The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (23 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

10

This family has played an important role in my life and has had a great influence on it; my parents before me had already undergone the influence of the personality of the Pitchot family. All of them were artists and possessed great gifts and an unerring taste. Ramon Pitchot was a painter, Ricardo a cellist, Luis a violinist, Maria a contralto who sang in opera. Pepito was, perhaps, the most artistic of all without, however, having cultivated any of the fine arts in particular. But it was he who created the house at Cadaques, and who had a unique sense of the garden and of life in general. Mercedes, too, was a Pitchot one hundred per cent, and she was possessed of a mystical and fanatical sense of the house. She married that great Spanish poet, Eduardo Marquina, who brought to the picturesque realism of this Catalonian family the Castillian note of austerity and of delicacy which was necessary for the climate of civilization of the Pitchot family to achieve its exact point of maturity.

11

This spot was objectively one of the richest properties in the country-side, and contained a large number of pictures painted by Senor R. Pitchot.

12

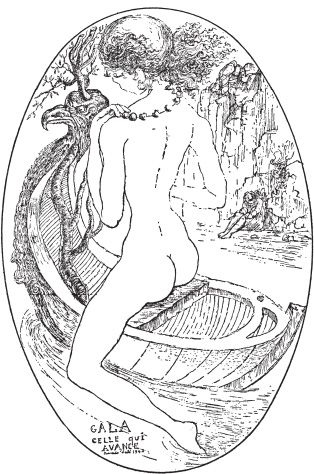

It is in this spot of the Muli de la Torre that most of my reveries during the whole rest of my life have taken place, especially those of an erotic character, which I wrote down in 1932; one of these having as protagonists Gala and Dullita was published in

Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution

. But the very special character of the text prevents including it in the present work.

13

The making of this kind of necklace is not a Dalinian invention as it seems, but on the contrary was a frequent game among the peasant children in the region where the Mulí de la Torre was located.

14

I learned much later that far from having the mortuary character which I attributed to it, this crown was a gift that had been offered as a tribute to Maria Gay at the Moscow Opera after one of her successes in the role of Bizet’s

Carmen

.

15

A farmer who witnessed one of these voluntary falls reported the event to Señor Pitchot. But no one would believe that I was able to jump thus without being killed. I became, indeed, extremely accomplished in high jumping. Later on in the gymnastics class of Figueras, I was to win the championship in high and broad jumping almost without effort. Still today I am a rather remarkable jumper.

16

The diabolo in my story assumed in every respect the substitutive role typical of sacrífices, and takes the place of Abraham’s sacrificial ram. In my case it symbolizes without euphemism the death of Dullíta, of Galuchka Rediviva, and also the possibility of their resurrection.

PART II

CHAPTER SIX

Adolescence Grasshopper Expulsion from School End of the European War

Adolescence is the birth of body hairs. In my case this phenomenon seemed to occur all at once, one summer morning, on the Bay of Rosas. I had been swimming naked with some other children, and I was drying myself in the sun. Suddenly, on looking at my body with my habitual narcissistic complacency, I saw some hairs unevenly covering the very white and delicate skin of my pubic parts. These hairs were very slender and widely scattered, though they had grown to their full length, and they rose in a straight line toward my navel. One of these, which was much longer than the rest, had grown on the very edge of my navel.

I took this hair between my thumb and forefinger and tried to pull it out. It resisted, painfully. I pulled harder and when I at last succeeded, I was able to contemplate and to marvel at the length of my hair.

How had it been able to grow without my realizing it on my adored body, so often observed that it seemed as though it could never hide any secret from me?

A sweet and imperceptible feeling of jealousy began to bud all around that hair. I looked at it against the sky, and brought it close to the rays of the sun; it then appeared as if gilded, edged with all the colors, just as when, half shutting my eyelids, I saw multitudes of rainbows form between the hairs of my gleaming eyelashes.

While my mind flew elsewhere, I began automatically to play a game of forming a little ring with my hair. This little ring had a tail which I formed by means of the two ends of the hair curled together into a single stem which I used to hold my ring. I then wet this ring, carefully introducing it into my mouth and taking it out with my saliva clinging to it like a transparent membrane and adapting itself perfectly to the empty circle of my ring, which thus resembled a lorgnette, with my pubic hair as the frame and my saliva as the crystal. Through my hair thus transformed I would look with delight at the beach and the distant landscape. From time to time I would play a different game.

With the hand which remained free I would take hold of another of my pubic hairs in such a way that the end of it could be used as the pricking point of a needle. Then I would slowly lower the ring with my saliva stretched across it till it touched the point of my pubic hair. The lorgnette would break, disappear and an infinitesimal drop would land with a splash on my belly.

I kept repeating this performance indefinitely, but the pleasure which I derived from the explosion of the fabric of my saliva stretched across the ring of my hair did not wear off–quite the contrary. For without knowing it the anxiety of my incipient adolescence had already caused me to explore obscurely the very enigma of the semblance of virginity in the accomplishment of this perforation of my transparent saliva in which, as we have just seen, shone all the summer sunlight.

My adolescence was marked by a conscious reinforcement of all myths, of all manias, of all my deficiencies, of all the gifts, the traits of genius and character adumbrated in my early childhood.

I did not want to correct myself in any way, I did not want to change; more and more I was swayed by the desire to impose and to exalt my manner of being by every means.

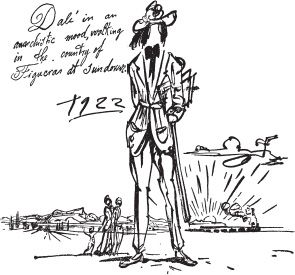

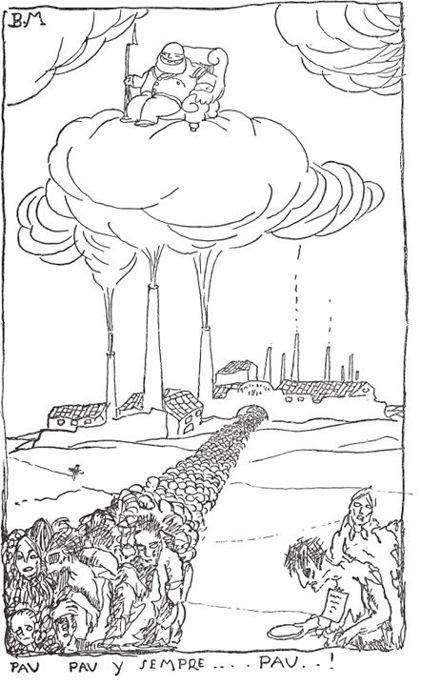

Instead of continuing to enjoy the stagnant water of my early narcissism, I canalized it; the growing, violent affirmation of my personality soon became sublimated in a new social content of action which, given the heterogeneous, well characterized tendencies of my mind, could not but be anti-social and anarchistic.

The Child-King became an anarchist. I was against everything, systematically and on principle. In my childhood I always did things “differently from others,” but almost without being aware of it. Now, having finally understood the exceptional and phenomenal side of my pattern of behavior I “did it on purpose.” It was only necessary for someone to say “black” to make me counter “white!” It was only necessary for someone to bow with respect to make me spit. My continual and ferocious need to feel myself “different” made me weep with rage if some coincidence should bring me even fortuitously into the same category as others. Before all and at whatever cost: myself—myself alone! Myself alone! Myself alone!

And in truth, in the shadow of the invisible flag on which these two words were ideally inscribed my adolescence constructed walls of anguish and systems of spiritual fortifications which for long years seemed to me impregnable and capable until my old age of protecting the sacred security of my solitude’s bloody frontiers.

I ran away from girls, for since the criminal memory of the Muli de la Torre, I felt in them the greatest danger for my soul, so vulnerable to the storms of passion. I made a plan, nevertheless, for being “uninterruptedly in love”; but this was organized with a total bad faith and a

refined jesuitical spirit that enabled me to avoid beforehand every material possibility of a real encounter with the beings whom I took as protagonists of my loves.

I always chose girls whom I had seen only once, in Barcelona or in

nearby towns, and whom it was doubtful or impossible that I should ever see again. The unreality of these beings, becoming accentuated with the fading of my recollections, made it easy to transmute my passion into new protagonists.

One of my greatest loves of this kind was born in the course of a traditional picnic in the country near Figueras. The little hills were sprinkled with clusters of people preparing their meals under the olive trees. Immediately I chose as the object of my love a young girl who was lighting a fire on the opposite hill. The distance that separated me from her was so great that I could not clearly make out her face; I knew already, however, that she was the incomparable and most beautiful being on earth. My love burned in my bosom, consuming my heart in a continual torment.

And each time a festival gathered together a multitude of people, I would imagine I caught glimpses of her in the milling throng.

This kind of apparition, in which doubt played the leading role, would come and cast fresh branches on the fire which the chimerical creature of my passion had lighted on the opposite hill-slope that first day when I had seen her from afar.

Loves of this kind, ever more unreal and unfulfilled, allowed my feelings to overflow from one girl’s image to another, even in the midst of the worst tempests of my soul, progressively strengthening my idea of continuity and reincarnation which had come to light for the first time in my encounter with my first Dullita. That is to say, I reached by degrees the conviction that I was really always in love with the same unique, obsessing feminine image, which merely multiplied itself and successively assumed different aspects, depending more and more on the all-powerful autocracy of my royal and anarchic will.

Just as it had been easy for me, since Señor Traite’s school, to repeat the experience of seeing “anything I wished” in the moisture stains on the vaults, and as I was able later to repeat this experience in the forms of the moving clouds of the summer storm at the Muli de la Torre, so even at the beginning of my adolescence this magic power of transforming the world beyond the limits of “visual images” burst through to the sentimental domains of my own life, so that I became master of that thaumaturgical faculty of being able at any moment and in any circumstance

always, always to see something else,

or on the other hand–what amounts to the same–“always to see the identical thing” in things that were different.

Galuchka, Dullita, second Dullita, Galuchka Rediviva, the fire-lighter, Galuchka’s Dullita Rediviva! Thus in the realm of sentiment, love was at the dictate of the police of my imagination!

I have said at the beginning of this chapter that the exasperated hyper-individualism which I displayed as a child became crystallized in my adolescence in the development of violently anti-social tendencies. These became manifest at the very beginning of my study for the baccalaureate,

and they took the form of “absolute dandyism,” based on a spirit of irrational mystification and systematic contradiction.