The Roughest Riders (10 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

Shafter was also an old veteran, a year older than Wheeler at sixty-three. He accepted a commission in a Michigan volunteer unit during the Civil War and received the nation's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Fair Oaks, where he was wounded. He was taken prisoner at the Battle of Thompson's Station and spent three months in a Confederate

jail. After his release, he was appointed colonel of the all-black Seventeenth Regiment and led it at the Battle of Nashville. By the time the war ended, he had risen to the rank of brigadier general. In the early 1890s, Shafter fought on the American frontier in the Indian Wars and earned the soubriquet “Pecos Bill” during his campaigns against the Cheyenne, Comanche, and other tribes.

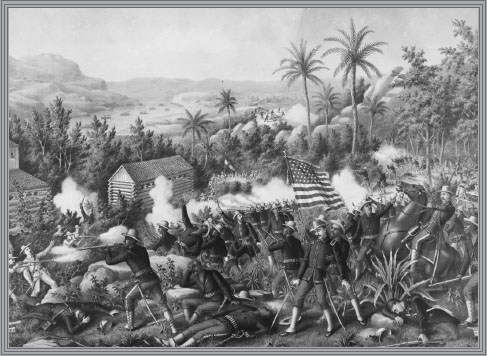

General Wheeler (left) was inclined to defy orders from his superior, General Shafter (right), whose tactics he regarded as too timid. They had fought on opposite sides during the Civil War, and Wheeler sometimes got his wars mixed up when he referred to the Spaniards as “damn Yankees.”

Commons.Wikimedia.Org

Not only were Shafter and Wheeler physical opposites, but they had fought on opposing sides during the Civil War. The gargantuan, ailing Shafter was regarded as an unlikely candidate for his commanding role in Cuba. He was past his prime, as was Wheeler, and the two men resented each other.

The soldiers who camped that first night in Daiquiri immediately came under attackânot from enemy soldiers, as they'd feared, but from giant land crabs the size of small dogs that crawled into the two-man tents and skittered over the men while they attempted to sleep. The Americans had never seen anything like them before, not even the Westerners who were used to encountering snakes, scorpions, tarantulas, lizards, and all sorts of pinching and biting creatures in the desert. No one had ever seen crabs of this magnitude, and they fought them off throughout the night, unable to get much-needed rest during the ordeal. Fortunately, the crabs were scavengers that ate only carrion and weren't interested in live meat.

The crabs were gone by morning, and above the men and their campsites loomed the mountains with virtually impassable roads. Beyond them, eighteen miles of thick jungle teemed with venomous snakes and other reptiles, slithering and crawling over the hills between the troops and their primary objective: the town of Santiago de Cuba.

The Twenty-Fifth black infantry and some white units were under the command of General Henry Lawton. General Shafter devised a plan for Lawton's divisions to take the lead, trekking from the beach toward Siboney over rugged and swampy coastal

terrain. Bringing up the rear would be a cavalry division composed of regulars and volunteers, including the black Ninth and Tenth, a few white units, and the Rough Riders, all dismounted except for Roosevelt, Wood, and some of the other officers. They were under the command of General Wheeler, who hated the idea of being in the rear, since he wanted to lead the charge against those Yankees up in the hills.

“That night about 7 o'clock the Captain asked the First Sergeant to send me to him,” wrote C. D. Kirby with the black Ninth. “I reported to the Captain, who asked me if I was afraid of the Spaniards, and I replied that I was not afraid of anything, whereupon the Captain ordered me to take my gun and belt and report to him. I soon returned and he said, âI want you to go to the dock and watch the grub, and if anyone comes around there kill him.'”

It was pitch black where Kirby was stationed, but at about 12:30 in the morning he made out two figures approaching in the dark through the brush. Kirby remained quiet until they drew closer. He admitted that he was shaking with fear, but he held his ground and commanded them to halt. They ignored his warning and kept on coming. Kirby called out twice more in a loud voice, but still the two figures kept approaching. Finally, Kirby stepped behind a rock, took aim, and shot one of the men, killing him on the spot. The dead soldier's companion shot back and missed, the bullet glancing off a rock and winging Kirby on the shoulder. Kirby shot him too, knocking him to the ground but not killing him. Kirby advanced and asked the man how he was feeling. “Pretty bad,” the Spaniard said. Kirby slammed him across the head with the butt of his pistol, knocking him unconscious and temporarily putting him out of his misery. For this incident, as well as his action in combat later, the captain gave the black trooper the name “Brave Fighting Kirby.”

Around dawn, the order came for the first column of men, including the Buffalo Soldiers of the Twenty-Fifth, to leave

immediately and push along on the path to Siboney. The black Ninth and Tenth stayed behind with Wheeler's forces, also serving under his second-in-command, General Samuel B. M. Young. The Twenty-Fifth and some white units marched single file on the unpaved trail, with orders to hook up with the black Twenty-Fourth under General Jacob Kent after they landed. The Twenty-Fifth and their white compatriots left almost as soon as they hit the beach and made first camp around 8:30 that evening.

“We marched about four and a half miles through the mountains; then we made camp,” a black soldier with the Twenty-Fifth wrote later. Another with the same outfit wrote, “A short distance ahead (from the shore) we bivouacked for the night. We were soon lying in dreamland, so far from friends and home, indeed, on a distant, distant shore.”

A white staff officer described the movement similarly in his own account of the action: “General Lawton, with his Division, in obedience to this order, pushed forward from Daiquiri about five miles, when night overtook him and he bivouacked on the road.” The campsite was a brush-covered flat with heavy jungle growth on one side and a shallow, stagnant pool on the other. The men dined on canned meat and beans heated on open fires; hardtack; and coconuts and chili peppers they found in the area, all washed down with coffee made from river water.

The rainy season had arrived, making the going more treacherous as the men slogged over muddy trails beneath dripping canopies of trees. The land crabs returned, their appetites for carrion intensified with the advent of the steady tropical downpours, turning them into even more formidable adversaries than the men had first thought. The Spanish proved to be less of a problem, offering only token resistance at Siboney, which the first column of Americans occupied on the morning of June 23. Shafter had instructed Lawton to remain there while the rest of the supplies were being

unloaded onto the beach at Siboney, now that his troops were in control there.

Wheeler and Roosevelt fumed at being left behind at the Daiquiri campsite to guard against any possible Spanish rearguard assault. Each of them had trouble containing his urge to be in the middle of the fighting, one to enhance his military career and the other his political one. Fighting Joe decided to take action on his own, defying Shafter's orders. He left Daiquiri with a squad of scouts early on June 23, and Young followed closely behind with some white regulars and some black soldiers from the Ninth and Tenth. Wheeler infuriated Roosevelt all the more with his order for Roosevelt to stay behind with his band of Rough Riders.

Wheeler was surprised to see that the Spaniards had not defended the route to Siboney at several locations where they could have had a distinct advantage over the Americans grinding their way along the trail. Lawton was almost speechless when he saw Wheeler and his scouts tromping unannounced into his campsite. Wheeler informed Lawton that he had learned from Cuban rebels on the way that Spanish forces lay well entrenched at a fork in the trail three or four miles inland. Wheeler wanted to march uphill and assault the position directly, but Lawton viewed the situation differently. Lawton preferred to take a more circuitous route along the seacoast and attack the Spanish flank, forcing them toward Santiago at the risk of being cut off from their main line of defense. The two generals stood there at loggerheads, one obeying his commander's orders, the other in open defiance of them.

G

eneral Shafter sat hobbled by gout on his ship, observing the activity on the coast the best he could through field glasses. Richard Harding Davis, a reporter for the

New York Herald

, vividly captured the scene during the landing:

It was one of the most weird and remarkable scenes of the war, probably of any war. An army was being landed on an enemy's coast at the dead of night, but with somewhat more of cheers and shrieks and laughter than rise from the bathers in the surf at Coney Island on a hot Sunday. It was a pandemonium of noises. The men still to be landed from the “prison hulks,” as they called the transports, were singing in chorus, the men already on shore were dancing naked around the camp fires on the beach, or shouting with delight as they plunged into the first bath that had been offered in seven days, and those in the launches as they were pitched head-first at the soil of Cuba, signalized their arrival by howls of triumph. On either side rose black, overhanging ridges, in the lowland between were white tents and burning fires, and from the ocean came the blazing, dazzling e

y

es of the search-lights shaming the quie

t

moonlight.

For his part, Shafter sat immobilized by his throbbing foot and the oppressive heat and humidity bearing down on him. He tried to make what sense he could of the men milling about on the shore, but he couldn't be sure which troops were Lawton's and which were Wheeler's amid the chaos. His mood was soured all the more by the lack of communication from his men on land.

The place that lay a few miles uphill at the crossroads was called Las Guasimas, named for the fruit-bearing trees that adorned the hill. Before the Spanish had chased them out, the locals used to pluck the fruit and feed it to their pigs. Richard Harding Davis, one of the handful of writers who reported from the scene, depicted the site as “not even a village, nor even a collection of houses.” Two trails came together there, forming the apex of a V. The site was located about three miles inland from Siboney. From the point where they met, the trails merged and continued along a single trail toward Santiago. General Wheeler took it upon himself to reconnoiter the area in the company of some Cuban rebels. He declared openly that he intended to attack Las Guasimas in the morning, whether Shafter authorized it or not.

While Lawton and Wheeler debated military strategy, Roosevelt sat stewing with his Rough Riders on the beach in Daiquiri. They glumly ate a lunch of bacon and beans while Roosevelt reined in his urge to get moving along the route Wheeler had taken earlier. Finally, at 1:30 in the afternoon of June 23, Colonel Wood told Roosevelt that he received an order from Wheeler for the Rough Riders to strike out along the coast toward Siboney. In addition to a supply of rations, they planned to carry with them an assortment of picks, shovels, and other equipment that would come in handy for digging trenches. Their mule train was reduced to 16 animals

from the 189 they had started with in San Antonio; some had been left behind in Florida, and others never made the swim to shore. But before they got under way, Wood decided to leave the slimmed-down mule train with all the equipment in Daiquiri to speed up their journey. They compensated by taking with them some extra first-aid kits instead.