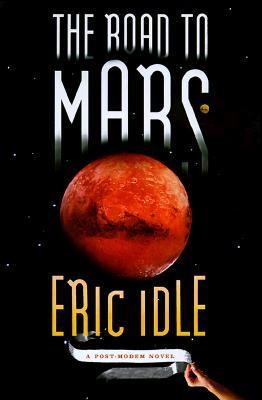

The Road to Mars: A Post-Modem Novel (1999)

Read The Road to Mars: A Post-Modem Novel (1999) Online

Authors: Eric Idle

|

Eric Idle

The Road to Mars

A Post-Modem Novel

1999

With

Monty Python’s Flying Circus

, Eric Idle proved he was one of the funniest people in the world. And with

The Road to Mars

he reaffirms this with a raucously sidesplitting vengence.

Muscroft and Ashby are a comedy team on

The Road to Mars

, an interplanetary vaudeville circuit of the future. Accompanied by Carlton, a robot incapable of understanding irony but driven to learn the essence of humor, Alex and Lewis bumble their way into an intergalactic terrorist plot. Supported by a delicious cast, including a micropaleontologist narrator (he studies the evolutionary impact of the last ten minutes) and the ultra-diva Brenda Woolley,

The Road to Mars

is a fabulous trip through Eric Idle’s inimitable world, a “universe expanding at the speed of laughter.”

Fame

FameLet us now praise famous men,

and our fathers that begat us.

—

Ecclesiasticus

Fame is a fickle food

Upon a shifting plate.

—

Emily Dickinson

Fame is a terminal disease. It screws you up worse than your mom and dad. Somewhere in the late twentieth century the pursuit of fame became a way of life. Suddenly everyone wanted to be famous. Newscasters, journalists, weather men, astrologers, cooks, interns, even lawyers for God’s sake, everyone went nuts trying to grab their fifteen minutes of fame promised by the pop philosophy of Andy Warhol. It replaced life after death as mankind’s greatest illusion. Fame! You’ll live forever. Fame! Your chance to revenge your parents. Fame! Take that, you nasty kids who were so cruel to me at school. Fame! A chance to screw yourself across the flickering face of history.

Fame, fame, fame, fame, fame.

This syphilis of the soul was caused of course by the arrival of television and the instant attention of the new mass media. If the medium was the message, then the message was crap, for the TV screens were filled from morning to night with a constant twenty-four-hour shit storm. No one was spared. Not presidents, not princes, not popes, not people’s representatives. Knickers off, panties down, coming live at you in ten, nine, eight…Kiss and tell, kiss and sell, bug your neighbors, tape your friends, grab an agent and sell, sell, sell. Intimacy? Privacy? Forget it. Notoriety? Shame? No such thing. Fame. That’s the name of the game. Private life was washed away under the tidal wave of freedom of speech. It didn’t matter whether you were famous for murdering a president or inventing a pudding, now fame could travel at the speed of light, everyone was just a sound bite from stardom.

No one remembers the name of the anarchist who started World War One by murdering the archduke in Sarajevo in 1914. Everyone remembers Lee Harvey Oswald. Fame! A rifle shot away. Providing you have television. Fame, the intellectual equivalent of waving at the camera. “Look at me, Ma! I’m here. I’m real. I’m on TV.” Sad, sick, and deplorable, isn’t it? I mean in the 1990

s

even agents became famous, for Christ’s sake. And what do we call the famous? Stars! I mean hello. Have we no sense of irony? Look up-look up at the real stars. Billions of them? Billions and billions of the buggers. Don’t we get it? There is no fame. There is no immortality. There is no life after death. There are just millions of tiny grains of sand scraping away at each other. We’re on the planet Ozymandias, people! Look on my works ye mighty and despair! The grains of time, grinding away at our insignificance…well you get the picture. You’re intelligent. You’ve read this far at least.

But who the fuck are you to lecture us on our insignificance? I hear you ask. Not unreasonably. OK, my name is Reynolds. Given name William. Better known as Bill. Actually, Professor Bill, which is better than William, and much better than the quite awful Billy. And that’s what I do: I lecture on insignificance. I’m a micropaleontologist. You may be unaware of the study labeled micropaleontology (occasionally microanthropology), which was the first really brand-new science of the Double Ages (the second millennium). It is my job to study

the evolutionary implications of the last ten minutes

. Originally that phrase was a cheap gag intended to belittle this brave new science, this paradoxically titled branch of anthropology—for how can there be a micropaleontology? What are we talking ontologically here? Dust mites? Bakelite radio sets? Dung heaps of old newspapers which will over time become rock? Well actually, yes. If you can measure time in parsecs and millisecs, and matter down to the tiniest gluon, then the evolutionary aspects of the last ten minutes is a perfectly acceptable concept. So argued Edwin Crawford at Cambridge University shortly after the close of the twentieth century. He was pondering the enormous changes that had taken place during that violent era and he asked himself, What are the evolutionary implications of television? He found that similar questions could be asked of the automobile, birth control, the computer, air travel, even rock and roll. It seemed to Crawford that the process of evolution was demonstrably speeding up, that we had no time to wait for anthropologists and paleontologists to sift through the fossil record and explain what was happening to us in our time.

It would be far too late to be useful

. (His italics.) So, a new science was born.

My particular subject has been comedy in the late twentieth century, and I have spent the last fifteen years researching it. My doctoral thesis was called “The Passive Bark: Aspects of Laughter.” Yes, I know, I know, it is the hallmark of the desperately unfunny to study comedy, as if somehow it could be learned, as if it might be contagious like a virus picked up and passed on, but that indeed was exactly what I was studying when I was fortunate enough to stumble across the work of Carlton. You won’t have heard of him, but he was the first to postulate a comedy gene, in a remarkable work titled

De Rerum Comoedia

(Concerning Comedy), a doctoral dissertation for USSAT (the University of Southern Saturn) submitted in the late 2300

s

. The most interesting thing about Carlton was not that he was an android, an artificial intelligence, but that he worked for two comedians, Muscroft and Ashby. You won’t have heard of them either; they were just two minor comics on the Road to Mars, an ironical term used to describe the great wastes between the outer planets and mining stations where the early entertainers pursued their weary trade; a vaudeville circuit which exploited mankind’s desperate need for live entertainment. They were hardly worth a footnote in the halls of humor but for the work of this quite brilliant humanoid who spent years observing them in action and asked himself two key questions: (1) What are the evolutionary uses of humor? And (2) Can it be learned by artificial intelligence?

The chess machines had long since demolished mankind’s supposed superiority in chess. Could a machine now be programmed to

be funny?

I don’t mean could it be force-fed gags to spout on verbal cues—that’s easy enough—but could it actually be programmed to understand what it was doing, to

think

funny, to create fresh comedy? In other words, is it possible for an artificial intelligence to learn humor, or is comedy something endemic in the species

Homo sapiens?

Is it unique to mankind or would you expect to find humor among any other advanced civilizations, supposing such things exist?

Carlton attacked these questions with all the vigor and freshness of a computer. This extraordinary humanoid looked at humor and came up with several interesting observations. I think you’ll be surprised. To put his research in perspective I need to take you back about eighty years.

Of the future only one thing is certain. There will be comedy.

—

Carlton, De Rerum Comoedia

Consider the following. Two comedians, Muscroft and Ashby, and a robot, a droid called Carlton. A 4.5 Bowie. A handsome, good-looking thing, built on the image of a young rock god from the 1980

s

. Not the androgynous early Ziggie Stardust machine (the 3.2

s

with which they had such trouble), but the full-blown golden-haired young white god look. “Like a butch Rupert Brooke; a tragic dandy, a cross between a wank and a wet dream,” as the brochure described it.

Two comedians, one a depressive who was occasionally manic, the other a maniac who was occasionally depressed. Lewis Ashby, tall, dark, and saturnine; Alex Muscroft, short, wide, and cheerful. Lewis, the ectomorph; Alex, the endomorph. The classic comedy profile, the tall thin one and the short fat one.

“There are two types of comedian,” states Carlton in the preface to his dissertation, “both deriving from the circus, which I shall call the White Face and the Red Nose. Almost all comedians fall into one or the other of these two simple archetypes. In the circus, the White Face is the controlling clown with the deathly pale masklike face who never takes a pie; the Red Nose is the subversive clown with the yellow and red makeup who takes all the pies and the pratfalls and the buckets of water and the banana skins. The White Face represents the mind, reminding humanity of the constant mocking presence of death; the Red Nose represents the body, reminding mankind of its constant embarrassing vulgarities. (See Chapter XX of

De Rerum Comoedia

, ‘Pooh-Pooh: Pooping, Farts, and Sex.’) The emblem of the White Face is the skull, that of the Red Nose is the phallus. One stems from the plague, the other from the carnival. The bleakness of the funeral, the wildness of the orgy. The graveyard and the fiesta. The brain and the penis. Hamlet and Falstaff. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Laurel and Hardy. Muscroft and Ashby.”

You try it with any comedians you can think of, and I tell you it works. Carlton, this smart little tintellectual, is on to something real here. Just look for the distinguishing characteristics: the White Face is the controlling neurotic and the Red Nose is the rude, rough Pan. The White Face compels your respect; the Red Nose begs for it. The Red Nose smiles and nods and winks, and wants your love; the White Face rejects it. He never smiles; he is always deadly serious. Never more so than when doing comedy.

“Men,” says Carlton, “have two major organs, the brain and the penis, and only enough blood to run one at a time.”

He nicked that line from Alex, but it’s clever stuff, eh? And he pretty much nailed Alex, the Red Nose maniac, and Lewis, the bright-eyed White Face neurotic. Physically they

were

that clearly defined, the classic prototypes that Carlton was delineating. Lewis was “the tall thin one” and Alex “the short fat one.” People often said Alex was the funny one, but Lewis was equally funny, if more cutting. He didn’t take any prisoners. Lewis was older than his partner by almost three years and slightly round-shouldered and stooped, as if embarrassed to find himself so tall. He had a long face with dark eyes that stared at you, separated by a thin nose. His laugh when it came was unforced and hilarious, exploding uncontrollably out of his chest, a great shriek of a laugh which shook his whole body and left him completely paralyzed for minutes at a time, after which he would have to stretch out and lie on the floor, his shoulders occasionally heaving, until he gained control of himself again. A tall man, well over six feet, his thinning black hair struggling with a parting. Alex said it wasn’t a parting it was a departing, a cruel jibe, since even in his twenties his falling hair was beginning to worry him more than he cared to admit. He didn’t like things out of control, witness his tiny handwriting (“Ooh look, a mouse left me a note,” Alex would scream), but he could control neither his hair nor his partner. Brooding, obsessing, cynical, slightly menacing, he loomed over Alex like a headmaster.

Not that he dominated Alex. The Red Nose knows a thing or two when it comes to survival. He is by nature a bad boy, a consumer of things, a wolfer of experience, an enjoyer of the sensual. “He’s like a timorous gourmet,” Lewis said in an interview, for Alex was a consumer of women when he could, of drugs and alcohol, before they nearly killed him, and above all of food. He loved to eat. He fought a constant battle with his weight. He was by nature a wide boy, with the classic endomorphic profile. He would be much wider if his strong will to succeed didn’t force him to punish himself by running on the machine all day, beads of sweat rolling down his short sharp nose. Lewis said he was a liposuction waiting to happen. Blue eyes, wide cheekbones, with a hint of protruding chin, his hair was rusty and sprouted everywhere, on surfaces where it wasn’t strictly necessary. Lewis called him the human fur ball.

“Do you shave your shoulders?” he would ask. “Every day,” said Alex. “Want me to save a little for your head so we can knit a nice rug for it?”

Never short of a riposte, Alex. Fast as lightning. There was something in this banter that was a little uncomfortable, so on the whole, by unspoken mutual agreement, they laid off each other offstage. At least according to Carlton, upon whose extraordinarily detailed notes I rely.