The Silk Road: A New History (12 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Kucha’s most famous native son, Kumarajiva (344–413), produced the first understandable translations of Buddhist works from Sanskrit into Chinese, greatly facilitating the subsequent spread of the new religion into China.

1

He was the lead translator of some three hundred different texts from Sanskrit into Chinese, of which the most famous is the Lotus Sutra. (Sutra is the Sanskrit term for a work credited to the Buddha; in fact, many took shape long after his death around 400

BCE.

) Even though subsequent translators tried to improve on Kumarajiva’s work, many of his translations, prized for their readability, continue to be used even today.

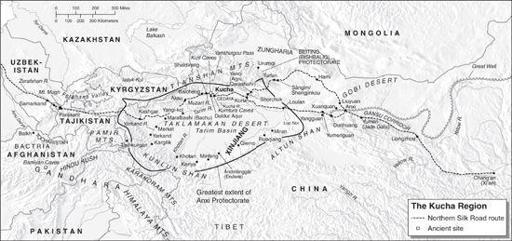

Kumarajiva was an unusually talented linguist, who, like many of Kucha’s residents, had mastered multiple Central Asian languages including his native Kuchean, Chinese, Sanskrit, Gandhari, and possibly Agnean and Sogdian as well. Kumarajiva’s father spoke Gandhari in his homeland of Gandhara, as did the immigrants to Niya. Sogdian prevailed in the area around Samarkand, and Agnean was used along a stretch of the northern Silk Road centered on the settlement of Yanqi, roughly 250 miles (400 km) to the east of Kucha. Yanqi is the Chinese name; the Uighur is Qarashahr. Kumarajiva and his colleagues used the Brahmi script to read and write Kuchean and Sanskrit, and they may also have studied the Kharoshthi script, which stopped being used around 400.

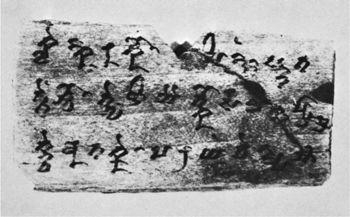

A SILK ROAD TRAVEL PASS

This travel pass in the Kuchean language, measuring 3 ¼ inches (8.3 cm) by 1 ¾ inches (4.4 cm) and written in Brahmi script, gives the name of the official inspecting a party of travelers going through a border station, the official to whom he is sending the report, and the name of the person carrying the pass. Over one hundred such passes have been found, which usually continue by listing the people and the animals traveling together, information missing from this document. Written with ink on notched poplar wood, these passes originally had a cover tied with twine and sealed, but no intact examples survive. Courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

This chapter will discuss these languages, especially the immense intellectual effort to understand the lost languages of Kuchean and Agnean after 1892. Scholars around the world spent almost one hundred years translating Kuchean, not only to decipher the language but also to understand how it differed from the closely related Indo-European language Agnean. The effort proved most worthwhile.

In Kumarajiva’s lifetime, work began on building the world-famous caves of Kizil, located 42 miles (67 km) to the west of Kucha. The caves are one of the most appealing tourist sites in Xinjiang, and can be visited today by taking a car, train, or plane to Kucha or Korla, and then by ground transportation to the valley where the caves are located. But in the past, until about a century ago, almost everyone came by boat, down the many rivers fed by glacial runoff that flowed through the Taklamakan Desert. The largest river, the Tarim, runs along the northern edge of the desert, and two of its tributaries are near Kucha, the Kucha River and the Muzart River, which passes directly in front of the Kizil caves. The heavy demand for water in northwest China means that these rivers now carry much less water than they did in the past. Today, if one wants to cross the desert by boat, it has to be done in the early spring, when the water levels are at their highest. A century ago these rivers were navigable most of the year, except when blocked by ice.

To understand how dramatically different the Kucha region was just a century ago, one only has to read the splendid account by Sven Hedin of Sweden. In the fall of 1899 he purchased a barge 38 feet (12 m) long with a shallow draft of just over a foot (30 cm). The deck accommodated Hedin’s tent, his darkroom, and a clay fire pit for cooking. Alerted that the river would narrow near Maralbashi (modern-day Bachu), he bought a second boat “less than half the size” of the barge, and the two boats traveled together (see color plate 10).

Hedin began his voyage in the far western corner of Xinjiang in Yarkand, just southeast of modern Kashgar. He vividly depicted his departure on September 17, 1899, from the Lailik pier in Yarkand: “The wharf presented a lively scene. Carpenters were sawing and hammering, smiths were forging, and Cossacks [guards hired by Hedin] supervised the whole scene.” On that day, Hedin recorded the width of the river at 440 feet (134 m) and the depth at 9 feet (3 m).

2

After six days, Hedin reached the point where the Yarkand River divided into several smaller streams, each with its own perils.

The river-bed narrowed. We were carried along at breakneck speed by the current. The water seethed and foamed around us. We flew down a rapids. The passage was so narrow, and the turns so abrupt, that the boats could not be steered off; and the big boat struck the shore so violently, that my boxes were nearly carried overboard.… The water swirled all the way; and we moved so swiftly, that the barge nearly capsized when we struck the ground violently.

Suddenly the rapids ended, trapping the larger barge in the mud. It took thirty hired men to carry the barge overland so that the trip could resume.

Continuing down the river, Hedin followed the Yarkand River north to where it met the Aksu River, entering from the north, forming the start of the Tarim River. Hedin continued through the Taklamakan Desert, floating east. For leisure, he would go sailing on the smaller craft, while the larger barge followed behind. The river continued to flow at a vigorous pace of some 3–4 feet (1 m) per second, but the chunks of ice in it became larger and larger until, after an eighty-two-day trip that had taken him nearly 900 miles (1,500 km), Hedin called an end to his river journey at Yangi-kol, three days’ travel from the oasis of Korla.

3

Had Hedin departed earlier in the summer, he could have gone the full distance to Kucha, still slightly more than 200 miles (300 km) away.

Hedin’s exploration aroused great interest in Europe, leading to the organization of British, French, and German expeditions. The Germans launched three expeditions in quick succession. After literally tossing a coin, the leader of the third expedition, Albert von Le Coq, decided to go north to Kucha and arrived at the Kizil caves in 1906. He found one of the most beautiful religious sites in all of China, with a total of 339 caves carved into a hillside along a one-mile (2 km) stretch.

4

Some caves are small, while others range from 36 to 43 feet (11–13 m) in height and are 40 to 60 feet (12–18 m) deep. The Muzart River flows four miles (7 km) to the south. An oasis in front of the caves creates a lovely natural setting, where one can occasionally hear a cuckoo—a rare sound in modern China.

The Kizil hillside is composed of conglomerate, a rock so soft that caves could be easily carved out. It also made the caves fragile, so the original diggers often left a central pillar in the middle of caves for support. Over the centuries, earthquakes have done grave damage to the site, causing the outer rooms to collapse, leaving the interior rooms sometimes totally exposed to the elements. Le Coq described such an earthquake he and Theodor Bartus and their crew experienced in March, 1906:

A strange noise like thunder was followed quite suddenly by a great quantity of rocks rattling down from above.… The next moment—for everything happened with amazing speed—I saw Bartus and his workmen hurrying down the steep slope, and a procession of my Turkis [Uighurs], screaming after! I followed them, too, and in a flash we were down in the plain, pursued by great masses of rock, tearing past us with terrifying violence, without a single one of us being hurt—why or how I cannot understand to this very day!

I turned my eyes in the direction of the river and saw its waters in wild commotion—great waves beating against its banks. In the transverse valley, farthest up the stream, there suddenly rose an enormous cloud of dust, like a mighty pillar, rising to the heavens. At the same instant the earth trembled and a fresh roll, like pealing thunder, resounded through the cliffs. Then we knew it was an earthquake.

5

Despite the precarious situation of the caves and the removal of many paintings by Le Coq and others, many paintings still remain at the site where today’s visitors can view them. Several other sites in the immediate vicinity of Kizil contain caves with paintings, such as those at Kumtura, which are the most extensive and well worth visiting.

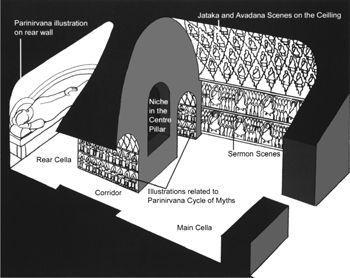

Many of the Kizil caves share the same structure: a room with a central stupa pillar for devotees to circumambulate. Since the time of the Buddha’s death, devotees expressed their devotion by walking clockwise around his buried remains in north India, and they circumambulated the stupas in the Western Regions as well. Unlike the stupas at Niya and Miran, the central pillars built along the Silk Road did not contain relics of the Buddha. Instead, a niche in the pillar originally held a statue of the Buddha, most of which are now missing.

Cave 38 at Kizil, dated to 400

CE

, is certainly one of the earliest and possibly the most visually appealing of all the caves.

6

The back wall of cave 38 shows the Buddha lying on his deathbed attended by the kings of different countries who came to offer their respects to him. Standing at the central pillar and looking back to the cave entrance, one views the Maitreya Buddha, the Buddha who presides over a future paradise, over the doorway.

Along the central spine of the arched ceiling of cave 38 are the Indian gods of the sun, moon, and wind, as well as two flaming buddhas and a two-headed Garuda, the legendary Indian bird who protects Buddhist law. Distinctly Indian in style, these were most likely painted by either artists from India or based on sketches brought from India. Le Coq calls the paintings “frescoes,” but because they were painted on dry plaster, they are not technically frescoes, a term reserved for paintings done on wet plaster. The cave construction techniques themselves came from India, adopted from the magnificent caves at Ajanta, outside Bombay, and other sites built by early Buddhists.

THE LAYOUT OF A TYPICAL KIZIL CAVE

Many caves at Kizil originally had the same structure. Visitors passed through an anteroom and entered the main room through a door. They demonstrated their devotion by walking around the central stupa pillar, which held a statue of the Buddha and was decorated with rocks and boughs of wood to represent Mount Sumeru, the mountain at the heart of the Buddhist cosmos. Often, only the holes that originally held these decorations are still visible. The back wall showed a painting of the Buddha on his deathbed. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

On each side of the central ridge of cave 38 are rows of diamond-shaped lozenges with postage-stamp edges fitting neatly into one another. The rows alternate

avadana

stories with

jataka

stories, which recounted the previous lives of the Buddha. Avadana stories, also called cause-and-effect stories, show a seated Buddha with a figure alongside; these allegorical tales about the Buddha taught listeners the relationship between their behavior in this life and its long-term effects in future lives.