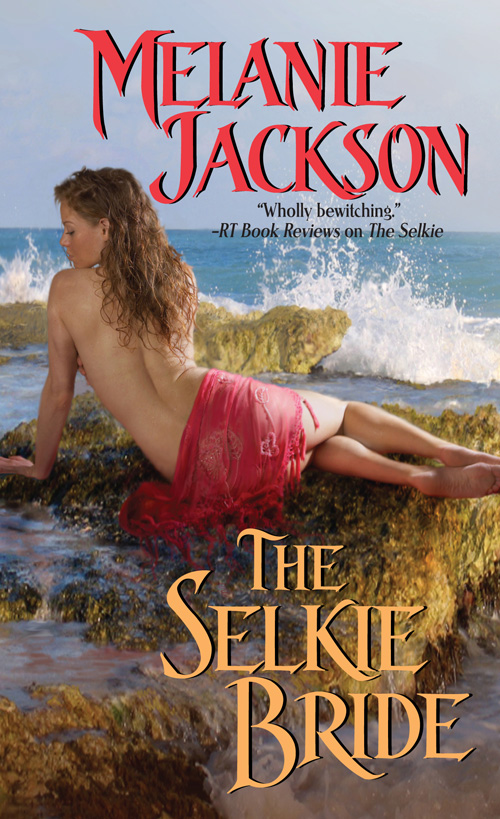

The Selkie Bride

Melanie Jackson

LOVE SPELL  NEW YORK CITY

NEW YORK CITY

Thunder crashed outside. The rain had grown ferocious while I read, and the wind all but screamed. It was a fit night out for neither man nor beast, so nothing could have surprised me more than to have my late reading interrupted by a pounding on the ancient cottage door. The blows were heavy and spaced evenly, like the tolling of a funeral bell. This was the sound of doom calling, and it demanded I answer.

I had a welcoming if insincere smile pasted in place when I pulled back the heavy bar and opened the door, but it faded quickly as I surveyed the creature on my doorstep. He was male—oh, definitely male—and quite the most beautiful being I had ever seen. But there was also something about him that seemed sinister and made me feel weak and insignificant as I stood before him. Perhaps it was the fierce black eyes or the alabaster skin, or the long hair that fell in a sleek cascade to below his shoulders. Or perhaps, most alarming of all, it was how not a drop of rain seemed to cling to him—not to his hair, not to his skin, not to his old fashioned sark and kilt.

For Auntie Nell and Uncle Ernie and all the happy childhood memories they gave me.

By all accounts my great-aunt, Megan Culbin, was always an eccentric woman. I never met her, so I can offer no firsthand impressions of the soundness of her mind. Certainly she had no high regard for my grandmother (an opinion for which I forgive her, since I also had no great liking for the woman; sorry, Mom). As for the truth of this narrative, I must confess to having some doubt. I am, in fact, all doubt. The story is a compelling one, though, so fictitious or not I present it here with only marginal editing and compiling and leave readers to decide what is or is not true, and whether Megan Culbin was deliberately misleading or simply insane.

The following collection of documents was purportedly received by Mr. Alexander Waverly of the firm of Waverly and Woolencott of Edinburgh in December of 1923. The solicitor claimed it came with an attached affidavit that it is in my aunt’s hand. Mr. Waverly’s grandson forwarded it to me on his death because I am my aunt’s only living female relative, and it took some decades to find me. Since there is no other money or property involved, I suspect the firm has been less than diligent in seeking me out and

Mr. Waverly may have felt that he was protecting my aunt’s reputation.

I present the whole collection now with no further comment.

Melanie Jackson

An American Woman’s Adventure in Scotland by Megan Culbin

Memory is faulty on its own, and mine has been interfered with to some degree, but I have rendered this account of the events of fall 1923 as honestly and accurately as possible. Any omissions are not intentional. Believe or don’t, but I’ve done all I can to make a record of my actions before I leave Findloss forever. Enclosed is a copy of my will, drawn in my own hand but not witnessed. We shall not meet again.

Many thanks, and all best wishes.

—Megan Culbin

From the journal of Megan Culbin

Somewhere in the Atlantic, aboard the good ship

Morgana

July 2, 1923

Where do dreams go when they die? In my case, they are headed for Scotland and I have high hopes of giving the nightmares a decent burial there. Maybe then the dead will rest in peace and I will live in the same.

To begin with, you must know that I did not love my husband. I hadn’t much liked Duncan when he was alive—not once we married and he revealed himself

fully for the crazed fiend he was—and I liked him only slightly better once he was dead and buried as far underground as the sexton could decently place him. The man made my life a bewildering nightmare of humiliation from the time we were married, but he did do one thing for which I was grateful: He actually got around to making a will in my favor before surrendering himself to complete drunkenness and debauchery. So, along with inheriting all his debts to angry tradesmen, I also gained title to his late Uncle Fergus Culbin’s cottage in Scotland, the mysterious and unmentioned old man having the consideration and forethought to die the week before my husband overdosed on absinthe and a seven-percent solution of cocaine while visiting a prostitute.

Thus I am on my way to Scotland, a widow of extremely modest means, and no kin to turn to except a puritanical aunt and uncle in Charleston and perhaps some distant relations of my late husband, who would doubtless prefer not to know me. My prospects are bleak enough, but I still count myself as the most fortunate of women. After all, I have escaped the worst possible marriage and will yet have a roof, however modest, over my head this winter. I am young and able-bodied. Whatever may yet come, not all widows—or wives—are so lucky.

Moan ye winds that never sleep, Howlye spirits of the deep…

—“

The Maiden of Morven”

October 31, 1923

“Did nowt scare you yonder noo?” a gruff voice asked, around the stump of a long pipe held clenched in yellowing teeth that I could see even at a distance.

“Weel, ’tis a feart place but I feel nae venom here. Nae ghosts. And still…” I heard the younger of the fishermen answer slowly.

It was a trick of the shifting wind that parts of their conversation would occasionally be blown to where I was sitting some yards away with my sketchbook, half hidden by the swaying marron grass. I was resting on what used to be the banks of an old river, whose course was marked by a thin line of aquatic grasses and gaunt, distorted trees where noisy bitterns lived. The water began at what once was Loch Findloss, a winter lake that dried up almost every summer but returned again in fall. Its course now remains forever dry, surrounded

by the remains of a wildwood that was prostrated by the wind during a horrific tempest and then fossilized in its surrendered posture. The village is likewise frozen. It has been this way since the Storm.

“Naeone ever carried the deid away for burial. They are either beneath the sand or taken by the sea. Either way, I doubt they rest easy here.”

The older fisherman spat and quickly looked about him. The nineteenth century lingers here, and the local custom is to never speak of those lost to the Storm if a bird or seal is near, lest they carry word back to the ocean and summon something unholy. He was safe that day; it was only me, the silent American, and a few fat hares eavesdropping on the conversation.

The fisherman’s opinion was a popular one, but I sincerely hoped that he was wrong about the ghosts, because this was now where I lived: Findloss, the cursed village. What I didn’t need were thoughts of the restless dead struggling out of the sand to keep me up nights; the restive winds and often nervous living were quite trial enough now that days were growing short and cold and the tide called uproariously night and day, temporarily thwarted from taking back the earth that had thrust itself out of the oceans, but never giving up entirely.

“Be it ever so humble,” I muttered, shaking sand from my skirts, an action that had grown so customary, I rarely marked it. The dunes around me were constantly shifting, and if one sat still for too long when the breeze was blowing the sand would bury one. All towns have their quirks and charms; ours was an ever-changing landscape—though I have to admit

that our whispering dunes possessed none of the appeal of the more famous singing sands of Eigg, and were in fact a great deal more sinister.

Findloss was and is a fishing village, granted official charter in 1411, though people lived here long before that in crude, windowless huts, and perhaps in caves before that. This is a fact listed in many books and also proved by the tax rolls the solicitor showed me while trying to dissuade me from moving here. It is also a well-documented reality that the village disappeared one Beltane night in 1845, buried under thirty feet of storm-driven sand, and for fifty years no taxes were collected because the village was missing. The rest of the stories about what happened here—and why, and caused by whom—are both conjecture and a source of endless discussion by the local fishermen and their brave spouses, the few souls who have reluctantly repopulated the area.

Everyone in the village and surrounding environs agrees that the original inhabitants of the cursed village did something terrible to bring tragedy on themselves. Most say that the villagers were greedy and made some deal with a pagan demon-god for rich fishing grounds and no storms, and that the annihilation of the village was God’s judgment upon them for their blasphemy. Another story says the villagers kidnapped some sea god’s daughter and held her hostage in exchange for fish and good weather. On the day that she escaped—or died—it is believed that her enraged father retaliated and sent the storm as punishment. Yet another story is that the secretly pagan villagers made annual human sacrifices to appease some sea monster,

and that one year the virgin tribute ran away rather than doing her duty, having predictable nasty consequences.

Whatever the case, much like the more famous Pompeii, Findloss was buried, destroyed in this instance by an angry storm driven by venomous west winds that washed over the village and smothered it in sand, where it was eerily preserved for five decades. Only two villagers survived this holocaust. Terrified by the inundation, most inhabitants fled to the church for sanctuary, but two men took flight in their boats and braved the gale. They alone lived to tell the tale, and spoke in a whisper about the Biblical-strength tempest that claimed their town. One of the men was Uncle Fergus’s father, a man called Iain Dubh, which is “Black John” in English.

I wonder sometimes why the wider world knows nothing of this terrible inundation, particularly when all of the British Isles are so proud to tell tales of their lost and sunken cities to gullible visitors. The damage must have been far-flung and economically devastating, not to mention the whole horrible fairy-tale quality to the event that made the story appealing; so why no legends about Findloss? I asked this of the solicitor after arriving in Scotland, and received a startling answer from a man I took to be educated and reasonably truthful. Fear, he said; atavistic dread so strong that people still won’t speak of it except in a whisper, because this storm was uncanny in ways that cannot be explained, even in terms of divine retribution. Couple that with the fact that it happened within the living memory of many local people, and you find an

extreme reluctance to speak of the shameful and terrifying matter.

Also, Findloss is “different.” It always has been. I soon discovered what the solicitor meant: peopled by witches and other wicked beings, who tend to be insular, keeping the outside world and its religious persecutions at bay. All murder was local.

I am not superstitious, but see the solicitor’s point now that I have lived here for a while. Six miles south of Findloss lies the town of Glen Ard, and four miles north is the village of Keil. Neither was disturbed by the wind or rain, or molested by the ocean on that fateful Beltane Eve. The inhabitants felt nothing and heard nothing of the storm that took their neighbors. Their skies were clear, the seas calm, and their celebration bonfires burned brightly. The wild-eyed survivors who arrived by boat at dawn were not at first believed when they appeared in Keil, relating their impossible tale of tempest and destruction, but investigation soon proved that they were right. Findloss had indeed disappeared in the night and been replaced with a desert wasteland where it would be found that almost nothing could grow. Of other survivors, if there were any, nothing was ever heard.

This is fairly standard fare as tales of disappearing cities go, and if the story ended there, it would be a site worthy of a visit by any intrepid visitor interested in exploring auld haunted Scotland. But that isn’t where the tale terminates. For fifty years Findloss lay buried, and the rocky waters nearby remained as shunned as the village’s shores, but on another Beltane Eve a half century later, a wind arose, this time from the east, and

in the morning the village reappeared. Houses, the kirk and churchyard, a small dead orchard and fishing boats—all were unburied, if apparently lifeless. It was a town for ghosts.

This was as disconcerting to the village’s neighbors as its disappearance had been. In many ways, even more so. If it was God’s wrath that took the village, shouldn’t that be a final judgment? Why had the town been returned to the light of day? Was it haunted?

Immediately following the resurrection, a party of intrepid and perhaps slightly inebriated fishermen armed with holy icons put in on the shore and went to investigate. Knowing the story of Findloss well, they walked first to the kirk, reasonably expecting it to still be filled with sand and many skeletons in need of burial. Instead they discovered the place scoured, swept clean by some supernatural broom that had carried away every last grain of sand and human bone. Every pew was in place. The water-damaged Bible was on the altar, open to Revelation.

There was more talk of curses and the influence of the Devil, but the alarmed fishermen bravely pressed on and found the entire village the same as the church: pristine and vacant, a ghostly place waiting for life to return. Since both nature and humanity abhor a vacuum, eventually it was re-inhabited. After all, as it says in Genesis:

If therefore any son of Adam comes and finds a place empty, he hath liberty to come and fill it and subdue the earth.

The kirk, however, was never re-consecrated, and so the sons of Adam in this locale are on their own when it comes to spiritual guidance. The village is stuck in uneasy status quo. Nothing old is

ever taken down; nor are the stones recycled for other purposes, lest the gods be offended. And nothing new is ever built, either. The town might as well still be imprisoned in sand, for all that it has changed since its rebirth.

I rather liked hearing the suggested stories of supernatural agency. I even began to collect them in my journal with an eye toward perhaps someday having them published. These dark fairy tales (I thought smugly on my arrival) were reassuring explanations for God-fearing folk who know that they will never personally have dealings with the Devil and therefore have nothing to dread from the Lord’s wrathful vengeance. I wasn’t able to believe in them myself, at least not at first. I think that I must be forgiven for this, in spite of all the warnings I received, both from the solicitor and from the villagers who would speak with me, for it is far easier for someone not raised with superstitious beliefs to suppose that the village disappeared due to some natural though freakish phenomenon rather than blaming it on magic and monsters.

Of course, because I did not believe the event happened due to some long-ago curse by a sea monster, I had the constant worry that another tempest might overtake the village at any time. The solicitor did nothing to reassure me on this score, and I found myself understandably fearful every time a storm arrived.

Findloss is only barely a village. It has taken decades to lure people back to it, and they come only because the fish are so abundant and the cottages there for the taking by any brave enough to dare the curse. There are no small children. Men with young families

do not come. Get the older fishermen drunk and they’ll claim the superior fishing is because the local sea god has relented on his curse or gone off to plague Norway. I myself suspected it due to the fact that the waters were unfished for fifty years and the creatures had a chance to breed unmolested and forgot to fear men. Not that I’ve said this out loud. I say very little out loud, just take notes on what I hear and smile politely. My late husband’s Uncle Fergus had not been liked, and was even suspected of sorcery by some of the weaker minds. I was viewed with a certain amount of superstitious awe for my willingness (as a defenseless female) to live in his cottage alone. Apparently Fergus Culbin was the last of the local line of Culbins, and it was widely believed that it was one of his godless ancestors, living in a now-ruined keep, that brought the curse down upon the village.

Twaddle, all of it. Nonetheless, Fergus was rumored able to dispense with his shadow when desired, a sure sign of diablerie—or a sign of a cloudy day, but that was less exciting to talk about late at night around the peat fires. And if the subject of Fergus’s wicked ways failed them, they could always talk about me. I had thought that I was leaving notoriety behind in the States, but such was not the case. However, the pity that had followed me after Duncan’s death had not made it here, so pride insisted the situation was an improvement. Better by far to be notorious than pitiful.

Though the idea of Fergus being a wizard was preposterous, there was enough anecdotal evidence of his moral turpitude in Findloss and Keil, especially in

regard to women, that I can readily believe he was a bad man who gave himself over, without reserve, to all forms of sin and vice. What a family I married into! My own husband had been given to nightmares and hallucinations, which I always blamed on drink but was now inclined to attribute in part to his upbringing. Who knew what memories and horrible ancestral tales pursued him even across the ocean and made him take refuge in opiates and strong spirits? It was enough to make one believe that the sins of the fathers really were visited on the children in the form of bad blood.

Need I say that if I had any other alternative—any chance of selling the cottage—I would have moved elsewhere? But I had no real options. Returning home to the scandal brought on by my husband’s death by overdose in a whore’s house was not to be borne, especially since I would be a poor relation suffered by my pious aunt and uncle only in the name of familial charity. And I hadn’t enough money to start over somewhere else. My meager inheritance from my parents had gone to pay Duncan’s gaming debts and my ticket for Scotland. My marketable skills were few: Before my marriage, I’d served as an unofficial amanuensis for an elderly lawyer, but he was dead and could not vouch for me. I had some proficiency at French and Latin and a smattering of Gaelic, a mild talent for drawing and storytelling, and minimal competence in the kitchen and with a needle, but that was it.

Of course I could remarry. As more than one person had put it, my face was my fortune. But I had turned my mind against this idea. Marriage had not suited

me the first time; I would not willingly enter into it again. That would be quite unfair to whomever I wedded. My corroded heart was still filled with uncharitableness and general distrust of men. Actually, of people in general. The undertaker, a longtime friend of my late father, didn’t know whether to send condolences or congratulations when Duncan died. Neither did my minister or my friends.

The latter hurt worst of all, though I understand what they were feeling. I was the first of my contemporaries to discover that eternal love could actually be perishable under the right, or wrong, circumstances. My situation frightened them and made them question—at least in a small way—the security of their own lives. They saw Duncan as a malignancy growing in the societal body and were relieved when he was excised. I, the shamed widow, became the living version of the cautionary tales told to young girls by their mothers. Who would wish to be reminded of such a thing, to live next door to it? Of course I became a pariah. At the end of the day, it was difficult to say which of my problems was most pressing, the financial or the emotional.