The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent (22 page)

Read The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent Online

Authors: John Stoye

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire

During the day a fragment of brick or stone, dislodged by an enemy shot on the Löbel-bastion, hit Starhemberg on the head but he soon returned to work.

After dark the garrison tried its first sortie. The men were frightened, some turned back without leaving the shelter of the counterscarp although the others pushed forward. Casualties were few and the experiment was not discouraging, with a certain amount of damage done to the enemy works. It was therefore repeated more confidently twenty-four hours later. Nevertheless, by the morning of the 16th the Turks had already advanced so fast that they were only 200 paces from the salient angles of the counterscarp. Fortunately the preparations to resist them were also nearly complete. The Burg-gate, adjoining one side of the bastion, was being dismantled and the timber removed. A gallows was put up, as a warning to lawbreakers at a time of siege. The re-storage of powder continued. A new mill to make it was started in the moat itself. On the whole the defenders began to settle down, although depressed by the speed and scale of Turkish activity.

They had good reasons for their fears. Kara Mustafa began to carry out his next great move, a total encirclement of the city.

11

He went himself to survey the whole position, first from a point somewhere on the lower slopes of the Wiener Wald, and then from a suburb nearer the walls. He gave fresh orders to Hussein of Damascus, and to the Princes of Wallachia and Moldavia. In consequence, a strong force crossed the shallow waters of the Canal into Leopoldstadt and the islands. They drove back Lorraine’s rearguard under Schultz, which retreated towards the last of the Danube bridges. The Turks fired the buildings in Leopoldstadt and took up new positions in order to face Vienna from this side. Shortly afterwards they built bridges of their own,

above and below the city’s fortifications, to connect Leopoldstadt with the right bank of the river; they constructed various batteries and breastworks opposite the north wall held by Starhemberg’s men.

*

As a result, when the defenders had dismantled the bridge which in normal times linked the city and the suburb, Vienna was completely cut off and surrounded. Supplies coming downstream were barred by the Turkish bridge crossing the Canal to Rossau. A bombardment at close quarters from the north was inescapable. If they wished, the Turks could try an assault from this side while pressing towards the Hofburg from the south at the same time. It had also to be considered that if Thököly ever came up along the farther bank of the Danube, he would find it easier to reinforce the Turks for any action against the city; while the Turks could then assist him against Lorraine’s troops. A minor consolation for Starhemberg was that the ground rises fairly sharply from the bank of the Canal towards the centre of the town (as the Romans had noted centuries earlier, when they settled here), which made any attack from the north more difficult. Indeed, Kara Mustafa had already committed his main force to the approach from St Ulrich to the Burg; and throughout the siege the Turks never in fact tried to feint, or to mask their plans. The Grand Vezir was a bold and thoroughly unimaginative commander. As time passed Starhemberg must have realised this weakness in his opponent.

Kara Mustafa, on the Saturday, was able to visit Leopoldstadt. He siesta’d amid the ruined splendours of a Habsburg residence, the Favorita, and returned over the new bridge to Rossau. With the total encirclement of Vienna, the Turks were jubilant. They already spoke of a ‘final victory’ as something in the hollow of their hands. They felt the rhythm of their own triumphant advance; the batteries fired, the working-parties pushed forward the trenches and galleries, the guards took turn and turn about; while the musicians of the Grand Vezir, of the Aga of the Janissaries, and of all the pashas, began to play at every sunset and dawn.

Indeed the rhythm of a routine was quickly imposed on assailants and defenders alike, to be repeated daily for a week, until 22 July. It was felt in all the sectors into which the siege divided: behind the Turkish approaches, in the approaches themselves, along the counterscarp and moat and walls held by the garrison, behind the walls and in the streets of the city, and finally in Leopoldstadt. It affected somewhat less the Turkish detachment and the cavalry regiments of Lorraine which faced one another, at a considerable distance from Vienna, across the main stream of the Danube. Each of the sectors deserve attention, in order to grasp the complexity as well as the general pattern of these grim proceedings.

The initiative stemmed from Kara Mustafa. His headquarters were those splendid tents erected in the centre of the main Turkish encampment, and here

he lived in ostentatious luxury. He gave formal audiences, to the envoys of the Magyar lords Batthyány and Draskovich on 15 July,

*

or to the Aga who came direct from the Sultan on the 19th. Here also he honoured men with the robes which signified promotion in the Ottoman empire. Close by were the other centres of administration, judicial and financial. But of greater immediate significance was Kara Mustafa’s forward base, in the Trautson garden. It was set up in the shelter of the garden wall, a timber structure strengthened with sandbags. A little farther forward a hole was knocked through the wall, giving the Grand Vezir direct access to the trenches. As the days passed it seems as if more and more of his personal equipment was brought from the camp to the garden. From here he made his periodical tours of inspection in the Turkish trenches.

Christian surveyors who later examined the site gave unreserved praise to the layout and construction of these siege-works.

12

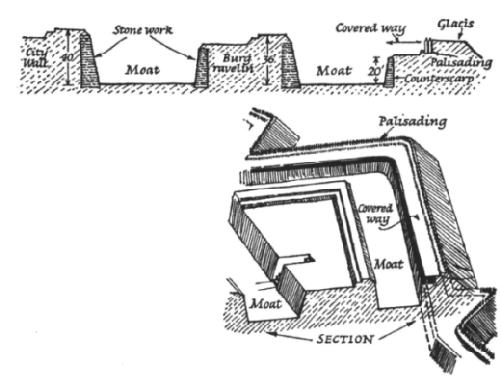

They found that, with all its appearance of bewildering elaboration, the system of approaches and parallels was admirably suited to the ground. Approaches led more or less directly across the glacis towards the three salient angles of the counterscarp in front of the Burg-bastion, the Burg-ravelin and the Löbel-bastion.

†

The Turks naturally describe the force aiming at the Burgbastion as their right flank; and here the approach began from the so-called Rakovitsch garden and was duplicated on each side, half-way along its course, by other trenches which proceeded in the same general direction. Parallels were thrown out to the left and right; on the extreme right, they were connected once more by another approach. This was one wing of the main Turkish front. Its parallels were linked with the system of approaches, even more elaborate, in the centre of the whole position. Here three main avenues, one of them coming direct from Kara Mustafa’s entrance by the Trautson garden, converged towards that part of the counterscarp opposite the Burg-ravelin. They were linked by a similar dense series of parallels, which extended towards the approaches on the left wing. One of the latter likewise began its course by branching off from Kara Mustafa’s main access to the central network; then, having gained sufficient ground to the left, it turned direct to the Löbel-bastion. Two more approaches followed the same course; one was the route which connected the parallels at their farthest extension on the left.

In the construction of this astonishing warren the Turks complained of the stoniness of the soil, but the corps of labourers worked (or were forced to work) extraordinarily well. They dug deep, and were therefore protected by high entrenchments as well as by the timber roofing inserted at many points. Much larger spaces were hollowed out at intervals in order to accommodate large bodies of troops. Batteries were installed and, when the system was

complete, more guns and timber and ammunition were brought right forward to the edge of the counterscarp. Sorties of the garrison were not only hampered by the soft earth thrown up in digging the trenches, but by the soldiers in the parallels, who protected the labourers as they pushed forward the various approaches.

An important but less effective part of the offensive was the artillery. It had started firing from the slopes behind the Trautson garden. Batteries were then mounted farther down and to the right, very near to where the approaches to the Burg-bastion began; then, below the Trautson gardens by the Rotenhof, as well as away to the left; then, closer and closer to the city. A cannonade was kept up intermittently throughout the siege, though it was apt to be silenced by rain. Its main defects, judged by the best standards of the period, were the lightness of the calibre and the poor quality of ammunition. There can be no reasonable doubt that Turkish artillery of the seventeenth century could not damage the stronger fortresses of Christian Europe with sufficient severity or speed. It has been suggested that the Ottoman officers did not bring their heaviest pieces with them, because the Sultan had originally agreed to have Györ besieged, or possibly Komárom, but not Vienna. More probably they never dreamt of transporting guns of the largest size across the Balkans, while they lacked the resources or expertise to have them manufactured at Buda, the obvious advanced base for all supplies. (From Buda, they actually received much of their very unsatisfactory gunpowder.) Turkish authorities distinguish between weapons of middle and heavy calibre, throwing balls from ten to forty

okka

13

in weight, and those of light to medium throwing balls between three and nine

okka.

Others were still lighter. At Vienna Kara Mustafa apparently had none of the heaviest type, reckoned essential for the effective battering of properly built defence-works from a reasonable distance; he had to use seventeen of the medium weights, and ninety-five lighter cannon. There were also no mortars available. In fact his artillery could slaughter men, but do no more than dint the fortifications. In spite of this the Ottoman commanders were convinced that the trench and the mine were the fundamental siege-weapons; gunfire was an auxiliary. For them, this had been the lesson taught by their ultimate success in taking Candia in Crete, in 1669.

The transformation of the glacis by a network of tunnels and trenches, the Turkish battle-front, had its counterpart in the defences of their opponents.

14

If it was earlier hoped to obstruct the Turks by burning down the suburbs and clearing the glacis, and this had failed because nothing seemed to halt their progress forward from St Ulrich, it became the more essential to convert the great moat into the most formidable barrier that men could contrive. First of all the Habsburg engineers turned their attention to the counterscarp again, reinforcing it with iron spikes, and with timber baulks set crosswise. At the salients, entrenchments were thrown up behind the area created by the angle, converting these vulnerable points into stockades of peculiar strength. The covered way along the counterscarp was sealed off into sections by building walls across it at intervals so that the attacker would be forced to take them one by one, after prolonged resistance in each. Behind this line of defence, and at a lower level, Starhemberg began to complicate the hazards on the floor of the moat. George Rimpler was his chief technical adviser here. More entrenchments were made, to connect the ravelins with the flanks of the bastions; half-way along such entrenchments block-houses were set up, projecting slightly forward, to enable their fire to command the ground in front of the ravelins. These defences were the so-called ‘caponnières’ of contemporary writings on this abstruse but practical subject. The engineers also paid particular attention to the Burg-ravelin itself, which faced the centre of the Turkish advance. Inside its walls more trenches were dug, and ramparts thrown up; the covered way connecting the ravelin with the main city-wall was strongly palisaded. One flaw in the original design of this ravelin worried the experts, but at this late stage it could hardly be remedied: a plinth projecting from the base of its outside wall, intended to prevent falling stone or earth from filling up the ditch, was too high and blocked a clear view of what might be going on at the foot of the wall. It proved a godsend to the miners of the enemy later on.

Lastly Starhemberg looked at the two bastions; he had to anticipate that these would in due course be exposed to powerful Turkish attacks.

*

His advisers were fairly satisfied with the Burg-bastion, except that it was ill-equipped with casemates for the purpose of counter-mining, and they contented themselves with throwing up inner works in the usual form of entrenchments and traverses. The Burg-gate was blocked. Then, along the foot of the curtain-wall running towards the Löbel-bastion, a secondary line of defence was constructed; at the point where it approached the Löbel itself an additional piece of work was hastily put in hand. This was an improvised extension of that bastion, designed to give more elbow-room to the defenders there, and to shorten the length of the curtain-wall, making this easier to protect. Even with these alterations there was still wretchedly little space on the Löbel-bastion for men or guns; and the lofty bulwark capping it, the ‘Katze’, remained very exposed to Turkish fire.

The defence was able to concentrate on this stretch between the Burg and the Löbel, because the enemy never made any serious attempt to test the garrison elsewhere. In a single ‘watch’ on 9 August (the only date for which there is a detailed list), out of a total of 2,193 officers and men at the twenty-two guard-posts round the city, over 1,000 held the line between Burg and Löbel.

15

Old maps show that elsewhere the counterscarp was reinforced by new works thrown out towards the glacis, but they seem never to have been used or needed. On the other hand, detachments of the garrison tried on 18 July to bring into the town some of the wood stacked outside the New-gate, but were not successful. The Turks, taking cover in the ruined buildings of Rossau immediately opposite, shot down the men who sallied out from the counterscarp.