The Sagas of the Icelanders (3 page)

Read The Sagas of the Icelanders Online

Authors: Jane Smilely

In Iceland, the age of the Vikings is also called the Saga Age. About forty interesting and original works of medieval Icelandic literature are fictionalized accounts of events that took place in Iceland during the time of the Vikings: from shortly before the settlement of Iceland about 870 to somewhat after the conversion to Christianity in the year 1000. They were written mainly in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, but they concern characters and events in Iceland, and to some extent the larger Norse world, from three hundred years earlier. All of the sagas in this collection are historical fictions of this type, a form known in Icelandic as

Íslendinga sögur

(sagas of Icelanders) and often in English as ‘family sagas’. These works are the crowning achievement of medieval narrative art in Scandinavia, and when people speak of ‘the Icelandic sagas’ they usually mean the

Íslendinga sögur

.

In spirit the

Íslendinga sögur

are much like epics. While women are more prominent and interesting characters in the sagas than in Homeric epic or

Beowulf

or the

Song of Roland

, the world of the sagas is still a man’s world. Such heroic virtues as honour, fortitude and manly courage count for a great deal, and the definition of heroes in a variety of situations is one of the main points. The sagas differ from epics in two important ways: formally, by being in straightforward, clear prose rather than verse, and culturally, by not being about kings and princes and semi-divine heroes but about wealthy and powerful farmers.

Saga heroes occupy a social space on the edges of society. The heroes of three of the sagas,

The Saga of Grettir the Strong, Gisli Sursson’s Saga

and

The Saga of Hord and the People of Holm

, are in fact outlaws. Gunnar Hamundarson of Hlidarendi in

Njal’s Saga

is also technically a criminal when he is killed. Most of the saga heroes are just barely on one side or the other of the law, but it also seems to be true that the law itself is being tested along with the finest men. Epic and saga are enough alike to make a comparison interesting and instructive, especially in the degree to which both genres synthesize history, myth, ethical values and descriptions of actual life. Sagas differ from romance, the other great medieval narrative mode, by focusing attention on actual social types of people in a historically and geographically precise context, with little apparent interest in fantasy and the spiritual and psychological experience of what is sometimes called ‘courtly love’. There are

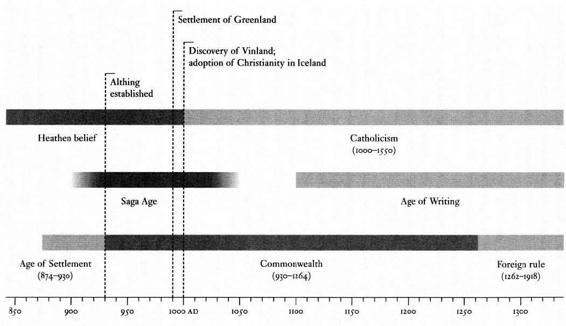

Ages of Icelandic History

lovers in the sagas, but far less frequently do they end happily ever after than do their counterparts in romance. Generically, the sagas stand not so much between epic and romance as between epic and that other great European narrative form, the novel.

The word

saga

is related to the English word

say

. Its various meanings in Icelandic can be roughly understood as denoting something said, a narrative in prose. English has no precise equivalent, so

saga

often appears in the titles of Icelandic books untranslated, although ‘story’, ‘tale’ or ‘history’ would come close, with some combination of the three even closer. Literary scholars now distinguish several kinds of sagas, depending on subject matter or historical setting. In addition to the

Íslendinga sögur

, with which we are concerned here, there are chivalric romances (

riddarasögur

); legendary sagas of pre-Icelandic Germanic heroes (

fornaldarsb’gur

); lives of the kings of Norway (in the great collection called

Heimskringla

and other individual

konungasogur

); saints’ lives (

heilagra manna sögur

); and histories of ‘contemporary’ events (

samtidarsogur

) that took place in Iceland after the Saga Age, many of which are preserved in the huge collection known as

Sturlunga saga

and others in the lives of Icelandic bishops (

biskupasdgur

).

Closely related to the

Íslendinga sögur

is a genre of short tales called

Íslendinga pnettir

(tales of Icelanders), six of which have been selected for inclusion in this collection.

pattir

(plural

þœtir

) means, among other things, ‘part’ or ‘chapter’, and the

Íslendingapattir

do, whether they occur separately or as part of a larger work, give the appearance of being anecdotes that can perform a variety of functions within a larger work, such as illustrating a king’s character or providing an authenticating historical or learned detail. They occur mostly in large manuscript collections of kings’ sagas and often concern some kind of comic encounter between a humble Icelander and a king of Norway, frequently Harald Sigurdarson the Stern, in which an initial conflict is resolved.

The characters in many of the

þœttir

are familiar to us from the roles they play in the sagas, and take on a special interest for this reason, as though they exist in a network of story that is larger than that encompassed by any single text or group of texts. The texts we have are, from this perspective, but a selection from the events of this larger saga world, in which ultimately every

Íslendinga saga

is connected to all the others.

Whether a short narrative is titled a ‘saga’ or a ‘tale’ sometimes seems quite arbitrary, and while the categories of saga narrative are useful and the various kinds of sagas can be distinguished fairly easily, they do overlap. Individual works have their own character and are often somewhat ‘mixed’ in style. An example of a short and entertaining saga with many of the features of a ‘tale’ is

The Saga of Ref the Sly

. The hero’s name, Ref, means ‘fox’ in Icelandic, and he can be thought of as ‘the sly fox’, which King Harald the Stern had in mind when he gave him ‘the sly’ as a nickname. Like many of the tales of Icelanders,

The Saga of Ref the Sly

does not involve trolls or berserks or the supernatural for its entertainment, but Ref’s extraordinary skill and ingenuity in highly naturalistic settings in Iceland, Greenland, Norway and Denmark.

Ref the Sly

is unique among all the sagas in allowing itself the anachronism of a reference to writing (

Ch. 6

). Ref is asked by his uncle as he is leaving Iceland to have his adventures written down in case he does not come back. The rationalism and ingenuity of the story, the identification of the hero as a fox and the reference to writing as a way of preserving the hero’s exploits, all point towards the likelihood that the widespread literary tradition of

Reynard the Fox

is here given Icelandic attire.

The

Íslendinga sögur

are, however, in some cases quite hospitable to elements found abundantly in the legendary

fornaldarsögur

, such as trolls, ghosts, berserks and magical enchantments. On the other hand, the seriousness of their intellectual purpose gives the

Íslendinga sögur

much in common with the sagas of contemporary Icelanders and the kings’ sagas. The freshest approaches to saga narrative in Icelandic scholarship today concern the fringes and overlappings of saga genres. The sagas are being seen as stylistically more self-conscious than we have realized, raising new questions of controlled parodies, in which stylistic effects may have been designed to produce humour and subtle, at times touching or nostalgic, reminders of a time and a sensibility from which the reader is for better or for worse now cut off.

Prose as good as that which evolved into the classic saga style was rare in medieval European literature. It tended to appear later, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Exceptions do exist, such as the

Decameron

of Boccaccio and (much closer in spirit to the sagas) the French Vulgate cycle of Arthurian romances. Still, the development of a prose fiction in medieval Iceland that was fluent, nuanced and seriously occupied with the legal, moral and political life of a whole society of ordinary people was an achievement unparalleled elsewhere in Europe.

The most famous manuscript to survive in Iceland from the Middle Ages is not a saga. It is a collection of poems about Odin and the other gods and about the major characters in the heroic story of the Volsungs. Like several other old Icelandic books, the physical object is named

Codex Regius

(The King’s Book). The manuscript itself was written about 1270, but is based on somewhat older written texts. The anthology of poems it contains has traditionally been known in English as the

Poetic Edda

. We do not know who compiled the

Codex Regius

of the

Poetic Edda

nor very much about the history of the texts that it contains. The poems are arranged according to a plan and interjected prose passages provide narrative contexts for many of them. The metre and diction of these poems link them to a much earlier Germanic poetics, as illustrated in Anglo-Saxon, Old Saxon and Old High German poetry. Despite the antiquity of its roots everything points to the compilation of

Codex Regius

as being, like many of the sagas, an achievement of the thirteenth century.

Another thirteenth-century work, as precious as the

Poetic Edda

, also concerns myth and poetry. It is believed to have been written by Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) and is called

Snorra-Edda

in Icelandic. In English it is usually known as the

Prose Edda

. Intended no doubt as a kind of textbook, it begins with a retelling of the myths and legends found in the

Poetic Edda

, often amplifying and clarifying them. But then it develops in the second section, called

The Poetics (Skdldskaparmdl

), into a truly remarkable treatise on poetry, with examples of complex poetic metaphors that were based on the myths, as well as examples of poetic forms. Nothing like

Snorra-Edda

exists anywhere else in medieval European literature. These two separate works, one entitled

Edda

by its author, the other acquiring the name in modern times by association with Snorri’s book, illustrate the extent to which Icelanders of the thirteenth century felt an impulse to collect and preserve what they could of the culture of pagan antiquity. As were the

Íslendinga sögur

, the two books called

Edda

were antiquarian efforts to preserve a distant past through the perspective of a liberal and inquisitive impulse in thirteenth-century Christian scholarship. They illustrate likewise the balanced attention that was directed by thirteenth-century literary culture to prose and poetry. It was a golden age, in which many kinds of stories and literary forms were familiar to readers of the

Íslendinga sögur

.

The genres of thirteenth-century Icelandic literature were not restricted to the sagas and eddas. The kinds of knowledge that formed the basis for a conventional medieval education in religion and the liberal arts were also set down in books.

The Icelandic Homily Book

(composed around 1200) mentions a number of learned medieval authors from whom ideas have been received: Pope Gregory the Great, St Augustine, the Venerable Bede, Alcuin, Fulgentius. There were Icelandic translations of

Elucidarius

by Honorius Augustodunensis and a

Physiologus

, as well as the works of other important authors. These translations appear in various collections, such as the fourteenth-century

Hauksbók

. In addition to these more commonplace elements of medieval intellectual life, some particularly Icelandic matters, close in spirit to the sagas, were also written early, and the Icelandic laws were among the first, in the early twelfth century. Since the adoption of a national constitution in 930, the laws of the Icelandic Commonwealth (

pjodveldi

) had been recited by the Lawspeaker (

logsogumaSur

), one-third each year for three years, at the national assembly, the Althing (

Alpingi

), which met on the plains of the Althing, Thingvellir, every June. The circumstances of their writing are described in a small book called

Íslendingabók

(The Book of Icelanders), written about 1130 by the priest Ari Thorgilsson (1068–1148), known as ‘the Learned’: in 1117 the innovation was decided upon at the Althing of having sections of the law written in a book during the following winter. Accordingly, at the home of Haflidi Masson, the laws were dictated by the Lawspeaker, Bergthor Hrafnsson, and written down under his supervision and that of other wise men. They were read the following summer to the unanimous approval of the Althing.