The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued His Empire (14 page)

Authors: Jack Weatherford

Genghis Khan left his Mongol nation rich and well protected.

Genghis Khan used sequences of spiritually meaningful numbers to organize his empire. Each number had a particular use: a social and cultural role in addition to its numerical value. Practical matters were organized in even numbers: two shafts of the cart or ten men to a military unit. Odd numbers held much greater supernatural power. Seven was to be avoided whenever possible, but nine and thirteen were the two most important numbers for him.

Genghis Khan’s father was named Yesugei, which meant “With Nines,” a name thought to bestow good fortune because its bearer would always be at the center of the eight directions and thus never be lost.

Mongols are often called by the name of the parent; thus Genghis Khan was “Son of Yesugei,” or “Son of Nines.” Mongols considered a name or title to carry a fate and a mission with it. Genghis Khan took his name and his patronymic seriously and literally. He structured life so that he was always the ninth, surrounded by eight. He had his primary group, known as Yesun Orlus, the “Nine Companions,” or the “Nine Paladins.” This set comprised the most talented and powerful men in the empire, including the four principal army commanders, known as the Four Dogs, plus the commands of his personal guard, known as the Four Horses. As always, Genghis Khan occupied the pivotal ninth position in the formation.

His personal guard originally consisted of eight hundred by day and eight hundred by night. After 1206 he adopted the older Turkic decimal system of organizing the lower military ranks into units of ten, building to the largest units of ten thousand. At this time he also increased his guard to ten thousand, but he arranged the army into eight units; the guard around him became the ninth.

In his arrangement of family government, he divided power and responsibility among eight of his children—four sons and four daughters. He had other sons and daughters, but he placed the future of the empire in the hands of these eight. Four sons held the steppes of the nomads, four daughters held the sedentary kingdoms, and Genghis Khan, the ninth in the system, ruled over them all. The system was simple, practical, and elegant. With the placement of four of his daughters as queens and four of his sons as khans, Genghis Khan had fulfilled the destiny bestowed upon him by his father’s name.

Genghis Khan, however, sought to surpass his father, and for this the number thirteen had a special, but largely secret, importance for him. In the formation of his nation in 1206, he organized the

khuriltai

, and thereby the empire, into thirteen camps, and he sometimes referred to his nation as the Thirteen Ordos, or Thirteen Hordes. His four dowager queens controlled the territory surrounding the mountain in the first circle, and then in the outer circle lay the territories of his four daughters and four sons. Thus in death, precisely as at the moment of creating his empire, Genghis Khan was in the center, the thirteenth position.

In the summer of 1229, two years after Genghis Khan’s death, all his offspring and the other officials of the Mongol Empire gathered to ratify Ogodei, the third son, as the Great Khan. The area of the 1206

khuriltai

now lay a little too close to Genghis Khan’s burial site on Mount Burkhan Khaldun, but the family still wanted to be near to the area. Ogodei chose an open steppe on the Kherlen River, a little to the south of the original

khuriltai

, near a spring where, according to oral tradition, his mother had nursed him, and possibly where he was born.

All the officials, generals, and Borijin clan members came. The daughters and the sons of Genghis Khan affirmed Ogodei, since their father had told them to do so. He had been chosen not because he was the smartest or the bravest, but because he was the most congenial to the largest number of people in the family, a situation created, at least in part, by his apparently being the heaviest drinker of all the heavy-drinking sons.

During the summer, as the family and officials gathered at Khodoe Aral, the supreme judge, the Tatar orphan raised by Mother Hoelun, began to write down the history of the Mongols. He gathered the stories and legends of the past, compiled the accounts of witnesses to the life of Genghis Khan, and wrote down his own memories. If he gave the record a title, it was lost, but it became known eventually as

The Secret History of the Mongols

.

At the end of the summer, Ogodei took his position at the geographic center of Mongolia, from where he would preside as the Great Khan over the eight kingdoms that constituted the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan. Despite the mediocrity of Ogodei’s leadership, the generals of Genghis Khan still commanded the army. With them in charge of the military campaigns, the empire continued to grow, adding Russia, Korea, and the Caucasus, and pushing ever deeper into China.

In terms of conquests and military expansion, the empire had not yet reached its zenith. Yet, paradoxically, it was already beginning to fall apart, and that collapse came from the center. The system left by Genghis Khan was too delicately balanced to survive. It began to totter even before all the delegates reached their homelands.

1242–1470

As the age declined, we fell into disorder,

abandoned our cities and retreated to the north

.

L

ETTER FROM A

M

ONGOL

K

HAN

TO THE KING OF

K

OREA, 1442

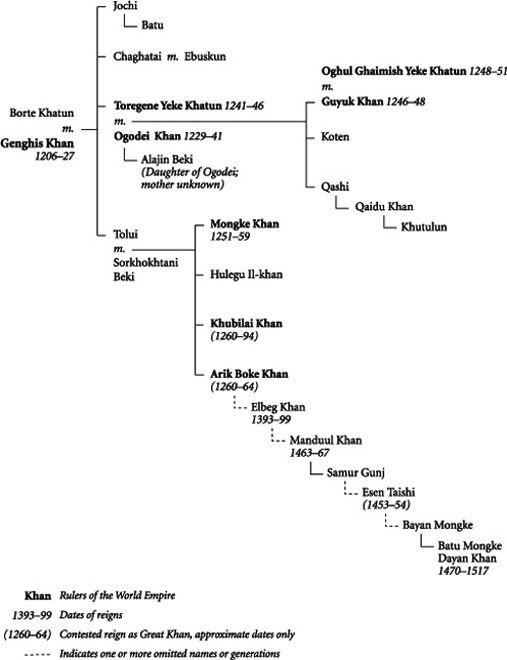

Rulers of the Mongol Empire

War Against Women

War Against WomenI

N THE FALL OF 1237, AFTER EIGHT YEARS IN OFFICE,

O

GODEI

K

HAN

ordered the most horrendous crime of his twelve-year reign and one of the worst Mongol atrocities recorded. The nearly unbearable horror was committed not against enemies, but against the nation’s daughters.

His soldiers assembled four thousand Oirat girls above the age of seven together with their male relatives on an open field. The soldiers separated out the girls from the noble families and hauled them to the front of the throng. They stripped the noble girls naked, and one by one the soldiers came forward to rape them. As one soldier finished with a screaming girl, another mounted her. “Their fathers, brothers, husbands, and relatives stood watching,” according to the Persian report, “no one daring to speak.” At the end of the day, two of the girls lay dead from the ordeal, and soldiers divvied out the survivors for later use.

A few of the girls who had not been raped were confiscated for the royal harem and then divided up in comically cruel ways—given to the keepers of the cheetahs and other wild beasts. The pride of Ogodei’s reign had been the international network of postal stations constructed across Eurasia. He decided to augment the services of the system by sending the less attractive girls to a life of sexual servitude, consigned to the string of caravan hostels across his empire to cater to the desires of passing merchants, caravan drivers, or anyone else who might want them. Finally, of the four thousand captured girls, those

deemed unfit for such service were left on the field for anybody present who wished to carry them away for whatever use could be found for them.

Somewhere in their wanderings the Mongols had learned the power of sexual terrorism. Muslim chroniclers charge that the Mongols had used a similar tactic only a few years earlier when Ogodei sent an army into North China. The Mongol force of 25,000 defeated a Chinese army of 100,000. The Mongol commander, according to the Muslims, permitted the mass sodomizing of the defeated soldiers. “Because they had jeered at the Mongols, speaking big words and expressing evil thoughts, it was commanded that they should commit the act of the people of Lot with all the Khitayans who had been taken prisoner.” Even if the account was exaggerated, its existence shows that people had the idea of using mass rape as a weapon.

Even in a world hardened by the suffering of a harsh environment and prolonged warfare, nothing like Ogodei’s transgression had been known to happen before, and nothing could excuse it. The chroniclers, long accustomed to reporting on rivers flowing with blood and massacres of whole cities, seem to choke on the very words they had to write to record the Rape of the Oirat Children. The Mongol chroniclers could only speak in vague terms that acknowledged a crime by Ogodei without admitting the horror of what the khan did to his own people.

The Persian chroniclers recorded the full cruelty and sheer evil behind the crime inflicted on these innocent, “star-like maidens, each of whom affected men’s hearts in a different way.” Everyone knew that this barbarous act violated in spirit and in detail the long list of laws Genghis Khan had made regarding women. Girls could be married at a young age but could not engage in sex until sixteen, and then they initiated the encounter with their husbands. They could not be seized, raped, kidnapped, bartered, or sold. Ogodei violated every single one of those laws.