it

I most certainly do, and she didn’t have that on for very long

well, for heaven’s sake, and what a dear child she seemed to be, and only fifteen at that. You’d think her parents would have

run bootleg rum through the cellar door as though there wasn’t a law against it

my dear, you sound like you’ve never seen a real party. I’ll tell you, we had one here in, oh, I believe it was 1902 that could have set records around the

corner the market, he said

can he do that? I mean, isn’t there a limit to how much gold anyone can buy at one

apparently not. He says he can buy and sell

Pittsburgh. I’m sure she said she was from Pittsburgh

darling, you must be mistaken. If she had been from Pittsburgh, she would have known the Jamisons—not to mention the duPonts

well, she only talked about her friends the Lowensteins—they’re Jews, you know, and not fit for anyone to be around, if you know what I mean. Still, they have contributed a bit to our country’s prosperity, so I guess

that’s about all she wanted. She never was very strong. But she could have made a decent home for him if he had let her. Instead, there he was in the bathroom doorway, waiting for her. She didn’t even know he had come in, and he caught her right between the eyes

no!

yes, and the blood! My God, they scrubbed for a week and there are still stains on the wall and in the tub where he

punched the baby in the stomach over and over because it wouldn’t stop crying. And then she poured boiling water

over the banister to the tiled entryway. The girl’s head bounced once and then rolled under the

cellar, where he buried his first wife back in 1891. She had found out years before, of course, that he couldn’t

find the handle on the carving knife. It had come off during the scuffle. So she picked it up by the sharp end and beat his head in with the shaft and she cut off one of her own fingers in the process. Then, when the police

came home, he was waiting for her. Just waiting. With all the lights out, and the place quiet as a tomb. He had cut the wires, you see, but she didn’t know that. She locked and bolted the front door and reached for the entryway light switch. He came toward her in the dark and she must have felt him moving. She screamed. And screamed. And screamed.

The houses know each other’s secrets, all right. Know them all by heart, so that no one really knows whose story is whose anymore—not that it matters. What matters is the whispering in the dead of winter: the deep night murmur that becomes a dark chorus, alive with enthusiasm for the telling of the stories.

Snow pellets blow white across the boulevard and up onto the wide, night-shadowed porch of the house just in the center of the block. Inside, past leaded glass doors and heavy oak furnishings, something moves. Up the polished mahogany staircase, and up yet another flight to the third story something moves that has no breath, no warmth, no life.

There is a narrow passageway to the attic, locked behind a heavy door with steel bands. The shadow pauses at the door only long enough to pass cold fingers over the padlock. It falls heavily to the floor and the door opens. The shadow passes through, as quietly as a midnight breeze in an icy cold forest. Here, no light at all warms the creaking steps. It is darker than the inside of death.

In the attic, the bitter, knifing cold whirls and eddies around shapeless mounds of old memorabilia and the shadow moves silently to a dormer window. Cobwebs—spun by industrious spiders long dead—are brushed aside and a single candle is placed on the sill. And in the darkness a flame is struck.

Outside, the wind falls off to nothing, and snow drifts listlessly to the ground. The candle flickers briefly and catches, burning a pinprick hole in the vastness of the night.

Far out to sea, a single cry begins and then falls silent.

And in the dormer window, where the shadow has settled down to wait, the candle flares brightly and then goes out.

August, 1883

It is the summer in which the Claymore house is being built, along with three of its sister homes along the beachfront boulevard. The day is as open and welcoming as a maiden aunt —indeed, it is as warm as any in Cape May’s history, and the family that has come to tour the home and see its progress is one of Philadelphia’s most prominent. The mother is a small hen-like woman who frets and hovers over her two children as they run through and over the beams and new planking of the emerging structure. The father, Edmund Joseph Claymore Sr., is a brooding and silent man, skilled in business and eminently capable. He supervises the workers while the mother watches the children, a boy and girl, ages 8 and 10 respectively. Eventually tiring of the slow progress on the house, the children run for the shoreline, trailed by the mother. They begin unpacking a small bag containing colorful kites and string, bought in the village only that morning.

“Mr. Claymore, you can’t expect miracles,” the foreman of the job is saying to the businessman. The foreman is a solidly built man not more than 30 years of age, with a thick, coal-black handlebar mustache bristling above a line of great white teeth. He has been patiently explaining to the owner that his deadline for completion of the house within two months is impossible.

“I’ll expect what I damned well please,” Claymore says. “You Italians are all alike: too lazy to work and too stupid to do anything worthwhile.” Claymore, much smaller than the foreman, steps forward, as though moving in toward the man another six inches will make his position more clear.

“There is only one way I build a house, Mr. Claymore, and that is the right way, no matter how much time it takes,” says the foreman, a second generation Italian-American. His name is Carlos Androcci and the crew is one he has hand-picked for the job. They are craftsmen, each one a skilled carpenter, and they are constructing a work of art along the oceanfront boulevard. Claymore, however, cannot wait for perfection. Or, rather, he will not wait. Mrs. Claymore, on the beach with the children, has heard voices raised and is looking back toward the house—in time to see her husband throw an ill-aimed punch at the foreman, who deftly sidesteps it and brings his own knotted right fist into contact with the smaller man’s left temple.

The result surprises both men.

Claymore staggers back, eyes opening wider and wider, as though they are sucking in air instead of sight. His pupils begin to dilate and he windmills his arms on the way down to the hard oak planking. His legs refuse to support him any longer and he goes down hard, like fifty pounds of dropped floursack, like a hundred and fifty pounds of fish-eye-staring deadweight. His crisp, pressed suit props his torso up for a few seconds before finally allowing his body to slide to the meticulously mitered boards. And in the instant before death takes him, Claymore smells the clean, fresh aroma of wood recently harvested for the sole purpose of building his home.

Hands reach out to Androcci, who is stricken dumb with horror at the sudden death of his employer.

He cannot move, so his workmen, his friends, who understand better than he at that moment that he has forfeited his own life in taking that of Claymore’s, pull him away before the mother, who is now shrieking incoherently, can return to her husband’s side, before the children can stop laughing and pulling at each other’s kite strings, before Claymore’s rapidly cooling body can be the object of small-town police examination. They tug at Androcci’s big, muscular frame with increasing urgency, and yet he cannot move.

What evil fate is this, he wonders, that snatches his future so quickly from him―his carefully planned future in this wonderful country, where even a man born in a foreign land can raise a son who can make him proud, a son who constructs houses as perfect as ships in bottles, a son who can command a crew of impeccable craftsmen, all of whom can move as one body―one superb craftsman who can make a house that will stand for more than a hundred years?

Androcci turns reluctantly, in a time-delayed reality separate from the mother, who has run up onto the decking to begin brushing him away from her husband’s body, as though his mere lingering presence is finishing the Philadelphia businessman’s life and robbing her of everything she knows―everything she will ever know―everything her children will ever know.

The boy and girl also now have arrived and see the big foreman being bundled away like a celebrity, someone who has done a great thing and who is now being shielded from the sight and touch of mortals. They see him turn one last time to look upon the wreckage of his life, then move numbly away, surrounded by men speaking urgently to him in a language they do not understand. The mother goes on shrieking and wailing, but the children simply stand mute upon the fragrant floorboards, not yet aware that they have silently clasped hands.

The daughter, older than her brother by two years, has dressed that morning with infinite care in a starched white and blue pinafore, clasping her long auburn hair with a tortoise shell comb to keep it managed and out of her fair-skinned face. She is now watching, as she has always watched, for signs of how this might affect her and how she is supposed to react. Her mother is beyond control now, entering a state of hysteria from which she will never fully recover. The worksite is empty and neighbors are beginning to run toward them.

But the daughter continues looking at her father’s dead body, aware now only of a numb reality that seeps into her bones and soul like dark tidal waters.