The Second World War (111 page)

Roosevelt wanted to remind his subordinates that the Allies were not liberating France to install General de Gaulle in power. Most senior American officials were depressed by the President’s intransigence, and Churchill did his best to persuade him that they had to work with de Gaulle. But Roosevelt still wanted to impose a military government until elections were held, and insisted on creating an occupation currency. Banknotes were printed of such unconvincing appearance that the troops compared them to ‘cigar coupons’.

Roosevelt reluctantly agreed to Churchill issuing an invitation to de Gaulle to come to London, and two York aircraft were sent to Algiers to fly him and his staff back. At first de Gaulle refused to come because Roosevelt had rejected any discussion of French civil government. Duff Cooper, Churchill’s representative in Algiers, warned him that he would be playing into Roosevelt’s hands if he did not go to London. On 3 June the Comité Français de Libération Nationale in Algiers officially took the name of Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Française, and de Gaulle agreed at the very last moment to accompany Cooper to England.

South of Rome, Mark Clark’s dream was about to come true. An American infantry division had managed to slip through a gap in the Germans’ last line of defence and forced its collapse. Kesselring ordered an immediate withdrawal. Hitler allowed Rome to be declared an open city and did not order its destruction. This came not out of mercy or respect for ancient monuments and art, but because his attention was focused on the Channel and the thought that he would soon be able to destroy London with his flying bombs.

In Rome on 4 June, Mark Clark summoned his subordinate commanders for a briefing on the Campidoglio, having also assembled all the war correspondents in Italy. This photo-opportunity, with an exultant Clark holding a map and pointing north towards the retreating Germans, made his corps commanders cringe with embarrassment. But the Roman triumph of Marcus Aurelius Clarkus was short-lived. Soon after dawn on 6 June, a staff officer entered his suite in the Excelsior Hotel in Rome to wake him with the news of the Allied invasion of Normandy. ‘

How do you like that?

’ was Clark’s bitter reaction. ‘They didn’t even let us have the newspaper headlines for the fall of Rome for one day.’

Hitler eagerly awaited the invasion, convinced that it would be smashed on the Atlantic Wall. This would knock the British and Americans out of the war, and then he could concentrate all German forces against the Red Army. Generalfeldmarschall Rommel, whom he had put in charge of defending northern France, knew that the Atlantic Wall existed more in the realm of propaganda than in reality. His superior, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, regarded it simply as ‘

just a bit of cheap bluff

’.

After his experiences of Allied air power in North Africa, Rommel knew that bringing up reinforcements and supplies would be exceedingly diffi-cult. He had become embroiled in an argument with General der Panzertruppen Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg, the commander of Panzer Group West, and Guderian, now the inspector-general of panzer forces. They wanted to hold back the panzer divisions in forests north of Paris, ready for a massive counter-attack that would throw the Allies back into the sea, whether in Normandy or the Pas de Calais. But Rommel suspected that they would be decimated on their approach march by squadrons of Typhoon and P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers. He wanted the tanks deployed close to the possible landing sites.

Hitler, in his desire to maintain control through his policy of divide and rule, refused to have a unified command in France. As a result there was no supreme commander with authority over the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. Hitler even insisted that the bulk of the panzer divisions came directly under OKW control. They could not be moved without his express order. Rommel remained tireless in his efforts to improve the beach defences, especially in the Seventh Army’s sector of Normandy, where he became increasingly convinced that the attack would come. Hitler, on the other hand, kept changing his mind, perhaps partly to be able to claim later that he had predicted correctly. The Pas de Calais, defended by the Fifteenth Army, contained more of the V-weapon launch sites, it offered a shorter journey across the Channel and was much closer to fighter bases in Kent to provide air cover.

The German counter-intelligence services were certain that the invasion was near because of resistance activity and radio traffic, but the Kriegs-marine, studying the meteorological reports, concluded that there was no question of an invasion between 5 and 7 June because of bad weather. On the night of 5 June, they even cancelled all their own patrols in the Channel. Rommel, on being informed of this forecast, decided to visit his wife in Germany for her birthday and then visit Hitler at the Berghof to persuade him to release more panzer divisions.

The state of the weather was

Eisenhower’s

greatest worry during that first week of June. On 1 June, his chief meteorologist had suddenly warned him that the hot weather was about to end. The battleships of the

bombardment force were leaving Scapa Flow that very day. Everything had been timed for the invasion to start on the morning of 5 June. Weather reports were still so bad on 4 June that Eisenhower had to order a postponement. Fresh information soon showed that the weather might ease on the night of 5 June. While storms and heavy seas continued in the Channel, Eisenhower faced a terrible dilemma. Could he trust the accuracy of this forecast? General Miles Dempsey, who was to command the British Second Army in the invasion, considered Eisenhower’s decision ‘to go’ the bravest act of the war.

The tension eased as soon as Eisenhower had spoken and Montgomery agreed. It was the right decision. A further postponement would have pushed back the invasion by two weeks to accord with the next cycle of high tides. That would have had a disastrous effect on morale and probably lost the chance of surprise. A two-week delay would also have put the operation in the path of the worst storm the English Channel had seen in forty years. It is too easily assumed that Operation Overlord was bound to succeed, simply because of Allied air and naval supremacy.

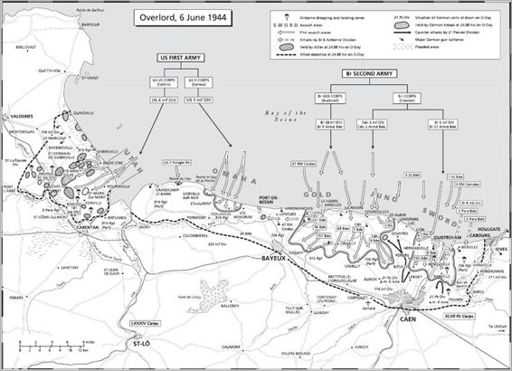

Early on the evening of 5 June, the French service of the BBC broadcast a series of coded messages to send the resistance into action. Heavily loaded paratroopers from the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions and the British 6th Airborne began to heave themselves into their aircraft and gliders. South of the Isle of Wight, the invasion convoys began to assemble with ships of every size, and landing ships of every sort. Soldiers crowded the rails to gaze in astonishment at the grey, choppy Channel filled with the vessels of a dozen nationalities in every direction, including 300 warships: battleships, monitors, cruisers, destroyers and corvettes.

Out ahead, a screen of 277 minesweepers advanced south in the gathering darkness towards the Normandy coast. Admiral Ramsay feared huge casualties among these wooden-hulled craft. Liberators and Sunderland flying-boats of Coastal Command continued to scour the seas from southern Ireland to the Bay of Biscay for U-boats. To Grossadmiral Dönitz’s great embarrassment, not a single German submarine reached the Channel to attack the invasion fleet.

The hundreds of transport aircraft carrying paratroopers and towing gliders curved out over the Channel to avoid flying over the invasion fleet and risking the disaster which happened during the invasion of Sicily. Even so, three C-47

Skytrains were shot down by Allied warships

after they had dropped their ‘sticks’ of American paratroopers on the Cotentin Peninsula.

The airborne drops did not go according to plan. Heavy anti-aircraft fire as the waves of transports crossed the coast caused formations to split up. Navigation was often faulty. Only a minority reached the correct drop

zones and many paratroopers had to trudge for miles to find their units. Others dropped on to German positions and were gunned down. Some fell into rivers and flooded marshes where, weighed down by all their equipment and trapped in their parachutes, they drowned. Yet the wild dispersion of drops had the unintended effect of confusing the Germans about the true targets of the operation, and this contributed to the impression that the attacks were part of a massive diversion in Normandy before the real attack came in the Pas de Calais. Only one operation, the seizure of Pegasus Bridge over the River Orue on the eastern flank, went spectacularly well. The glider pilots landed their craft in exactly the right position, and the objective was seized in a matter of minutes.

Before dawn on 6 June, almost every airfield in England began to throb with the sound of revving engines as squadrons of bombers, fighters and fighter-bombers began to take off to follow strictly marked corridors to avoid collision and clashes. Pilots and aircrew came from almost all Allied countries: Britain, America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Rhodesia, Poland, France, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Norway, the Netherlands and Denmark. Some squadrons, mainly of Halifaxes and Stirlings, had departed earlier on deception missions, dropping aluminium ‘Window’ and dummy paratroopers which exploded on landing.

The crews of the minesweepers and Admiral Ramsay could not believe their luck when, having accomplished their task, they turned back without a shot fired. The rough seas which had persuaded the Kriegsmarine to remain in port had proved their greatest blessing. They signalled good-luck messages to the destroyers which crept closer towards land, to take up their bombardment positions before first light. Cruisers and battleships anchored much further offshore.

The 130,000 troops crammed on the ships slept little that night. Some gambled, some tried to learn some French phrases, some thought of home, some wrote last letters, some read the Bible. Soon after 01.00 hours the troops, especially on US Navy ships, received generous breakfasts, then they began to put on their equipment which they continued to adjust out of nervousness while smoking compulsively. At around 04.00 hours troops were ordered to assemble on deck. To clamber down the scramble nets into the landing craft, which bucked and heaved alongside in the heavy swell, was a perilous undertaking, especially when so many men were overloaded with weapons and ammunition.

As soon as each landing craft was ready, its coxswain steered it away from the ship’s side to join a circling queue, following the little light on the stern of the one in front. A member of the 1st Infantry Division departing from the USS

Samuel Chase

described how ‘

the light would disappear

and

then reappear as we rose and fell with the waves’. Very soon men began to regret the munificence of their breakfast and were sick over the side, into their helmets or between their feet. The decks became slippery with vomit and seawater.

As a grey glow began to penetrate the overcast sky, the battleships opened up with their 14-inch main armament. Cruisers and destroyers immediately joined in. Generalleutnant Joseph Reichert of the 711th Infantry Division, watching from the coast, noted that ‘

the whole horizon

appeared to be a solid mass of flames’. By then there was enough dawn light for the Germans to see the size of the invasion fleet. Field telephones jangled furiously in command posts. Teleprinters chattered at Army Group B’s headquarters at La Roche-Guyon on the Seine, and in Rundstedt’s headquarters at Saint-Germain just outside Paris.

While the naval bombardment continued, landing craft filled with rocket launchers approached the shore, but most of their ordnance fell short in the water. The most frightening moment then came for the crews of the Duplex Drive Shermans, which began to flop off the front of landing craft into a sea which was far rougher than anything in which their tanks’ swimming abilities had been tested. In many cases, the upright canvas screen around the turret collapsed under the force of the waves and a number of tank crews went down trapped inside their vehicles.

On Utah Beach at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula, the US 4th Infantry Division landed with far fewer casualties than expected, and began to move inland to relieve the paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne. The long curving beach known as Omaha, dominated by bluffs covered in seagrass, proved an even deadlier objective than the Allies had expected. Much went wrong even before soldiers of the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions landed. The naval bombardment, although intense, had still been too short to be effective, and the bombing was a waste of time. Instead of following the line of the coast, which would have given aimers a better fix in the bad visibility, the US air commanders had insisted on coming in from the sea to avoid being shot at from the side. As they flew in over the landing craft, aircrew decided to wait a moment longer to avoid hitting their own men, so their loads dropped on to fields and villages inland. None of the beach defences, bunkers and fire points were touched. There were not even any craters on the beach in which the assaulting infantry could take cover. As a result the first wave suffered very heavy casualties, with enemy fire from machine guns and light artillery raking the landing craft as their ramps came down. Many landing craft became stuck on sandbars.