The Seer - eARC

Authors: Sonia Lyris

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-one

- Chapter Twenty-two

- Chapter Twenty-three

- Chapter Twenty-Four

- Chapter Twenty-five

- Chapter Twenty-six

- Chapter Twenty-seven

- Chapter Twenty-eight

- Chapter Twenty-nine

- Chapter Thirty

- Chapter Thirty-one

- Chapter Thirty-two

- Chapter Thirty-three

- Chapter Thirty-four

- Chapter Thirty-five

- Chapter Thirty-six

- Chapter Thirty-seven

- Chapter Thirty-eight

- Chapter Thirty-nine

- Chapter Forty

The Seer - eARC

Sonia Orin Lyris

Advance Reader Copy

Unproofed

ORIGINAL TRADE PAPERBACK! The debut of a stunning new talent. A poor, young woman rises to the heights of a crumbling empire, where she must speak hard truth to power in order to save a world from chaos.

Everybody Wants Answers. No One Wants the Truth.

The Arunkel empire has stood a thousand years, forged by wealth and conquest, but now rebellion is stirring on the borders and treachery brews in the palace halls. Elsewhere, in a remote mountain village, a young mother sells the prophesies of her sister, Amarta, in order to keep them and her infant child from starving. It's a dangerous game when such revelations draw suspicion and mistrust as often as they earn coin.

Yet Amarta's visions are true. And often not at

all

what the seeker wishes to hear.

Now in a tapestry of loyalty, intrigue, magic, and gold, Amarta has become the key to a ruler's ambitions. But is she nothing beyond a tool? As Amarta comes into her own as a seer, she realizes she must do more than predict the future. She must create it.

Baen Books

by Sonia Orin Lyris

The Seer

THE SEER

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2016 by Sonia Orin Lyris

A Baen Book

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

www.baen.com

ISBN: 978-1-4767-8126-6

Cover art by Sam Kenney

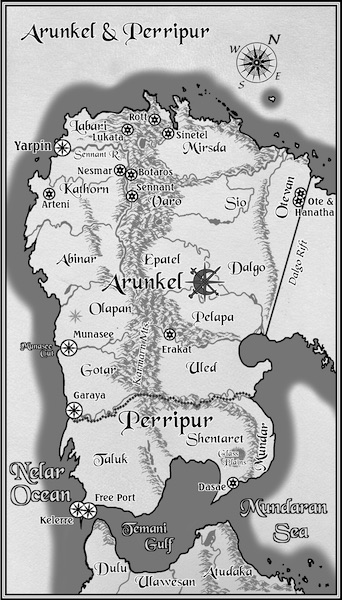

Map by Randy Asplund

First Baen printing, March 2016

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: t/k

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedication

For Devin

Chapter One

The tall man dropped five silver falcons onto the rough wooden table. The coins clinked against each other, silver faces bright in the light of the single candle that Dirina had just sparked to flame.

“I want answers,” he said.

Her hand went toward the coins as if of its own volition. She pulled it back, tucked it under the blanket wrapped tight around her shoulders.

If he wanted answers, he wanted Amarta, asleep with the baby in the small back room of the shack.

Her gaze went to the bright coins. Three were bird-side up; the king’s profile was on the other two. A good omen?

His large palm came down flat, covering the silver, breaking her focus. She looked up at his bearded face and met his dark eyes.

“Now.”

Now was moments after being woken by his pounding that shook the entire structure, dragging Dirina awake and off the cot where her sister and baby miraculously slept on.

Her gaze went to his hand, then back to his face, trying to make sense of this.

His expression told her nothing, but his cloak and coins and smell of horse said plenty. That her sister’s reputation had spread, again, far beyond this small mountain village to which they had come only last spring, before the baby was born. Where they were still welcome, if barely.

Were there really five falcons under his hand? Maybe she had imagined them.

She would tell him no. Come back tomorrow. When Amarta was rested. When Dirina could see him clearly in the daylight.

“Your pardon, ser,” she said, ducking her head. “She is asleep. She’s only a child. She—”

He picked up his hand, revealing the five coins again. For a moment her mouth moved silently.

“She’s only—”

“Asleep. A child. I heard you. Get her in here.”

Outside the wind picked up, blowing a roar through the trees, scraping branches against the roof, hissing through shutters that never closed properly, sneaking under the door that had to be bolted to stay shut in high winds.

Five falcons.

But Amarta was exhausted. She had foreseen three times today already. Next week’s weather, when the goat would birth, how many kids, the arrival of trade wagons. So, today, they had eaten.

Dirina liked eating. Feeding the baby from her own body always left her so very hungry. She always wanted more food.

Also, rent was due, the roof needed patching, and the stove ate peat voraciously.

Five falcons. She ached to touch them.

The candle flickered wildly in a puff of air. On the walls, shadows danced with the flame’s motion.

“I’m sorry, ser,” she said, pulling her hand back again. “She’s too tired. She can be ready in the morning. At first light. Then she would be happy to answer—”

Her breath caught at his look. He scared her, this large stranger whose face she couldn’t read, who had five falcons to spend on a child’s divination in the middle of the night.

Even his clothes were odd. Loose, as if he had so much material he didn’t know what to do with it. Some kind of wool, fine and thick. She wondered what it felt like.

He made a noise. Sharp, displeased. Taking hold of a nearby stool, he pulled it to the table and sat. It creaked a little.

“One of us is going to go back there and get her. She might prefer it be you.”

Dirina’s stomach tightened. She looked for the oak stick she kept in the corner, alarmed to not see it. There it was; it had slipped to the dirt floor. When she looked back at him, he was watching her.

This man had needed to bend to come inside. His loose clothes did not hide his bulk.

She should never have let him in.

Again his hand went for the falcons, and for a wretched moment she thought he might take them away. Instead he dropped another silver coin onto the pile.

Then another.

A beautiful, terrible sound.

“A moment,” Dirina said softly and ran to the tiny back room.

Through the shutter slats, pale moonlight illuminated a straw-stuffed cot where Amarta slept curled around the baby. Dirina had named him Pas, after a tasty fruit-filled pastry she had once eaten because every time she looked at him she felt as if she had bitten into something wonderful.

On her knees she reached over him, breathing a quick prayer that he would stay asleep. She squeezed her sister’s shoulder.

Amarta muttered something into the layers of clothes and blankets, the muffled, flat tone telling Dirina just how exhausted she was. Then she opened her eyes.

“Diri?”

“A man,” Dirina said. “He has seven falcons, Ama. Can you see for him?” She didn’t pause for an answer. “You must.” She brushed her sister’s dark hair out of her face. “Seven falcons. He won’t wait. My sweet, I’m sorry.”

Her sister struggled to sit up, blinking, then pulled a tunic over the light clothes she slept in and stood. Dirina hastily tucked the blankets around Pas and then followed Amarta into the other room.

Amarta looked at the man, at the coins on the table, then back at the man.

His eyebrows furrowed. “You are the seer?”

Dirina recognized the tone. It was easy to understand, with Amarta’s hair a dark, fluffy mess and her child’s eyes lidded with sleep.

Amarta nodded and sat across the table from him on another stool. Dirina stepped back, leaning against the wall by the stove, a grab away from the oak stick on the floor.

The man put his hands on the table and leaned forward a little. In the light of the candle, Dirina could make out odd white lines crossing the backs of his hands and fingers. Scars, she realized suddenly. They were all scars.

Amarta put a finger on the pile of silver coins.

“We don’t usually ask that much,” she said.

“Then do good work, girl.”

Her sister crossed her forearms on the table and lowered her chin atop them, squinting into the candle flame. Dirina gnawed a knuckle.

The silence lengthened. “Ama,” she said, summoning her most encouraging tone, “what do you see?” She gave the man a quick smile. “Sometimes she needs a moment.”

He tapped a fingernail on the table in a slow, annoying beat. “I don’t have a lot of moments.”

“Amarta?” She hadn’t fallen asleep, had she?

Those who came to them for answers were desperate, their problems having pushed them to spend money they didn’t have in the hope that someone else might know what was good for them better than they did. Usually she reminded her sister to say only good things to them. So often the future was not what people wanted it to be.

As the silence continued, her stomach went leaden, chest tightening. They needed this man happy with his answers.

The wind knocked a branch against the side of the house, and for a moment the candle flickered furiously, threatening to go out.

Then Amarta sat up, looking into the distance at something beyond flickering shadows and wood walls. Dirina knew the look, felt a flush of relief.

“There’s a man,” Amarta said easily. “He’s looking for you. And you—you’re looking for him, too. He’s your brother, isn’t he?”

The man nodded, very slowly, his attention now entirely on Amarta.

Dirina knew this look as well. No matter what people had heard about Amarta, no matter what they believed, this was the moment of shock, when she told them something she couldn’t possibly know.

“Where is he?” the man asked.

“One of you will be dead before sunrise,” Amarta said.

Dirina’s stomach clenched agonizingly. That was not the right thing to say. What was Amarta doing?

That times might be difficult. That people would need to be strong. That things would get better. Yes, all that. Not this, never this.

Because people rarely changed their actions, no matter what she told them, because that was how people were. Small things, like where and when to plant, that they might do, but big things, like not going to market next month, or insisting that someone leave and never come back, that was much harder.

Some things couldn’t be changed. Better not to speak of those things.

And yet the man did not look surprised.

“Where is he?” he asked.

“There’s a woman,” Amarta said. “She’s going to be very upset with whoever lives tonight.”

The man gave a humorless half-laugh. “He’ll be spared that, at least. Will her father keep his word this time?”

Amarta tilted her head back and forth in a gesture that spoke of scales that had nearly come even.

“I think yes. The spring after next, or the summer following. Then . . .” She nodded. “He will—I don’t know what it’s called. Give her the crown?”

Dirina heard her sister’s words but could not make sense of them.

“She will marry me,” the man said. Not quite a question.

Amarta nodded again. “If you live.”

“Where is he?” he demanded a third time, his voice strained.

Amarta glanced at the shuttered window.

“Not far. Four lanes to the north.”

The man stood up, fast, and there was a knife in his hand. The flash of metal caught Dirina’s gaze as surely as the coins had before. Her breath stopped in her throat.

“Tell me how to win against him.”

At this Amarta shook her head.

“Tell me,” he said in a tone so compelling Dirina ached to satisfy it herself with a reply.

“I don’t know,” Amarta answered.

“What do you mean, you don’t know?” he growled. “Look wherever it is you look and tell me.”

Amarta was breathing fast and shallow.

“It’s not clear. I can’t see it.”

The man tightened his grip on the knife, the tip pointing toward Amarta. Then, laying the knife on the wood, he rotated it, hilt toward her.

“Does this knife draw blood tonight?” he asked.

He was clever. Most people never understood that Amarta could answer the small questions easier than the big ones, or that touching an object could help foresee its future.

Amarta brushed the bronze and leather-wrapped hilt, tracing her fingers along the flat of the blade. She pulled back and shook her head.

His eyes narrowed. “Try again.”

“No,” she answered, her child’s voice unsteady but certain. “No blood on this blade tonight.”

He scowled. “If I wanted to, I could change that.” He took the knife again.

Amarta cringed away from the table. Dirina knelt down and picked up the oak stick.

“Tell me, girl,” he said, his voice full of threat. “Is there blood on this knife yet?”

Amarta’s shoulders shook. “No blood,” Amarta whispered.

Dirina thought frantically. She would throw herself at him. Get between him and Amarta.

But if she sacrificed herself, who would protect them then? What should she do?

“Put it down,” he said to Dirina, as if answering. “You don’t want to challenge me. You wouldn’t last two breaths.” His knife vanished beneath his cloak, hands empty again. “I don’t want your blood or hers. I said put it down.”

Dirina’s hands were trembling violently. The stick fell to the floor with a dull thud.

“Advise me,” he told Amarta. “What must I do to live through tomorrow’s sunrise?”

Once again Amarta was looking far away.

“Don’t hesitate. Because he will.”

The man followed Amarta’s gaze to the wall and slowly nodded. He stood, turned, and walked to the door, seeming to have already stepped into the future Amarta had seen. He paused, glanced back at them both.

“You had better be right, girl.”

He shut the door hard behind him, the walls shuddering with the force of it. Dirina hurried over and bolted it. Then she went to her sister.

“Ama?” After a moment her sister began to shake. Dirina held her until the ragged breaths turned calm, then pulled back, searching her sister’s brown eyes.

“Why did you say that? About killing and dying?”

“He paid us. We need the money.”

“But why him? Why not the brother?”

“He was here,” Amarta said, her voice cracking. “Was I wrong? I tried to see further, but I couldn’t.”

“My sweet. You can’t know everything.”

“It was too far away. All I could see was tonight. I’m sorry, Diri,” Amarta said, beginning to sob.

Dirina murmured reassurances, stroking her sister’s hair, swallowing her own growing unease.

A mistake to let him in, perhaps.

She had made so many mistakes, their difficult lives the consequence. Like forcing them to leave the village of their birth with nothing in hand. Or selling Amarta’s visions and needing to flee those who didn’t like the answers.

Like getting pregnant.

He was so beautiful, Pas’s father. She had known better but in the wanting had somehow ignored the knowing. He made her feel sweet and warm, put laughter into her bleak world, implying with every kiss that he would stay.

It had been a hard lesson to discover that he had gone. Harder still to discover that she was pregnant.

She loved the baby, fiercely, every finger and toe of him. But she should have known better.

Had

known better. Had been taught by her own mother to count the days of the moon, to mark time from blood. Her mother would be ashamed of her.

Except her mother was dead. And that, too, was Dirina’s fault.

There had been solutions to the pregnancy, but they couldn’t afford any of them. They couldn’t afford the baby, either, but there was no choice about that. So they went hungry.

And sold Amarta’s strange ability.

She hugged her sister close, the girl’s body tight.

“It’s over now, Ama. Let’s go back to bed and get warm.”

“No. He’s coming back.”

“What? Tonight?”

Amarta nodded.

Dirina bit back her next question. There were things it was better not to know.

Which was why she had not let Amarta see their parents’ broken bodies in the canyon, four years ago. She’d seen enough for both of them. She remembered her uncle’s hand tight on her arm. Yes, he would take them in, he said, words soft in her ear as his grip tightened, and all their parents had owned, but they had better be worth the trouble. He shook her for emphasis, holding her back from her parents’ bodies. An obligation, he said, watching her closely. Hard work. Did she understand?

She had not. Not then.

When he had let her go, Dirina fell to the ground, her arms around the still-warm bodies of their mother and father as she wept. Her uncle collected the baskets of rare crevasse honey her parents had harvested from nests along the high rock wall, where overhead, so many lengths above, ropes and pulleys had somehow failed.