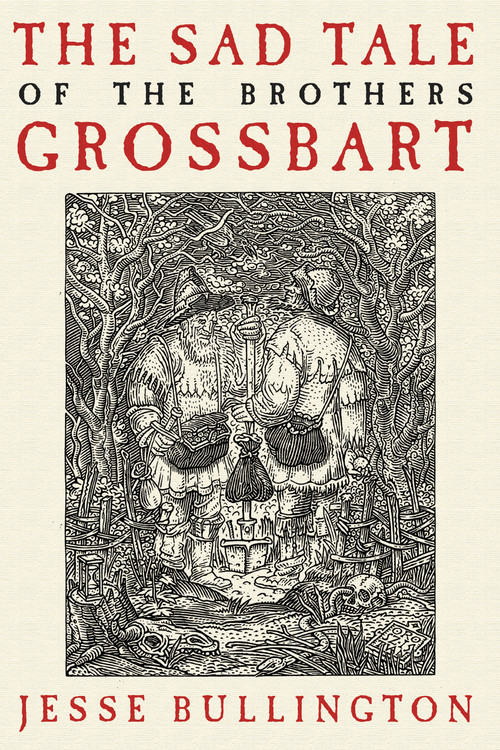

The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart

The year is 1364. Hungry creatures stalk the

dark woods of medieval Europe, and both sea

and sky teem with unspeakable horrors.

This is the world of the Brothers Grossbart…

“What is this

fuck

?” Martyn asked.

“What?” Hegel said.

“Who?” Manfried said.

“Fuck,” Martyn repeated, “fucking, fuck, fucker—the word you like so much. A slur?”

“Oh, the

word

fuck!” Manfried laughed. “Yeah, a slur, right enough. Village not too far from our birth-home’s called Fuckin.”

“Why did they name it after a slur?” asked Martyn.

“Oft have I mused the same question,” said Hegel.

“You have?” Manfried grinned at his brother’s folly. “Hardly surprisin. Nah, Martyn, it’s like this. Fuckin’s a town filled

with men what are assholes, but assholes so mecky it don’t serve to just call’em assholes or mecky assholes or even Maryless

mecky assholes, gotta get somethin stronger by way a differentiatin, to say nuthin a brevity. Hence, we call someone so mecky

they might’s well been from Fuckin a fucker or a fuckwit or anythin else related to bein from Fuckin. Yeah?”

There was a long silence on the bench before Hegel cleared his throat. “Or the act a fornication. Bein a mecky deed, the term

may be applied there as well.”

Copyright © 2009 by Jesse Bullington

Excerpt from

The Company

copyright © 2008 by K. J. Parker

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Orbit

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: November 2009

Orbit is an imprint of Hachette Book Group. The Orbit name and logo are trademarks of Little, Brown Book Group Limited.

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and

not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07192-5

Contents

VI: The Teeth of a Donated Horse

VII: A Cautionary Yarn, Spun for Fathers and Daughters Alike

X: Fresh Paths and Good Intentions

XII: A Telling on the Mountain

XIII: The Start of a Tale Already Concluded

XVII: The Difficult Homecoming

XIX: Like the Beginning, the End of Winter Is Difficult to Gauge in the South

XXI: The Conflagration of Desires

XXIV: The Execution of the Grossbarts

XXIX: Like the End, the Beginning of Winter Is Difficult to Gauge in the South

Dedicated to

Raechel

Molly

John

David

Travis

Jonathan

The story of the Brothers Grossbart does not begin with the discovery of the illuminated pages comprising

Die Tragödie der Brüder Große Bärte

tucked inside a half-copied Bible in a German monastery five hundred years ago, nor does it end with the incineration of

those irreplaceable artifacts during the firebombing of Dresden last century. Even the myriad oral accounts that were eventually

transcribed into the aforementioned codex by an unremembered monk hardly constitute a true starting point, and, as the recent

resurgence in scholarship testifies, the chronicle of the Grossbarts has not yet concluded. The pan-cultural perseverance

of these medieval tales makes the lack of a definitive modern translation even more puzzling, with the only texts available

to the contemporary reader being the handful of remaining nineteenth-century reprints of the original documents and the mercifully

out-of-print verse translations of Trevor Caleb Walker. That Walker was a better scholar than a poet is nowhere more evident

than in that vanity edition, and thus came the impetus to retell

Die Tragödie

in a manner that would transmit the story as it would have been appreciated by its original audience.

The distinction here between stories and story represents what is, presumably, a first in the field—rather than treating

Die Tragödie

as a collection of independent fragments, comparable to the contemporaneous

Romance of Reynard

, I have focused on the quest continuously reiterated by the Grossbarts themselves in order to cobble together a cohesive

and linear narrative. A benefit of transforming the work into a single account is the inclusion of previously unlinked stories,

divergences that illuminate aspects of the greater narrative even if they at first seem quite disparate save for their era

and locale. Another consequence of this approach is that small leaps occasionally occur in the journey as overly repetitious

adventures are elided.

Scholars curious as to whether this humble author sides with the apologists Dunn and Ardanuy or the revisionists Rahimi and

Tanzer will be disappointed—this tale is intended for those members of the public having no previous acquaintance with the

Grossbarts, and is thus unadorned with academic grandstanding. For this reason, and to avoid unduly distracting the average

reader, the following pages lack annotation, with the most popular interpretation of any given incident defaulted to when

variations arise. As has already been stated, the adventures of the Grossbarts are often remarkably similar save for locale—reflecting

regional differences on the part of the original storytellers—and so marking up these deviations would defeat the entire purpose

of the project, which is to convey the tale as it would have come across in its original form. After all, the average German

serf would be no more aware that his Dutch neighbors blamed his region for spawning the Grossbarts than the merchant of Dordrecht

would be that down in Bad Endorf the Germans insisted his town was where the twins were born.

This is indicative of the gulf separating contemporary readers from the original audience, an audience alien almost to the

point of incomprehensibility. Those first storytellers and listeners might, for example, have taken the fantastic and violent

elements much more seriously with only hearth or campfire to stave off the perilous night. The fourteenth century, wherein

the tales were both told and set, was, as Barbara Tuchman opens her history of that era, a “violent, tormented, bewildered,

suffering and disintegrating age, a time, as many thought, of Satan triumphant.”

Yet it was no arbitrary decision that led Tuchman to title that work

A Distant Mirror

. Tragedies and atrocities may seem inherently worse when appraised from long after they occurred, but despite all we have

accomplished wars rage, righteous uprisings are viciously suppressed, religious persecution thrives, famine and plague decimate

the innocent. This is not to excuse or apologize for any cruelties peppering the following pages, but simply to provide a

lens, should the reader require one, through which to view them.

We will never know if the Grossbarts were heroes or villains, for as Margaret Atwood observes in her novel

The Handmaid’s Tale

, “We may call Eurydice forth from the world of the dead, but we cannot make her answer; and when we turn to look at her we

glimpse her only for a moment, before she slips from our grasp and flees.” That the Grossbarts themselves would take umbrage

at both being associated with the witchery of Orpheus’ quest to the underworld and this particular account of their deeds

seems probable, but whether their medieval audience would approve remains forever unknowable. This tale is exhumed for our

enlightenment, and while I have done some tailoring for our modern sensibilities their spirit remains just that, and as such,

unquenchable. “As all historians know,” Atwood concludes that selfsame quote, “the past is a great darkness, and filled with

echoes. Voices may reach us from it; but what they say to us is imbued with the obscurity of the matrix out of which they

come; and, try as we may, we cannot always decipher them precisely in the clearer light of our own day.” With that wisdom

in mind, let us cock our ears and squint our eyes toward the Brothers Grossbart and a beginning in Bad Endorf.

The First Blasphemy

To claim that the Brothers Grossbart were cruel and selfish brigands is to slander even the nastiest highwayman, and to say

they were murderous swine is an insult to even the filthiest boar. They were Grossbarts through and true, and in many lands

such a title still carries serious weight. While not as repugnant as their father nor as cunning as his, horrible though both

men were, the Brothers proved worse. Blood can go bad in a single generation or it can be distilled down through the ages

into something truly wicked, which was the case with those abominable twins, Hegel and Manfried.

Both were average of height but scrawny of trunk. Manfried possessed disproportionately large ears, while Hegel’s nose dwarfed

many a turnip in size and knobbiness. Hegel’s copper hair and bushy eyebrows contrasted the matted silver of his brother’s

crown, and both were pockmarked and gaunt of cheek. They had each seen only twenty-five years but possessed beards of such

noteworthy length that from even a short distance they were often mistaken for old men. Whose was longest proved a constant

bone of contention between the two.

Before being caught and hanged in some dismal village far to the north, their father passed on the family trade; assuming

the burglarizing of graveyards can be considered a gainful occupation. Long before their granddad’s time the name Grossbart

was synonymous with skulduggery of the shadiest sort, but only as cemeteries grew into something more than potter’s fields

did the family truly find its calling. Their father abandoned them to their mother when they were barely old enough to raise

a prybar and went in search of his fortune, just as his father had disappeared when he was but a fledgling sneak-thief.