The Silk Road: A New History (36 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

As the rulers sponsored the mass copying of Buddhist sutras in the hope of generating merit, so too did they finance the construction of new caves. The sixty-six caves built in the Tibetan period have several distinguishing characteristics: they often feature mandalas, or diagrams of the cosmos, among other elements from esoteric Buddhism. Cave paintings from this period also grant greater prominence to the donors, especially the Tibetan emperor.

62

During the Tibetan period, Dunhuang artists painted Mount Wutai, and they continued to do so in the tenth century, when Dunhuang came under Cao-family rule. One of the most magnificent caves at Dunhuang, cave 61, dates to just around 950.

63

The upper section of the entire western wall of the cave, a section measuring 11.5 feet (3.5 m) tall by 51 feet (15.5 m) wide, shows the Mount Wutai pilgrimage site in Shanxi Province. The top of the painting shows a heavenly assembly, while the middle shows ninety different buildings at Mount Wutai, each bearing a label, and the bottom shows travelers on their way to the mountain. The painting is not an accurate map of the pilgrimage site; it probably was intended as a guide for viewers unable to visit the site themselves. The cave’s patrons included Cao Yuanzhong, the ruler of Dunhuang from 944 to 974, and his wives, one of whom was from Khotan.

Despite occasional outbreaks of armed conflict, the rulers of Dunhuang maintained contact with both the Tang and India during the Tibetan period. Monks and envoys, dispatched by the rulers of Tibet, China, and India, traveled between Tibet and China, and they often stopped at Dunhuang during their travels. The lack of circulating currency did not prevent envoys and monks from proceeding from one oasis to the next; much as they had in earlier periods, rulers provided emissaries with escorts, transport, and food.

In 848 a Chinese regime reestablished control at Dunhuang, but the use of Tibetan persisted. Earlier generations of scholars assumed that the Tibetan-language materials in cave 17 must have been written before 848; more recently scholars have come to realize that Tibetan remained in use as a lingua franca even after 848.

64

Under Tibetan rule, the pilgrimage route from Tibet to Mount Wutai, which passed through Dunhuang, saw an increase in traffic. Also from the library cave are copies of five letters of introduction, in Tibetan, for a Chinese monk traveling to Tibet; they, too, date to the period after 848, when Chinese armies expelled the Tibetans from Dunhuang.

65

The letters explain that the monk is going to India to study at the great Buddhist center at Nalanda and to obtain relics. Beginning his journey at Mount Wutai, the monk visited several towns on the way to Dunhuang, where he left the letters behind, presumably because he did not need them in Tibet.

Another Tibetan-language manuscript was dictated by an Indian monk to a Tibetan disciple who could understand some Sanskrit but made many spelling mistakes. The document explains that in 977 (or possibly 965), the Indian monk Devaputra traveled from India to Tibet and then to Mount Wutai; on his way back, near Dunhuang, he bestowed his teaching on a disciple. The text gives many technical terms in Tibetan, followed by the approximate Sanskrit spelling.

66

Tibetan monks encouraged the study of Sanskrit, possibly because their own alphabet was modeled on Sanskrit, making it more accessible.

67

At least some monks must have spoken Sanskrit to communicate, most likely with other learned monks, in monasteries just as Xuanzang did on his way to India.

In 842, when the confederation of peoples who had supported the rulers suddenly broke apart, the Yarlung dynasty collapsed, and Tibetan control over Dunhuang weakened. In 848 the Chinese general Zhang Yichao organized an army that expelled the remaining Tibetans.

68

The Tang dynasty was much weaker than it had been before the An Lushan rebellion. Even within central China (the area often called “China proper,” which includes the Yangzi, Yellow, and Pearl River valleys), the Tang had ceded political control to military commanders who collected taxes and financed their own armies, sometimes sending some revenues to the center. Like these commanders, Zhang Yichao received the title of military governor from the Tang court in 851. Zhang pledged allegiance to the Tang dynasty but in fact governed Dunhuang as an independent

kingdom. Under Zhang family rule, Dunhuang sent envoys to the Tang capital at Chang’an to present tribute to the Tang emperor, much as other independent Central Asian rulers did.

Zhang did not gain complete control in 848; his armies fought those of the Tibetans again in 856, as a literary text entitled “Zhang Yichao Transformation Text” relates. Of all the literary genres represented in cave 17, transformation texts, which alternate passages of prose with poetry, are the most distinctive. Transformation texts combine stretches of sung poetry and recited prose (this literary genre existed in Kuchean, too). The library cave preserved thirty or so examples of Chinese-language transformation texts; they survive nowhere else.

69

Most broadly, the term “transformation” refers to the different transformations of creation; monk storytellers performed these tales to help their audience members escape from the cycle of life, death, and rebirth from which all Buddhist teachings offered escape. Transformation texts contain a tell-tale formula: “Please look at the place where [a specific event] happens; how does it go?”

70

As they narrated these tales, storytellers pointed to scenes in scroll paintings so that the audience could picture the events they described.

The Zhang Yichao transformation text, which describes several battles in 856 between Zhang’s army and the tribes fighting on the Tibetan side, sets the scene using words:

The bandits [the Tibetan coalition] had not expected that the Chinese troops would arrive so suddenly and were totally unprepared. Our armies proceeded to line up in a “black-cloud formation,” swiftly striking from all four sides. The barbarian bandits were panic-stricken. Like stars they splintered, north and south. The Chinese armies having gained the advantage, they pursued them, pressing close at their backs. Within fifteen miles, they caught up with them.

Then, just as the narrator points to a scene showing the army, he says, “This is the place where their slain corpses were strewn everywhere across the plain.”

71

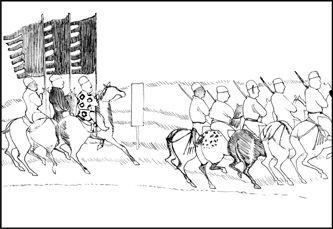

None of these scroll paintings survive, but a cave painting done in 861 does show Zhang’s army on parade.

72

This cave was completed in 865. Four years earlier, General Zhang Huaishen, the nephew of the Chinese ruler Zhang Yichao, began work on the cave, the first to be financed by a member of the ruling Zhang family. The inscription explains that Zhang Huaishen

had a strong desire to carve a cave. He looked around the whole area, but there was no place at all, except for a single cliff, where cutting was possible. Undaunted by the enormity of the work to be accomplished, his spirit was concentrated to the point where it could pierce stone, his purpose strong enough to move the mountain.

ZHANG YICHAO’S ARMY

Zhang Yichao’s troops carry fluttering banners. Some figures wear plain robes favored by the Chinese, while others are dressed in brightly patterned fabrics often worn by Uighurs and other non-Chinese peoples. The painting offers a glimpse of the diverse peoples who supported Zhang-family rule. Drawing by Amelia Sargent.

Then he prayed to the heavenly spirits above, gave thanks to the earth spirits below, divined to find an auspicious time, and calculated the day for the work to start. The cutting and chiseling had hardly begun, when the mountain split of its own accord; not many days had elapsed, when the cracks opened to a hole. With further prayers and incense, the sands began to fly, and early in the night, suddenly and furiously, with a fearful rush, there was the sound of thunder, splitting the rock wall, and the cliff was cut away.

73

The author offers a step-by-step account of how to make a cave: workmen started by digging a crack, which they gradually expanded until it could hold wall paintings and statues. The process of digging a cave was labor-intensive but did not require the use of expensive materials. Local artists lived on site, in the northern cave complex, where archeologists have found numerous artists’ workshops, some complete with pots of paint.

74

In the ninth century most artists belonged to local workshops, and by the mid-tenth century the local government had established a painting academy staffed by artist-officials.

75

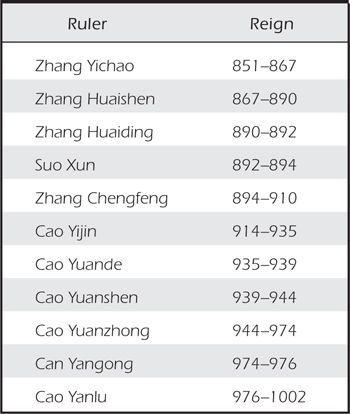

TABLE 6.1 THE RULERS OF INDEPENDENT DUNHUANG, 851–1002

Like the Tibetan rulers before him, Zhang Huaishen and his successors sponsored the construction of many new caves. Building a cave was an intensely religious act: when one ruler decided to dig a cave, he and his wife ate vegetarian food for an entire month and then lit lamps, burned incense, and paid monks to pray and copy sutras, all in the hope of generating Buddhist merit. Only then did they begin construction of the cave.

76

Some of the caves at Dunhuang contain portraits of Zhang Yichao and the rulers who succeeded him: around 925 Cao Yijin, who had taken over from the Zhang family in 914, commissioned a series of portraits of his predecessors in cave 98. On viewing these portraits, any visitor might imagine, as the Cao-family donors surely desired, that the order of succession had been smooth. In fact it was anything but. Zhang Yichao’s nephew Zhang Huaishen succeeded him on his death in 867 and ruled until 890, when his cousin, a son of Zhang Yichao, killed him, his wife, and six children. The new ruler, Zhang Huaiding, ruled for a year before dying a natural death; the next ruler came to the throne as a minor and was overthrown by his guardian Suo Xun. In 894 the former ruler regained power and stayed on the throne until 910. The last years of Zhang-family rule coincided with the closing years of the Tang dynasty, a time of great political uncertainty, when the emperors were first held prisoner and then overthrown in 907.

77

In 915 Cao Yijin, the son-in-law of the last Zhang-family ruler, took the throne, and his family ruled until 1002. After that year records do not refer to any Cao by name, suggesting that the Uighur Kaghanate based in Ganzhou (now Zhangye, Gansu Province), had gained control of Dunhuang. In the eighth century the Uighurs had originally been united, but broke apart in 840 following the Kirghiz destruction of the unified Uighur Kaghanate, which prompted Uighurs to flee to both Turfan (the Western Uighur Kaghanate included Beiting, Gaochang, Yanqi, and Kucha) and Ganzhou, the site of a second, smaller kaghanate.

78

In 1028 the Uighur Kaghanate at Ganzhou fell to the Tanguts, and in the 1030s Dunhuang followed, both becoming part of the Xi Xia realm, which included part of northwest China. We know little about the power struggles after 1000, simply because no materials from cave 17 or any other excavated documents describe these events in detail.

Between 848 and 1002, just as during the preceding period of Tibetan rule, the travelers who appear most often in the documentary record are envoys and monks. The Zhang and Cao families maintained diplomatic relations with all of their neighbors; they sent and received gift-bearing missions from the Tang capital at Chang’an and from other closer rulers as well, most notably the rulers of Khotan and the Uighur Kaghanates.

79

Although many documents record the coming and going of emissaries, few detail what gifts they presented and what they received in return. For that reason one inventory of gifts given and received by a delegation that traveled to Chang’an in 877 is particularly important.