The Sarantine Mosaic (2 page)

Read The Sarantine Mosaic Online

Authors: Guy Gavriel Kay

âChronicle of the Journey of Vladimir, Grand

Prince of Kiev, to Constantinople

PROLOGUE

Â

T

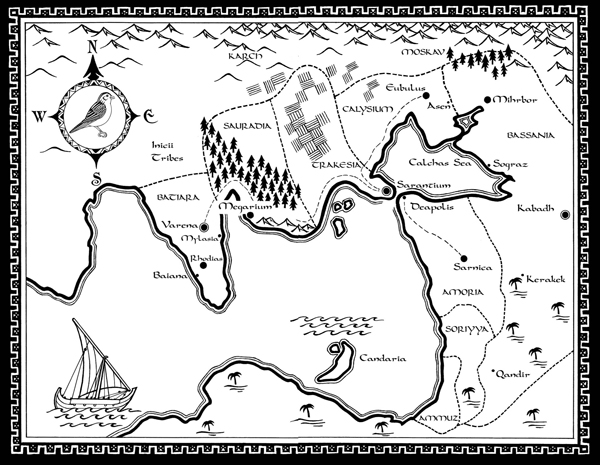

hunderstorms were common in Sarantium on midsummer nights, sufficiently so to make plausible the oft-repeated tale that the Emperor Apius passed to the god in the midst of a towering storm, with lightning flashing and rolls of thunder besieging the Holy City. Even Pertennius of Eubulus, writing only twenty years after, told the story this way, adding a statue of the Emperor toppling before the bronze gates to the Imperial Precinct and an oak tree split asunder just outside the landward walls. Writers of history often seek the dramatic over the truth. It is a failing of the profession.

In fact, on the night Apius breathed his last in the Porphyry Room of the Attenine Palace there was no rain in the City. An occasional flash of lightning had been seen and one or two growls of thunder heard earlier in the evening, well north of Sarantium, towards the grainlands of Trakesia. Given the events that followed, that northern direction might have been seen as portent enough.

The Emperor had no living sons, and his three nephews had rather spectacularly failed a test of their worthiness less than a year before and had suffered appropriate consequences. There was, as a result, no Emperor Designate in Sarantium when Apius heardâor did not hearâas the last words of his long life, the inward

voice of the god saying to him alone, â

Uncrown, the Lord of Emperors awaits you now.

'

The three men who entered the Porphyry Room in the still-cool hour before dawn were each acutely aware of a dangerously unstable situation. Gesius the eunuch, Chancellor of the Imperial Court, pressed his long, thin fingers together piously, and then knelt stiffly to kiss the dead Emperor's bare feet. So, too, after him, did Adrastus, Master of Offices, who commanded the civil service and administration, and Valerius, Count of the Excubitors, the Imperial Guard.

âThe Senate must be summoned,' murmured Gesius in his papery voice. âThey will go into session immediately.'

âImmediately,' agreed Adrastus, fastidiously straightening the collar of his ankle-length tunic as he rose. âAnd the Patriarch must begin the Rites of Mourning.'

âOrder,' said Valerius in soldier's tones, âwill be preserved in the City. I undertake as much.'

The other two looked at him. âOf course,' said Adrastus, delicately. He smoothed his neat beard. Preserving order was the only reason Valerius had for being in the room just now, one of the first to learn the lamentable situation. His remarks were ⦠a shade emphatic.

The army was primarily east and north at the time, a large element near Eubulus on the current Bassanid border, and another, mostly mercenaries, defending the open spaces of Trakesia from the barbarian incursions of the Karchites and the Vrachae, both of whom had been quiescent of late. The strategos of either military contingent could become a decisive factorâor an Emperorâ if the Senate delayed.

The Senate was an ineffectual, dithering body of frightened men. It was likely to delay unless given extremely clear guidance. This, too, the three officials in the room with the dead man knew very well.

âI shall,' said Gesius casually, âmake arrangements to have the noble families apprised. They will want to pay their respects.'

âNaturally,' said Adrastus. âEspecially the Daleinoi. I understand Flavius Daleinus returned to the City only two days ago.'

The eunuch was too experienced a man to actually flush.

Valerius had already turned for the doorway. âDeal with the nobility as you see fit,' he said over his shoulder. âBut there are five hundred thousand people in the City who will fear the wrath of Holy Jad descending upon a leaderless Empire when they hear of this death. They are my concern. I will send word to the Urban Prefect to ready his own men. Be thankful there was no thunderstorm in the night.'

He left the room, hard-striding on the mosaic floors, burly-shouldered, still vigorous in his sixtieth year. The other two looked at each other. Adrastus broke the shared gaze, glancing away at the dead man in the magnificent bed, and at the jewelled bird on its silver bough beside that bed. Neither man spoke.

Outside the Attenine Palace, Valerius paused in the gardens of the Imperial Precinct only long enough to spit into the bushes and note that it was still some time before the sunrise invocation. The white moon was over the water. The dawn wind was west; he could hear the sea, smell salt on the breeze amid the scent of summer flowers and cedars.

He walked away from the water under the late stars, past a jumble of palaces and civil service buildings, three small chapels, the Imperial Silk Guild's hall and workspaces, the playing fields, the goldsmiths' workshops, and the absurdly ornate Baths of Marisian, towards the Excubitors' barracks near the bronze gates that led out to the City.

Young Leontes was waiting outside. Valerius gave the man precise instructions, memorized carefully some time ago in preparation for this day.

His prefect withdrew into the barracks and Valerius heard, a moment later, the sounds of the Excubitorsâ his men for the last ten yearsâreadying themselves. He drew a deep breath, aware that his heart was pounding, aware of how important it was to conceal any such intensities. He reminded himself to send a man running to inform Petrus, outside the Imperial Precinct, that Jad's Holy Emperor Apius was dead, that the great game had begun. He offered silent thanks to the god that his own sister-son was a better man, by so very much, than Apius's three nephews.

He saw Leontes and the Excubitors emerging from the barracks into the shadows of the pre-dawn hour. His features were impassive, a soldier's.

It was to be a race day at the Hippodrome, and Astorgus of the Blues had won the last four races run at the previous meeting. Fotius the sandalmaker had wagered money he couldn't afford to lose that the Blues' principal charioteer would win the first three races today, making a lucky seven in a row. Fotius had dreamt of the number twelve the night before, and three quadriga races meant Astorgus would drive twelve horses, and when the one and the two of twelve were added together ⦠why, they made a three again! If he hadn't seen a ghost on the roof of the colonnade across from his shop yesterday afternoon, Fotius would have felt entirely sure of his wager.

He had left his wife and son sleeping in their apartment above the shop and made his way cautiouslyâthe streets of the City were dangerous at night, as he had

cause to knowâtowards the Hippodrome. It was long before sunrise; the white moon, waning, was west towards the sea, floating above the towers and domes of the Imperial Precinct. Fotius couldn't afford to pay for a seat every time he came to the racing, let alone one in the shaded parts of the stands. Only ten thousand places were offered free to citizens on a race day. Those who couldn't buy, waited.

Two or three thousand others were already in the open square when he arrived under the looming dark masonry of the Hippodrome. Just being here excited Fotius, driving away a lingering sleepiness. He hastily took a blue tunic from his satchel and pulled it on in exchange for his ordinary brown one, modesty preserved by darkness and speed. He joined a group of others similarly clad. He had made this one concession to his wife after a beating by Green partisans two years before during a particularly wild summer season: he wore unobtrusive garb until he reached the relative safety of his fellow Blues. He greeted some of the others by name and was welcomed cheerfully. Someone passed him a cup of cheap wine and he took a drink and passed it along.

A tipster walked by selling a list of the day's races and his predictions. Fotius couldn't read, so he wasn't tempted, though he saw others handing over two copper folles for a sheet. Out in the middle of the Hippodrome Forum a Holy Fool, half naked and stinking, had staked a place and was already haranguing the crowd about the evils of racing. The man had a good voice and offered some entertainment ⦠if you didn't stand downwind. Street vendors were already selling figs and Candaria melons and grilled lamb. Fotius had packed himself a wedge of cheese and some of the bread ration from the day before. He was too excited to be hungry, in any case.

Not far away, near their own entrance, the Greens were clustered in similar numbers. Fotius didn't see Pappio the glassblower among them, but he knew he'd be there. He'd made his bet with Pappio. As dawn approached, Fotius beganâas usualâto wonder if he'd been reckless with his wager. That spirit he'd seen, in broad daylight â¦

It was a mild night for summer, with a sea wind. It would be very hot later, when the racing began. The public baths would be crowded at the midday interval, and the taverns.

Fotius, still thinking about his wager, wondered if he ought to have stopped at a cemetery on the way with a curse-tablet against the principal Green charioteer, Scortius. It was the boy, Scortius, who was likeliest to standâor driveâtoday between Astorgus and his seven straight triumphs. He'd bruised his shoulder in a fall in mid-session last time, and hadn't been running when Astorgus won that magnificent four-in-a-row at the end of the day.

It offended Fotius that a dark-skinned, scarcely bearded upstart from the deserts of Ammuzâor wherever he was fromâcould be such a threat to his beloved Astorgus. He

ought

to have bought the curse-tablet, he thought ruefully. An apprentice in the linen guild had been knifed in a dockside caupona two days before and was newly buried: a perfect chance for those with tablets to seek intercession at the grave of the violently dead. Everyone knew that made the inscribed curses more powerful. Fotius decided he'd have only himself to blame if Astorgus failed today. He had no idea how he'd pay Pappio if he lost. He chose not to think about that, or about his wife's reaction.

âUp the Blues!' he shouted suddenly. A score of men near him roused themselves to echo the cry.

âUp the Blues in their butts!' came the predictable reply from across the way.

âIf there were any Greens with balls!' a man beside Fotius yelled back. Fotius laughed in the shadows. The white moon was hidden now, over behind the Imperial Palaces. Dawn was coming, Jad in his chariot riding up in the east from his dark journey under the world.

And then the mortal chariots would run, in the god's glorious name, all through a summer's day in the holy city of Sarantium. And the Blues, Jad willing, would triumph over the stinking Greens, who were no better than barbarians or pagan Bassanids or even Kindath, as everyone knew.

â

Look

,' someone said sharply, and pointed.

Fotius turned. He actually heard the marching footsteps before he saw the soldiers appear, shadows out of the shadows, through the Bronze Gate at the western end of the square.

The Excubitors, hundreds of them, armed and armoured beneath their gold-and-red tunics, came into the Hippodrome Forum from the Imperial Precinct. That was unusual enough at this hour to actually be terrifying. There had been two small riots in the past year, when the more rabid partisans of the two colours had come to blows. Knives had appeared, and staves, and the Excubitors had been summoned to help the Urban Prefect's men quell them. Quelling by the Imperial Guard of Sarantium was not a mild process. A score of dead had strewn the stones afterwards both times.