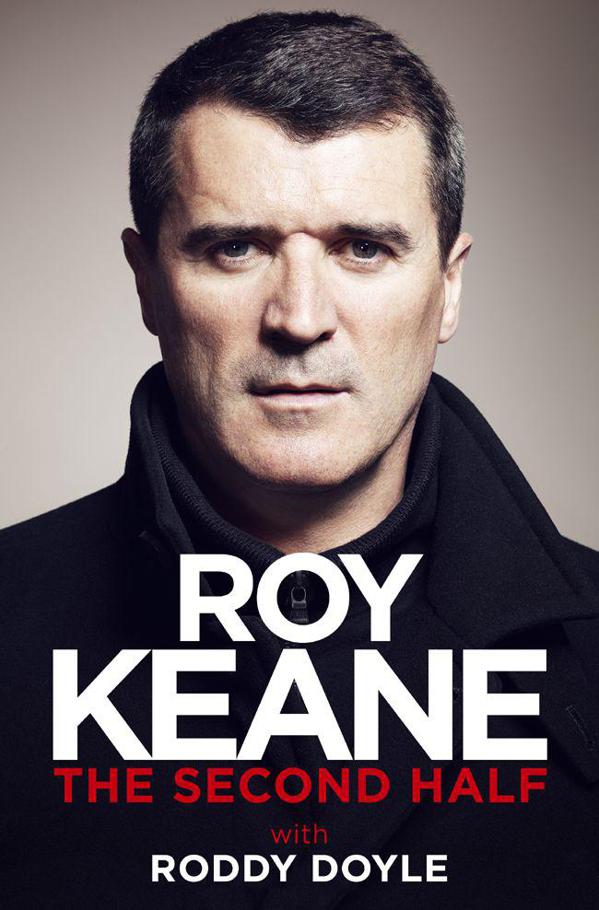

The Second Half

Authors: Roy Keane,Roddy Doyle

THE

SECOND

HALF

ROY

KEANE

with

RODDY DOYLE

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

LONDON

CONTENTS

Training with Carlos Queiroz, 2005. (John Peters/Manchester United/Getty)

Leaving Man United, November 2005. (Chris Coleman/Manchester United/Getty)

Signing for Celtic, 15 December 2005. (Ian Stewart/AFP/Getty)

Testimonial between United and Celtic at Old Trafford, 9 May 2006. (Laurence Griffiths/Getty)

I swapped sides at half-time. It was nice to be back. (Andrew Yates/AFP/Getty)

With Tony Loughlan at Sunderland v. West Brom, 28 August 2006. (Matthew Lewis/Getty)

Sunderland training. (Action/Lee Smith)

First match in charge of Sunderland, away to Derby, 9 September 2006. (Warren Little/Getty)

Celebrating Sunderland win at Luton, 6 May 2007. (Clive Rose/Getty)

Playing in the UNICEF charity match at Old Trafford in 2012. (Dave J. Hogan/Getty)

Ireland v. Turkey match, 25 May 2014. We’ll get it right, lads. (Jed Leicester Livepic/Action)

When you’re physically in trouble, it plays on your mind. You don’t get to a ball, and you tell yourself that you would have got it ten years ago, even though you mightn’t have. There’s a physical pain that you can put up with every day – but it’s what it does to your head. I still look back and wonder if I could have played for another year or two

.

‘Did I make the right decision?’

My wife reminds me, ‘Roy, do you not remember? You couldn’t even get out of your car.’

I could, but it would be torture. And getting out of bed. But I’d forget, because I loved the game so much. The carrot was always in front of me. I wanted to play for another year, and earn for another year

.

He told me how much he admired me. Like all the top lawyers, he was dead polite. I thought, ‘He’s nice, he’ll go easy on me.’

The popular version of the story is that I injured myself – I tore my anterior cruciate – when I went in for a tackle on Alfie Håland. Håland told me to get up and stop faking. So the next time I saw him, I did him. And I ended his career.

But that wasn’t what happened.

My book,

Keane

, came out in September 2002, just a few months after the World Cup and Saipan, and extracts from it were serialised in the

News of the World

. One of the extracts contained this passage from the book:

Another crap performance. They’re up for it. We’re not. City could have been ahead when Teddy stroked the penalty home with twenty minutes to go. Howey equalized five minutes from the end. I’d waited almost 180 minutes for Alfie, three years if you looked at it another way. Now he had the ball on the far touchline. Alfie was taking the piss. I’d waited long enough. I fucking hit him hard. The ball was there (I think). Take that, you cunt. And don’t ever stand over me

again sneering about fake injuries. And tell your pal Wetherall there’s some for him as well. I didn’t wait for Mr Elleray to show the card. I turned and walked to the dressing room.

That produced the headlines – it was great publicity. It was perfect in some ways, and I’m sure the publishers, Penguin, weren’t too upset, or the booksellers. I understand that when you publish a book you’re selling something; you’re selling part of yourself. But I didn’t anticipate the volume of the coverage. It was unbelievable; it was like I’d killed somebody. It was a nightmare at the time.

The book had been planned – the deadline and publication date – a year before. The idea was that it would finish after I’d played in the World Cup. It was supposed to be an upbeat book, on the back of qualification from a tough group and a good campaign in Japan. I think it was quite an upbeat book, but I didn’t play in the World Cup, and I couldn’t leave my house with my poor dog without being followed. That had gone on for a month or two, and it was just beginning to settle down. But now, the Håland tackle was the latest scandal. The media were all over it; they were running the show, demanding action. And, to be fair, I’d given them something to chew on.

The pressure was on the FA to do something about it, and they did. They charged me with bringing the game into disrepute, by committing a premeditated assault on Håland, and by profiting from my description of the tackle. The charges hurt me, particularly the second one – the idea that I’d almost bragged about deliberately injuring a player, in the hope of selling some extra books.

It was physically tiring. It was affecting my sleep, and my appetite. I was still preparing for games, but I was having problems with my hip. And it was emotionally tiring, too, coming so

soon after Saipan. My family, the ones closest to me, suffered. I was a footballer, but I was meeting lawyers.

The hearing took place in Bolton, at the Reebok. It wasn’t a court but it felt like a court. I think that was wrong. It was a footballing matter but it wasn’t being treated like a footballing matter. It was an FA charge, but I was travelling from Manchester in a car with a lawyer and a QC. That didn’t feel right. It was quiet in the car; I didn’t really know them. There was no positive energy, no ‘We’ll fight this’; it was all about damage limitation. It was a day at the office for them but it was a lot more than that for me. I knew I was going to lose. But I also knew, when I went home that night, it would be over.

Trying to get into the Reebok that day – you’d have thought I was up for murder.

I wish now I’d made my own way to the Reebok – ‘Listen, I’ll meet you there.’ Actually, I wish I hadn’t had a lawyer. I wish I’d gone in and just taken the punishment. The FA charged, and the FA delivered the verdict. Judge and jury. The pressure was on from the media. ‘They’ve got to do what’s right for the game.’ I’d been in situations before where I’d been cross-examined, and I’d felt that I’d been listened to. This time, almost immediately, I felt – ‘Just give me the fine.’ I never felt that I was getting my point across.

The FA had a murder lawyer. A big shot up from London. Jim Sturman. He was absolutely brilliant; he had me on toast. Jesus – for a tackle. He was a big Spurs fan, he told me. In the toilets, before the hearing. I was at the urinal beside him. We were talking, as two men in a toilet do.

He said, ‘I think you are a top player.’

He told me how much he admired me. Like all the top lawyers, he was dead polite.

I thought, ‘He’s nice, he’ll go easy on me.’

He ripped me to pieces – the fucker. It was his job, to rip me to pieces. I kept thinking, ‘I wish he was on my side.’

I was cross-examined for about an hour. He took out the book; he kept showing it to me.

‘This is you on the cover. This is your book, isn’t it?’

I said, ‘Yeah.’

‘This is your book, isn’t it?’

And I went, ‘Yeah.’

‘Do you stand by everything you said in the book?’

‘Yeah.’

‘So, whatever you said in this book—’

‘Yeah, but it was ghost-written.’

‘This is your book.’

He held it in front of me.

‘It’s supposed to be an honest book. You said these words.’

‘I didn’t mean it that way – I didn’t say it that way. I’m not sure I said all those words. I had a ghost writer.’

They were genuine arguments but I knew I was going to lose the fight. But you still have to fight. It’s like being in a boxing ring. You might be losing, but what are you going to do? You can’t drop your hands. You have to keep fighting.

He was very good. I remember thinking, ‘You fucker.’

His job was to present a picture of me as a thug, a head case, a man who goes out and injures his fellow professionals. And he did it – he succeeded.

The video helped.

‘Can we see the tackle?’

They had the tackle, in slow motion – my Jesus. You look at anything in slow motion, and it looks worse. Even blowing your nose looks dreadful in slow motion. The tackle in slow motion, from every angle – it looked bleak. I felt like saying, ‘Stop the fuckin’ video. Give me the fine and let’s move on.’

Jim Sturman had an easy day. I think he enjoyed it, as a Tottenham fan. The fucker.

I remember thinking, ‘I’m fucked here.’

I sat down.

It was Eamon Dunphy’s turn. Eamon was my ghost writer, and had come across from Ireland for the hearing, to be a witness. He’d already said that he’d used his own words to describe the tackle. Before we went in, I’d been going to say to him, ‘Eamon, if they ask you if you think I intentionally went to injure Håland, say no.’

But I decided not to; I wouldn’t embarrass him by saying something as simple as that.

Sturman asked him, ‘Mister Dunphy, do you think Mister Keane intentionally went to injure his fellow professional, Mister Håland?’

And Eamon’s three words back to Sturman were ‘Without a doubt.’

That was the case, my defence, out the window. Eamon had written the book; he was my witness. I think Eamon felt that

he

was on trial, and that it was almost a criminal court. He wanted to distance himself from it, and I could see his point of view. He’d delivered the book; he’d done his job. I’d approved it. I was on my own; it was my book, my name on it. But I think he might have thought that his account in the book was on trial; he just wanted to get it over with and get out of there. He was rushing for his flight back to Dublin.

I looked at him and thought, ‘I’m definitely fucked now.’

He didn’t go, ‘I think so’, or ‘Maybe’, even ‘Probably’, or ‘I can’t honestly give an answer to that.’

‘Without a doubt’ was what he said.

As the ghost writer, he was supposed to have been, I suppose,

in my mind, as he wrote the book. I’m not blaming Eamon – at all. But he didn’t help.

‘Without a doubt.’

I could tell from Jim Sturman’s expression, he was thinking, ‘Nice one.’

It was action; it was football. It was dog eat dog. I’ve kicked lots of players, and I know the difference between hurting somebody and injuring somebody. I didn’t go to injure Håland. When you play sport, you know how to injure somebody. That’s why you see people on the pitch getting upset when they see a certain type of tackle; they know what the intention behind the tackle was. I don’t think any player who played against me and who I’ve had battles with – Patrick Vieira, the Arsenal players, the Chelsea lads – I don’t think any of them would say anything too bad about me. They’d say that I was nasty, and that I liked a battle, but I don’t think any of them would say that I was underhanded. I could be wrong, of course. Maybe hundreds would say, ‘You fuckin’ were.’ I kicked people in tackles, but I never had to stand on the pitch and watch someone I’d tackled going off on a stretcher. I’m not saying that’s an achievement, but they always got up and continued playing.

There was no premeditation. My simple defence was, I’d played against Håland three or four times between the game against Leeds, in 1997, when I injured my cruciate, and the game when I tackled him, in 2001, when he was playing for Manchester City. I’d played against him earlier that season, and he’d had a go at Paul Scholes. If I’d been this madman out for revenge, why would I have waited years for the opportunity to injure him? I mightn’t have got that chance. Players come and go. My whole argument was, I’d played against him.

I’ve watched old games, where Håland is trying it on, booting

me. He was an absolute prick to play against. Niggling, sneaky. The incident took place in a match against City. But I’d played against him when he was at Leeds. The rivalry was massive between United and Leeds. Was I going around for years thinking, ‘I’m going to get him, I’m going to get him’?

No.

Was he at the back of my mind?

Of course, he was. Like Rob Lee was, like David Batty was, like Alan Shearer was, like Dennis Wise was, like Patrick Vieira was. All these players were at the back of my mind. ‘If I get a chance, I’m going to fuckin’ hit you.’ Of course I am. That’s the game. I played in central midfield. I wasn’t a little right-back or left-back, who can coast through his career without tackling anybody. Or a tricky winger who never gets injured. I played in the middle of the park.

There’s a difference between kicking somebody and injuring somebody. Any experienced player will tell you that.

Håland finished the game and played four days later, for Norway. A couple of years later he tried to claim that he’d had to retire because of the tackle. He was going to sue me. It was a bad tackle but he was still able to play four days later.

‘The ball was there (I think).’

I’m convinced that there were just two words that cost me. Those two words in brackets – ‘I think’ – left it open to interpretation that I went in on the man, and that I didn’t care if the ball was there or not, and that I’d been lying awake for years, waiting for Alfie Håland. I

knew

the ball was there. But he got there before me.

The two words in brackets cost me about four hundred grand.

It was a long day.

The decision – the verdict – was given that afternoon. There was talk of an appeal, but I think my solicitor, Michael Kennedy, used the word ‘closure’ – ‘We need closure on this, Roy’. It was a good way of describing it; I just wanted closure. I’d pay the fine, and the legal costs. They fined me £150,000, and my legal costs were over fifty. Throw the original fine in on top of that. I’d been fined two weeks’ wages by United when I’d made the tackle. I’d been given a four-match ban. Now the FA imposed another ban, five games. Double jeopardy. I had to sell a lot of books. But I was glad it was over. I think it was draining me, and my family.

I should have gone to the hearing without any lawyer, and taken my punishment. They were always going to find me guilty. There was a media scrum outside the front door. I was never going to walk out and go, ‘I got off.’

Do I regret what was in the book? Probably not, because I’d approved it before it was published. Did I focus on every word? Obviously not, because I don’t think I would have put in ‘(I think)’. Did I try to injure Håland? Definitely not. But I did want to nail him and let him know what was happening. I wanted to hurt him and stand over him and go, ‘Take that, you cunt.’ I don’t regret that. But I had no wish to injure him.

Yes, I was after him. I was after a lot of players, and players were after me. It’s the game. We have the great goals, the saves, the battles. But then there are parts of the game we don’t like – diving, cheating, the bad tackles. They’re part of the game. People want to avoid them, to pretend they’re not there. But there are players playing today who are after other players. Seamus McDonagh, the goalkeeping coach, has a great saying, advice that he gives to goalkeepers: ‘When you’re coming for crosses, come with violence.’ Nobody says it publicly. It’s not tiddlywinks we’re playing.

Håland pissed me off, shooting his mouth off. He’d tried to do me a couple of times when he was at Leeds. He’d come in behind me, quite happy to leave his mark on the back of my legs. There are things I regret in my life and he’s not one of them. He represents the parts of the game I don’t like.

Looking back at it now, I’m disappointed in the other Manchester City players. They didn’t jump in to defend their teammate. I know that if someone had done it to a United player, I’d have been right in there. They probably thought that he was a prick, too.

Everyone was telling me to move on, and I think I did move on. It had been a difficult few months. I was all about playing football. And this case had no redeeming features. Michael said, ‘We need closure’, and that worked for me. I believe that if you do something wrong you should take your medicine. I never felt that I was the innocent victim. I should never have spent my money on lawyers. I should have just said, ‘That was what happened. I didn’t mean it that way – but, obviously, it’s in the book.’

I thought it was about survival, making the damage as small as possible. I wondered why I was there – a bit. I wondered why I had a lawyer. This wasn’t about winning or losing, or right and wrong, innocence or guilt. It was about damage limitation. I might have come out happier if the fine had been less. But the size of the fine didn’t surprise me. The pressure was there, to punish me. The legal and logical arguments were never going to work: I had a ghost writer who put his own style across; they were Eamon’s words; I’d already been punished; my right to free speech.