The Sinking of the Bismarck (10 page)

Read The Sinking of the Bismarck Online

Authors: William L. Shirer

A Swordfish from the

Ark Royal

returns after making torpedo attacks on the

Bismarck. (Imperial War Museum)

A member of the torpedo crew aboard the

Dorsetshire

in the act of taking sights.

(Wide World)

Torpedoes from this British cruiser, the

Dorsetshire

, finally sank the mighty German battleship.

(Wide World)

A direct hit blasts the 42,800-ton

Bismarck

shortly before her sinking in the Atlantic.

(Wide World)

German sailors from the sunken

Bismarck

cling to rescue lines cast from a British cruiser. Many had to be abandoned in the cold sea.

(Combine Photos)

Survivors from the

Bismarck

land at a British port after being rescued at sea.

(Wide World)

Chapter Nine

An Eleventh Hour Turn of Fortune

Aboard the

Bismarck

toward the end of a stormy day Admiral Luetjens and his staff were waiting hopefully for the dark of night to arrive. The German Fleet Commander had known since 10:30 in the morning that he had been found again. At 11:54 he had radioed Naval Group West: “Enemy aircraft shadowing. Land plane. Approximate position 48 40N, 20 00W.” This was 600 miles from Brest, his destination.

A little later he reported that a wheeled plane was circling him. From German intelligence furnished him from shore he knew what that meant. It meant that enemy Force H, with the battle cruiser

Renown

and the aircraft carrier

Ark Royal

,

was near. The news had an ominous sound to naval headquarters in Berlin. “This marked,” said the official German naval report later, “the beginning of the unfortunate developments.”

Still, to those aboard the

Bismarck

it had not been a bad day. Though British carrier planes had maintained contact throughout the afternoon, none of them had launched a torpedo attack. Admiral Luetjens had expected one. But it had not come. (He had no idea that the

Ark Royal

’s Swordfish had attacked their own ship.)

It was now past 7:00

P.M.

on May 26. Evening was almost upon them. Two more hours of dwindling daylight and the

Bismarck

would be safe. The planes from the enemy carrier, which were still hovering about, could not keep up their watch after dark. A British cruiser had been spotted on the horizon at 5:40

P.M.

But Admiral Luetjens thought it probably could be shaken during the night.

At dawn—all would be over. The

Bismarck

would be under the cover of the mighty Luftwaffe. The Admiral had already received a radio message from Reich Marshal Hermann Goering,

chief of the German air force. It said that the Reich Marshal had ordered the mobilization of every German airplane available in western Europe. They would provide protection to the

Bismarck

on her way in to Brest. And U-boats and destroyers would help.

In another twenty-four hours or so Admiral Luetjens’ daring mission would be successfully completed. Although he had not succeeded in the original aim of destroying British merchant shipping, he and his gallant crew would certainly be hailed in Germany for having sunk Britain’s greatest warship, the

Hood

, with no loss to themselves. And they would be congratulated for having, after their great victory, eluded most of the ships in the British navy and got safely back to port.

In fact, according to his dispatches, Admiral Luetjens’ chief worry at twilight that evening was his fuel supply. It was getting low. At 7:03

P.M.

he therefore signaled home: “Fuel situation urgent. When can I expect fuel?” Probably his message was designed more to stir up Naval Group West than to get oil. For though Group West

replied that it was sending out the tanker

Ermland

to refuel him during the night, the Fleet Commander knew that the ship could never get through the British, nor could he afford to stop to take on oil. He had enough fuel to make Brest at twenty knots. He merely wanted to arouse the naval command ashore.

It had been signaling him for twenty-four hours that help in the form of Luftwaffe bombers, U-boats and destroyers was on the way. None had materialized that he could see. Like most German naval officers, Admiral Luetjens resented the fact that Hitler and Goering had not given the German navy a fleet air arm such as the British had. The droning of two planes from the

Ark Royal

just out of his gun range was a reminder to him of how useful carrier planes were to the enemy.

Still, though the British had known his position since before noon and their carrier could not be far away, they had done nothing about it. They had refrained from attacking all through the long afternoon. Now they had only an hour or so more of waning daylight in which to try. Perhaps the

weather was too bad, the visibility too low, the waves too high, to mount an air attack from a carrier. Luck had been with the Germans insofar as the weather was concerned.

But even if the British planes did come through at the last minute, what damage could they do? The light torpedoes which the antiquated little Swordfish biplanes carried could scarcely penetrate the heavy anti-torpedo armor of the

Bismarck

. It had been built to withstand the heavier torpedoes of surface ships. Admiral Luetjens was not unduly downhearted as he stood on the bridge of the

Bismarck

toward 8:30 that evening. He was scanning the eastern skies for the coming night that would preserve his ship and his victory.

And then the antiquated little enemy planes appeared.

The air-raid alarm sounded throughout the battleship. A voice blared through the loud-speakers: “All hands to action stations!” From the lookouts came cries: “Plane on the starboard bow!… Plane on the port beam!… Plane on the starboard quarter!”

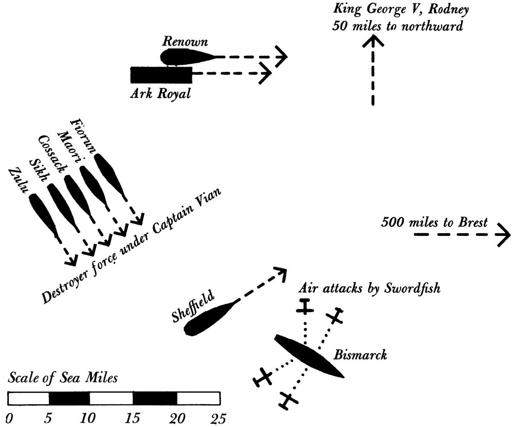

Torpedo Attacks on the Bismarck

The situation about 8:54 P.M., May 26.

The old-fashioned Swordfish, one of the few types of biplanes still being used in combat, were swarming in from all directions. The

Bismarck

’s guns roared into action, puncturing the sky with the bursts of their shells.

Admiral Luetjens hastily got off an urgent radio message to shore: “20:54. [8:54

P.M.

] Am being attacked by carrier-borne aircraft!”

On the

Ark Royal

, as daylight started to fade, the crew was working feverishly to get off the second and final strike against the

Bismarck

. All hands knew it was the last chance.

The fiasco of the attack on the cruiser

Sheffield

had at least revealed one vital piece of information to the carrier’s commander. Captain Larcom, restraining his feelings about having been nearly sunk by the

Ark Royal

’s planes, radioed over to Captain Maund that most of the torpedoes launched by the Swordfish had exploded on hitting the water. In fact, that had saved the

Sheffield

from disaster.

Captain Maund on the

Ark Royal

concluded at once that the new magnetic pistols on his aerial torpedoes would have to be discarded. He ordered them replaced by the old-fashioned contact pistols. These went off only when they hit a solid object. In the high waves, torpedoes tended to dive lower than they were set to go. They often went

under

a ship. Theoretically a magnetic torpedo, even when it slid under a ship, would explode because of its nearness to the steel of a vessel’s hull. That was why Captain Maund had

used them in the first attack. But for some reason most of them had gone off on hitting the water. He therefore decided to try the old contact kind. To guard against their diving harmlessly under the

Bismarck

, he set the torpedoes for a diving depth of only ten feet.