The Second World War (143 page)

Traumatized German survivors from the front line ran back up the slope of the Seelow Heights, shouting ‘Der Iwan kommt!’ Further back, local farmers and their families also started to flee. ‘

Refugees hurry by

like creatures of the underworld,’ wrote a young soldier, ‘women, children and

old men surprised in their sleep, some only half-dressed. In their faces is despair and deadly fear. Crying children holding their mothers’ hands look out at the world’s destruction with shocked eyes.’

Zhukov in the command post on the Reitwein Spur became increasingly nervous as the morning progressed. Through his powerful binoculars he could see that the advance had slowed, if not halted. Knowing that Stalin would hand the Berlin objective to Konev if he failed to break through, he began cursing and swore at Chuikov, whose troops had still barely reached the edge of the flood plain. Zhukov threatened to strip commanders of their rank and send them to a

shtraf

company. He then suddenly decided to change his whole plan of attack.

In an attempt to speed up the advance, he would send Colonel General Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army in ahead of the infantry. Chuikov was horrified. He could imagine the chaos. At 15.00 hours, Zhukov put through a call to Stalin in Moscow and explained the situation. ‘

So, you’ve underestimated

the enemy on the Berlin axis,’ the Soviet leader said. ‘And I was thinking that you were already on the approaches to Berlin, yet you’re still on the Seelow Heights. Things have started more successfully for Konev,’ he added pointedly. Stalin did not comment on Zhukov’s proposed changes to his plan.

The change of plan caused exactly the sort of confusion Chuikov had feared. There were already massive jams, with the 1st Guards Tank Army trapped behind the vehicles of the other two armies, waiting to advance. It became a nightmare for traffic controllers trying to unscramble the mess. And even when the tanks were extricated and began to push forward, they were picked off by 88mm guns sited below Neuhardenberg. In the smoke, they found themselves ambushed by German infantry with Panzerfausts and a platoon of assault guns. Things did not improve when they finally began to climb the Seelow Heights. The mud on the steep slopes, churned by shellfire, often proved too much both for the heavy Stalin tanks and for the T-34s. On the left, Katukov’s leading brigade was ambushed by Tiger tanks of the SS Heavy Panzer Battalion 502. Only in the centre did they have any success where the 9th Fallschirmjäger Division collapsed. By nightfall, Zhukov’s armies had still failed to seize the crest of the Seelow Heights.

In the Führer bunker under the Reichschancellery, telephone calls were constantly being made to OKH headquarters out at Zossen demanding news. But Zossen itself, which lay to the south of Berlin, was vulnerable if Marshal Konev’s forces broke through.

The 1st Ukrainian Front, as Stalin had told Zhukov, was doing rather better, despite having had no bridgeheads across the Neisse. Konev’s

artillery and supporting aircraft kept the Germans deep in their trenches as the leading battalions rushed the river in assault boats. A wide smokescreen was also laid by the 2nd Air Army, aided by a gentle breeze in the right direction. It was impossible for the Fourth Panzer Army to identify where the attack was concentrated. Bridgeheads were established and soon tanks were ferried across while sappers began constructing pontoon bridges.

Konev did not suffer from Zhukov’s disastrous change of mind. He had already planned for the 3rd and 4th Guards Tank Armies to lead his offensive. Soon after midday, the first bridges were ready and their tanks rumbled across. While the Germans were still shaken from the bombardment and confused by the smokescreen, Konev sent his leading tank brigades straight through the German lines with orders not to stop. The infantry would mop up behind them.

That night of 16 April was a humiliating one for Zhukov. He had to call Stalin again on the radio-telephone to admit that his troops had not yet taken the Seelow Heights. Stalin told him that it was his fault for having changed the plan of attack. He then asked Zhukov whether he was sure he would secure the heights by the next day. Zhukov assured him that he would. He argued that it was easier to destroy the German forces in the open than in Berlin itself, so time would not be lost in the long run. Stalin then warned him that he would tell Konev to divert his two tank armies northwards towards the southern side of Berlin. He hung up abruptly. Soon afterwards he spoke to Konev. ‘

Zhukov is not getting on very well

,’ he said. ‘Turn Rybalko [3rd Guards Tank Army] and Lelyushenko [4th Guards Tank Army] towards Zehlendorf.’

Stalin’s choice of Zehlendorf was significant. It was the most southwestern suburb of Berlin and the closest to the American bridgehead across the Elbe. Perhaps it was also no coincidence that it adjoined Dahlem, with the nuclear research facilities of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. Three hours earlier, in response to an American request for information about the Soviet offensive against Berlin, General Antonov was instructed to reply that the Soviet forces were simply ‘

undertaking a large-scale reconnaissance

on the central sector of the front for the purpose of finding out details of the German defences’. The April Fool continued. Never before had a ‘reconnaissance’ been carried out by forces 2.5 million strong.

With Stalin’s support, Konev forced on his tank brigades to satisfy his ambition to beat his rival to the glorious prize. Zhukov was becoming frantic at the lack of progress. On the Seelow Heights the chaotic battle continued under clearer skies, which helped the Shturmovik fighter-bombers. The collapse of the 9th Fallschirmjäger Division, whose ranks

had been filled with Luftwaffe ground personnel rather than paratroopers, eased the situation for Katukov’s tank units but they still faced counterattacks, both by the

Kurmark

Division with Panther tanks and by soldiers and Hitler Youth fighting with Panzerfausts at close range.

Conditions in German dressing stations and field hospitals were gruesome. The surgeons were completely overwhelmed by the numbers of wounded. On the Soviet side, things were little better. Soldiers wounded on the first day had still not been collected and cared for, as reports revealed afterwards. The numbers rose all the time as the artillery of the 5th Shock Army began shelling Katukov’s tank brigades by mistake.

German aircraft of the Leonidas Squadron based at Jüterbog imitated the Japanese kamikaze pilots in mostly vain attempts to destroy the bridges over the Oder. This sort of suicide attack was termed a

Selbstopfereinsatz

–‘a self-sacrifice mission’. Thirty-five pilots died in this way. Their commander Generalmajor Robert Fuchs sent their names ‘to the Führer on his imminent fifty-sixth birthday’, assuming that it was the sort of present he would appreciate. But the insane scheme was soon halted by the advance of the 4th Guards Tank Army towards the squadron’s airfield.

Konev’s tank brigades raced for the River Spree south of Cottbus, in order to cross it before the Germans could organize any defence. General Rybalko, up with his lead brigade, did not want to waste time bringing up pontoon bridges. He simply ordered the first tank straight into the Spree, which was some fifty metres wide at that point. The water came to just above the tracks, but below the driver’s hatch. He drove on through, and the rest of the brigade followed in line ahead, ignoring the machine-gun bullets rattling against their armour. The Germans had no anti-tank guns in the area. The road to OKH headquarters in Zossen lay open.

Staff officers in Zossen had no idea of the breakthrough to the south. Their attention was still fixed on the Seelow Heights, where Generaloberst Gotthard Heinrici had thrown in his only reserve, Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner’s III SS

Germanische

Panzer Corps. This included the 11th SS Division

Nordland

manned by Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish and Estonian volunteers.

On the morning of 18 April, the fighting on the Seelow Heights reached a new intensity. Zhukov had heard from Stalin that Konev’s tank armies were forging ahead to Berlin, and that if his 1st Belorussian Front did not make better progress he would tell Rokossovsky to the north to turn his 2nd Belorussian Front towards Berlin as well. This was an empty threat since Rokossovsky’s forces had been so delayed that they did not cross the Oder until 20 April, but Zhukov was so desperate that he ordered attack after attack. Finally the breakthrough came later that morning. One of Katukov’s tank brigades charged through along the Reichsstrasse 1, the

main highway from Berlin which ran all the way to the now destroyed East Prussian capital of Königsberg. Generaloberst Theodor Busse’s Ninth Army was split, and disintegration soon followed. The cost had been high. The 1st Belorussian Front had lost more than 30,000 men killed, as opposed to 12,000 German soldiers. Zhukov showed little remorse. He was interested only in the objective.

That day, Konev was troubled only by an attack launched against the 52nd Army on his southern flank by Generalfeldmarschall Schörner’s forces. This was a hurried, ill-prepared operation and easily rebuffed. His two tank armies managed to advance between thirty-five and forty-five kilometres. He would have been even more encouraged if he had known of the chaos caused in Berlin as Nazi leaders interfered with those trying to organize the defence of the city.

Goebbels, the Reich defence commissar for Berlin, tried to act as a military commander. He ordered that all the Volkssturm units in the city should march out to create a new defence line. The commander of the Berlin garrison was appalled and protested. He did not know that secretly this was exactly what both Albert Speer and General Heinrici had wanted in order to avoid the destruction of the city. General Helmuth Weidling who commanded the LVI Panzer Corps was distracted by visits from Ribbentrop and Artur Axmann, the head of the Hitler Youth, who offered to send in more of his teenagers armed with Panzerfausts. Weidling tried to persuade him to desist from ‘

the sacrifice of children

for an already doomed cause’.

The approach of the Red Army increased the Nazi regime’s murderous instincts. Another thirty political prisoners were beheaded in Plötzensee Prison that day. SS patrols in the city centre did not arrest suspected deserters, but hanged them from lamp-posts with placards round their necks announcing their cowardice. Such accusations from the SS were hypocritical to say the least. While their patrols executed army deserters and even some Hitler Youth, Heinrich Himmler and senior officers of the Waffen-SS were secretly planning to disengage their units and pull them back to Denmark.

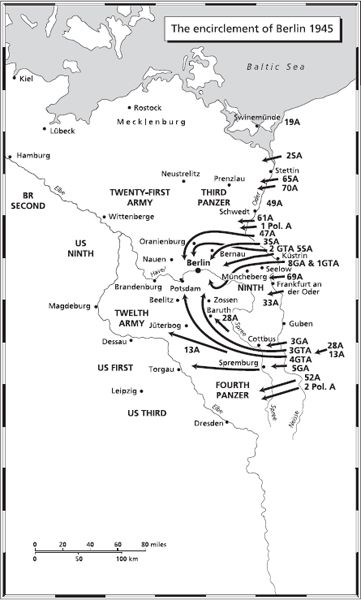

On 19 April the Ninth Army, irretrievably split in three, reeled back. Women and girls in the area, terrified of what awaited them, begged the soldiers to take them with them. The 1st Guards Tank Army supported by Chuikov’s 8th Guards Army reached Müncheberg in their advance along Reichsstrasse 1. While they headed for the eastern and south-eastern suburbs of Berlin, Zhukov’s other armies began to advance around the northern edge of the city. Stalin insisted on a full encirclement to ensure that no American attempt might be made to break through, even at the eleventh hour. American troops were entering Leipzig that day and took

Nuremberg after heavy fighting, but Simpson’s divisions on the Elbe remained where they were as Eisenhower had ordered.

The dawn of 20 April, Hitler’s birthday, followed the tradition of

Führerwetter

by providing a beautiful spring day. Allied air forces marked the day with their own greeting. Göring spent the morning supervising the evacuation of his looted paintings and other treasures from his ostentatious country house of Karinhall north of Berlin. After his possessions had been loaded on to Luftwaffe trucks, he pressed the plunger wired to the explosives planted inside. The house collapsed in a cloud of dust. He turned and walked to his car to be driven to the Reichschancellery, where along with the other Nazi leaders he would congratulate the Führer on what they all knew would be his last birthday.

Hitler looked at least two decades older than his fifty-six years. He was stooped and grey-faced and his left arm shook. That morning on the radio, Goebbels had called on all Germans to trust blindly in him. Yet it was clear to even his most devoted colleagues that the Führer was in no state to think rationally. Himmler, having drunk his leader’s health in champagne at midnight according to his private custom, was secretly trying to make contact with the Americans. He believed that Eisenhower would recognize that they needed him to maintain order in Germany.

The leaders who gathered in the half-wrecked grandeur of the Reichschancellery included Grossadmiral Dönitz, Ribbentrop, Speer, Kaltenbrunner and Generalfeldmarschall Keitel. It soon became apparent that only Goebbels intended to stay with his Führer in Berlin. Dönitz, who was given supreme command in northern Germany, was leaving with Hitler’s blessing. All the others were simply finding excuses to get out of Berlin before it was completely surrounded and its airfields seized by the Red Army. Hitler was disappointed in his supposedly loyal paladins, particularly Göring, who claimed that he would organize resistance in Bavaria. Several urged their Führer to leave for the south, but he refused. That day marked what became known as ‘the flight of the Golden Pheasants’, as senior Nazi Party members shed their brown, red and gold uniforms to escape Berlin with their families while routes to the south remained open.