The Second World War (30 page)

Early on the morning of 28 October, shortly before the meeting with Mussolini, Hitler was told that the Italian invasion of Greece had already begun. He was furious. He guessed that Mussolini was jealous of German influence in the Balkans and foresaw that the Italians might have a nasty surprise. Above all he feared that this move would draw British forces to Greece and provide them with a bombing base against the Ploesti oilfields in Romania. Mussolini’s irresponsibility might even put Operation Barbarossa at risk. But Hitler had mastered his anger by the time the

Sonderzug

halted alongside the platform in Florence where Mussolini awaited him. In the event, the two leaders’ discussion in the Palazzo Vecchio barely touched on the invasion of Greece, except for Hitler’s offer of an airlanding division and a parachute division to secure the island of Crete against a British occupation.

At 03.00 hours that day, the Italian ambassador in Athens had presented

an ultimatum to the Greek dictator, General Ioannis Metaxas, which was due to expire in three hours. Metaxas replied with a single ‘No’, but the Fascist regime was not interested in his refusal or compliance. The invasion, with 140,000 men, began two and a half hours later.

Italian troops advanced in a heavy downpour. They did not get far. It had already rained solidly for two days. Torrential streams and rivers washed away bridges and the Greeks, well aware of the attack which had been an open secret in Rome, blew up others. Unpaved roads became virtually impassable in the thick mud.

The Greeks

, uncertain whether the Bulgarians would also attack in the north-east, had to leave four divisions in eastern Macedonia and Thrace. Against the Italian attack from Albania, their line of defence ran from Lake Prespa on the Yugoslav border via the Grammos Mountains and then along the fast-flowing River Thyamis to the coast opposite the southern tip of Corfu. The Greeks lacked tanks and anti-tank guns. They had few modern aircraft. But their greatest strength lay in the universal outrage of their soldiers, determined to repel this attack by the despised

macaronides

, as they called them. Even the Greek community in Alexandria was caught up in the patriotic fervour. Some 14,000 sailed to Greece to fight, and the funds raised there for the war effort were greater than the whole of the Egyptian defence budget.

The Italians relaunched their offensive on 5 November, but they broke through only on the coast and north of Konitsa, where the Julia Division of the Alpini advanced over twenty kilometres. But the Julia, one of the finest Italian formations, was unsupported and soon found itself virtually surrounded. Only part of it escaped and General Prasca ordered his troops on to the defensive, along the 140-kilometre front. The Comando Supremo in Rome had to postpone the offensive in Egypt and divert troops to reinforce the army in Albania. Mussolini’s boast that he would occupy Greece in fifteen days was revealed as empty bombast, yet he still convinced himself that his forces would win. Hitler was unsurprised by this humiliation of his ally, having already predicted that the Greeks would prove better soldiers than the Italians. General Alexandros Papagos, the chief of the Greek general staff, was already bringing up his own reserves in preparation for a counter-attack.

Another blow to Italian pride took place on the night of 11 November, when the Royal Navy attacked the naval base of Taranto with Fairey Swordfish aircraft from the carrier HMS

Illustrious

and a squadron of four cruisers and four destroyers. Three Italian battleships, the

Littorio

, the

Cavour

and the

Duilio

, were hit with torpedoes for the loss of two Swordfish. The

Cavour

sank. Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, the commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean, could reassure himself

that he had little to fear from the Italian navy.

On 14 November, General Papagos launched his counter-offensive, secure in the knowledge that he had numerical superiority on the Albanian front until Italian reinforcements arrived. His men, with great bravery and stamina, began to advance. By the end of the year, the Greeks had forced their attackers back into Albania between fifty and seventy kilo metres from the frontier. Italian reinforcements, which brought their army in Albania up to 490,000 strong, made little difference. By the time of Hitler’s invasion of Greece the following April, the Italians had lost nearly 40,000 dead, and 114,000 casualties from wounds, sickness and frostbite. Italian claims to great-power status had been utterly destroyed. Any idea of a ‘parallel war’ was at an end. Mussolini was no longer Hitler’s ally, but his subordinate.

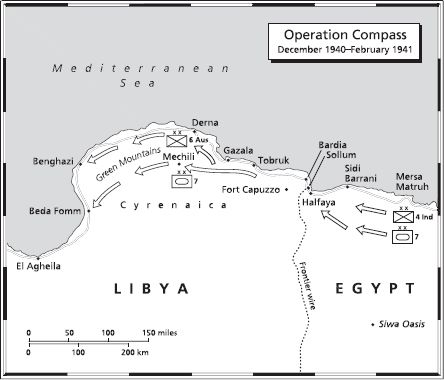

Italy’s chronic military weakness was soon evident in Egypt too. General Sir Archibald Wavell, the commander-in-chief Middle East, had a daunting array of responsibilities covering North Africa, East Africa and the Middle East as a whole. He had begun with only 36,000 men in Egypt facing 215,000 Italians in their Libyan army. To his south, the Duke of Aosta commanded a quarter of a million men, of whom many were locally raised troops. But British and Commonwealth forces soon began to arrive in Egypt to reinforce Wavell’s command.

Wavell, a taciturn and intelligent man who loved poetry, did not inspire Churchill’s confidence. The pugnacious prime minister wanted fire-eaters, especially in the Middle East where the Italians were vulnerable. Churchill was also impatient. He underestimated the ‘quartermaster’s nightmare’ of desert warfare. Wavell, who feared the prime minister’s interference in his planning, did not tell him that he was preparing a counter-attack, codenamed Operation Compass. He told Anthony Eden, then on a visit to Egypt, only when asked to send badly needed weapons to help the Greeks. Churchill, when he heard of Wavell’s plan on Eden’s return to London, claimed to have ‘

purred like six cats

’. He immediately urged Wavell to launch his attack as soon as possible, and certainly within the month.

The field commander of the Western Desert Force was Lieutenant General Richard O’Connor. A wiry and decisive little man, O’Connor had the 7th Armoured Division and the 4th Indian Division, which he deployed some forty kilometres south of the main Italian position at Sidi Barrani. A smaller detachment, Selby Force, took the coast road from Mersa Matruh to advance on Sidi Barrani from the west. Ships of the Royal Navy steamed along close to the coast ready to provide gunnery support. O’Connor had already concealed forward supply dumps.

Since the Italians were known to have many agents in Cairo, including in King Farouk’s entourage, secrecy was hard to maintain. So, to give the impression of having nothing on his mind, General Wavell, accompanied by his wife and daughters, went to the races at Gezira just before the battle. That evening he gave a party at the Turf Club.

When Operation Compass began early on 9 December, the British found that they had achieved complete surprise. The Indian Division, spearheaded by the Matilda tanks of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment, took the main Italian positions right up to the edge of Sidi Barrani in less than thirty-six hours. A detachment from the 7th Armoured Division, striking north-west, cut the coast road between Sidi Barrani and Buqbuq, while its main force attacked the Catanzaro Division in front of Buqbuq. The 4th Indian Division took Sidi Barrani by the end of 10 December, and four divisions of Italians in the area surrendered the next day. Buqbuq was also captured and the Catanzaro Division destroyed. Only the Cirene Division, forty kilometres to the south, managed to escape by pulling back rapidly towards the Halfaya Pass.

O’Connor’s troops had won a stunning victory. At a cost of 624 casualties, they had captured 38,300 prisoners, 237 guns and seventy-three tanks. O’Connor wanted to push on with the next phase, but he had to wait.

Most of the 4th Indian Division was transferred to the Sudan to face the Duke of Aosta’s forces in Abyssinia. As a replacement, he received the 16th Australian Infantry Brigade, the advance formation of the 6th Australian Division.

Bardia, a port just inside Libya, was the main objective. On Mussolini’s orders, Marshal Graziani concentrated six divisions around it. O’Connor’s infantry attacked on 3 January 1941, supported by their remaining Matildas. After three days, the Italians surrendered to the Australian 6th Division, and 45,000 men, 462 field guns and 129 tanks were captured. Their commander General Annibale Bergonzoli, known as ‘Electric Whiskers’ because of his startling facial hair, managed to escape westwards. The attackers had lost only 130 dead and 326 wounded.

Meanwhile the 7th Armoured Division had charged ahead to cut off Tobruk. Two Australian brigades hurried on from Bardia to complete the siege. Tobruk also surrendered, offering up another 25,000 prisoners, 208 guns, eighty-seven armoured vehicles and fourteen Italian army prostitutes who were sent back to a convent in Alexandria where they languished miserably for the rest of the war. O’Connor was horrified to hear that Churchill’s offer to Greece of ground forces as well as aircraft put the rest of his offensive at risk. Fortunately, Metaxas refused. He felt that anything less than nine divisions risked provoking the Germans without offering any hope of holding them off.

The collapse of the Italian Empire meanwhile continued in East Africa. On 19 January, with the 4th Indian Division ready in the Sudan, Major General William Platt’s force advanced against the isolated and unwieldy army of the Duke of Aosta in Abyssinia. Two days later the Emperor Haile Selassie returned to join in the liberation of his country, accompanied by Major Orde Wingate. And in the south, a force under Major General Alan Cunningham, the younger brother of the admiral, attacked from Kenya. Aosta’s army, crippled by a lack of supplies, could not resist for very long.

In Libya, O’Connor decided to go all out to trap the bulk of the Italian armies in the coastal bulge of Cyrenaica by sending the 7th Armoured Division straight across it to the Gulf of Sirte south of Benghazi. But many of its tanks were unserviceable, and the supply situation was desperate, with lines of communication stretching over 1,300 kilometres back to Cairo. O’Connor ordered the division to halt for the moment in front of a strong Italian position at Mechili, south of the Jebel Akhdar massif. But then armoured car patrols and RAF aircraft spotted signs of a major retreat. Marshal Graziani was starting to evacuate the whole of Cyrenaica.

On 4 February, the race which cavalry regiments called the ‘Benghazi

Handicap’ began in earnest. Led by the 11th Hussars, the 7th Armoured Division pushed across the inhospitable terrain to cut off the remains of the Italian Tenth Army before they could escape. The 6th Australian Division pursued the retreating forces round the coast, and entered Benghazi on 6 February.

On hearing that the Italians were evacuating Benghazi, Major General Michael Creagh of the 7th Armoured Division sent a flying column on ahead to cut them off at Beda Fomm. This force, the 11th Hussars, 2nd Battalion of the Rifle Brigade and three batteries of the Royal Horse Artillery, reached the road just in time. Facing 20,000 Italians desperate to escape, they feared that they would be overwhelmed by weight of numbers. But just as it looked as if they would be engulfed on the landward side, the light tanks of the 7th Hussars appeared. They charged the left flank of the Italian mass in line abreast, causing alarm and confusion. Fighting died down only as the sun set.

The battle recommenced after dawn as more Italian tanks arrived. But the British flying column also began to receive support as more squadrons caught up from the 7th Armoured Division. Over eighty Italian tanks were destroyed as they tried to break through. Meanwhile, the Australians advancing from Benghazi increased the pressure from behind. After a last attempt to escape had failed on the morning of 7 February, General Bergonzoli surrendered to Lieutenant Colonel John Combe of the 11th Hussars. ‘Electric Whiskers’ was the surviving senior officer of the Tenth Army.

Exhausted and miserable Italian soldiers sat en masse, huddled under the rain, as far as the eye could see. One of Combe’s subalterns, when asked over the radio how many prisoners the 11th Hussars had taken, is reputed to have answered with true cavalry insouciance: ‘Oh, several acres, I would think.’ Five days later, Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel landed in Tripoli, followed by the advance elements of what was to be known as the Afrika Korps.

MARCH–MAY 1941

O

nce Hitler saw that his attempts to defeat Britain had failed, he concentrated on the main objective of his lifetime. But before invading the Soviet Union he was determined to secure both his flanks. He began negotiations with Finland, but the Balkans in the south were more important. The oilfields of Ploesti would provide the fuel for his panzer divisions, while the Romanian army of Marshal Ion Antonescu would be a source of manpower. Since the Soviet Union also regarded south-eastern Europe as belonging to its sphere of influence, Hitler knew that he needed to act carefully to avoid provoking Stalin before he was ready.

Mussolini’s disastrous attack on Greece had achieved precisely what Hitler feared, a British military presence in south-eastern Europe. In April 1939, Britain had given Greece a guarantee of support, and General Metaxas had called for help accordingly. The British offered fighters–the first squadrons of the Royal Air Force crossed to Greece in the second week of November 1940–and British troops landed on Crete to free the Greek troops there for service on the Albanian front. Hitler, increasingly afraid that the British would use Greek airfields to attack the Ploesti oilfields, asked the Bulgarian government to set up early-warning observation posts along their border. But Metaxas insisted that the British should not attack the Ploesti oilwells, which would provoke Nazi Germany. His country could deal with the Italians, but not with the Wehrmacht.