The Ride of My Life (12 page)

See if you can find anybody resembling me, Rick Thorne, Steve Swope, or Dennis McCoy. This was from the night of Dennis’ bachelor party. Steve, Rick, and I chipped in to give Dennis and Paridy a three-foot-tall brass mermaid as a wedding gift. Last time I saw it, it was collecting dust in the McCoys’ basement.

This was also the tour in which Rhino introduced me to beer. I can remember slurring to Rhino, “Hey, theesh things are pretty good,” as I held aloft a frosty forty-ounce bottle of Colt 45. I can’t remember much after that. There was another incident involving beverages, Joe, and me. We’d been left alone at an apartment shared by two girls we’d met on tour. They were gone, we were bored, and so we freestyled our interior decorating skills and rearranged their entire apartment—couch in the bathroom, bed in the kitchen, houseplants in the fridge. Upon the tenants’ return, they were pretty steamed.

The temperatures that summer during some shows were insane, topping 105 degrees at a few stops on the East Coast. Between the pads, helmet, and safety gear, sweat was a constant. Meeting a couple thousand kids a day exposed me to a lot of germs that wreaked havoc on my body. I spent about a week of the tour lying down, panting like a sick dog in the back of the van while Rick and Joe rode. When I heard my name, I’d pop up and grab my bike, do a couple of airs, and then return to the sick bay. One show, I was so fevered and delirious that I passed out in the middle of a lookdown air and woke up in that position, on the ground.

It was the brainchild of West Coast concert promoter Bill Silva, who was a friend of Ron Wilkerson’s. The idea was to assemble a fistful of the best skaters and bikers, put them on a killer ramp in front of ten thousand people a night, and export that energy all over the country. It was called the Impact tour, and Swatch pumped in sponsorship dollars to make it happen. I looked forward to checking it out, but then I lucked out. Days before the tour embarked, Wilkerson broke his ankle, and they needed a replacement. I was all over it and hopped a flight to Southern California. The team had been practicing their complicated choreography for three weeks, but I missed all that and arrived just in time for the opening show. “Tell me when to ride,” I asked. The debut was a success, and I picked up my cues with the help of the other riders. Apparently I hadn’t missed much during practice—the ramp had been set up inside a hot warehouse in San Diego, without ventilation or air conditioning. Next door there was a crematorium, and it was close enough to cough on the smoke that puffed out of the chimney—yuck.

Impact was the first large-scale production in action sports, and the first time that many bikers and skaters shared a ramp on tour. The ramp was thirty-six feet wide and ten feet tall and constructed of metal. Blyther, Wilkerson (from the sidelines), and I were the two-wheeled contingent. The skaters included Chris Miller, Jeff Phillips, Mark “Gator” Rogowski, (who in the ninties changed his last name to Anthony) Kevin Staab, and rollerskater Jimi Scott. We got treated like stars—decent hotels, custom leather jackets for “the talent,” catered food, after parties, and plenty of interviews from local radio, TV, and newspapers. A semi truck pulled the ramp and equipment, and a crew set everything up at each sports arena we played. We traveled in style via a posh tour bus-

and at first everybody was stoked to find out it had just been used by a popular metal band on tour. A few days into the tour, however, some of the guys noticed their crotches were on fire—leftover presents from the band: crabs in the beds. Sheets were tossed, mattresses were sanitized, and underwear was jettisoned.

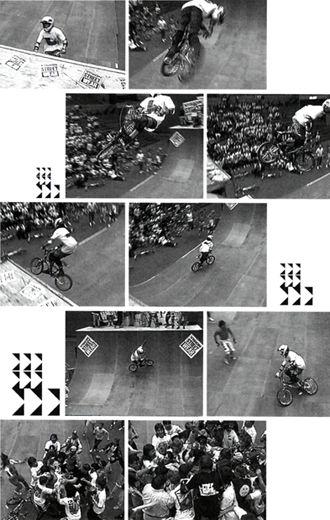

Each show was choreographed and went like this: A short film played on a jumbo monitor above the stage and individually introduced the athletes. We’d roll out onto the ramp for an introductory run, one at a time, and once we were all assembled on the decks, the music kicked in, the house lights were triggered, and all hell let loose. We dropped in and rode—doubles, triples, and even a suicide run with everybody in the production on the ramps at once. The show peaked with a heart-stopping run: The lights were off and black lights on the coping barely illuminated the ramp, and our clothing, bikes, and boards had just enough bright highlights to makes us visible. It was freaky. Then the lights came on, and we did a five-minute-long doubles and triples run linked with all talent dropping in on different walls and keeping the airs flowing over, under, and around each other. It was super techy and burly.

The Impact tour was a moment of total enlightenment for me as a rider and changed my style forever. I had a philosophy that freestyle was all about control. Part of this mentality came from the early days of the sport, when riders would meticulously plan out their routines and even write a trick list down in the order each trick was to happen. After years of riding, one trick would flow into the next on autopilot. Then I saw Jeff Phillips skate. He blew me away because he was completely unpredictable—I never knew what trick he would set up until he hit the wall of the ramp. Even Jeff didn’t know what he was going to do until he was in the moment. He was totally in control, but he was equally unpredictable. It was an organic approach to vert that I loved—so much, that I threw out every preplanned run I’d programmed myself with over the years and learned to flow vert, riding it one wall at a time.

My mom and dad flew down to see the show in Dallas. They were glowing with pride when they saw the slick presentation, the pure spectacle of the event, and the riding. It was a far cry from the days of the Mountain Dew Trick Team shows from just three years prior. That was probably my favorite Impact show.

Manchester, England. This was the demo where I did the first flair. [Photograph courtesy of Mark Noble]

Shortly after the Impact tour ended, I got another chance to do some biker-skater demos. It was the last trip of the year. Wilkerson’s KOV contests had an annual invitational each year in Paris, and the top four pro and am bikers got to go. This time there was the added bonus of riding with vert skaters Tony Hawk, Mark Gonzales, Danny Way, Adrian Demain, Joe Johnson (there was a skateboarder and bike rider who shared the same name—both Joes were on this trip), and Jimi Scott. I was extramotivated to make the trip. I’d missed the previous Paris KOV, because I was out with a broken leg. All year I heard tall tales about how insane it had been.

Counting down to the departure date, I got my tickets, did my laundry, and dug my passport out. I tried to remember some of the elementary French phrases from my eighth-grade class. I couldn’t wait. Then, the day before I hopped on the plane, I couldn’t remember who I was.

I’d been riding the Ninja Ramp and came in off an air when my forks broke. I got hurled into the flat bottom headfirst and was knocked out cold for seven hours. This was probably the worst head injury I’d ever suffered riding bikes—and I was beginning to realize how burly vert riding could be. A month beforehand, Ron Wilkerson had slammed on his trademark nothing air (no-hander no-footer) on an AFA quarterpipe and was laid up in a Wichita hospital with a bad head injury for two weeks. After Ron’s condition stabilized my dad converted his plane into an air ambulance, hired a paramedic, and flew to get Ron and bring him home to San Diego. The whole time, plenty of people in the sport were holding their breath, hoping against hope that Ron would recover. He did. But it underlined the severe consequences of ramp riding, and most of the sport switched to full-face helmets just after that terrible crash.

I came down so hard on the Ninja Ramp that even though I was wearing a full-face helmet, I had amnesia for three days. Bits and pieces of my memory floated back to me, in random order. When I saw my bags packed and my plane tickets to France, I remembered I really, really wanted to go. But I couldn’t exactly remember why. I faked like I was fine and boarded my flight.

Standing on the decks of the halfpipe in Bercy stadium in the middle of Paris, I realized I was in over my head. My bell was still ringing, and I had no idea how to ride. I wasn’t even one hundred percent sure I

had

riding experience—watching Lee Reynolds, Chris Potts, and Joe Johnson (the biker) doing airs, I couldn’t believe anybody would be stupid enough to drop in and actually do airs that high. I was wearing all my gear, sitting on my bike, and shaking my head. “No

way

would I ever do that,” I told them. “You guys are going

ten feet

high.” They told me I could do thirteen. I laughed at the silliness of what they were saying. After much convincing on their part, I psyched myself up and figured I could maybe drop in, ride across the bottom, and pop out on the opposite deck. That didn’t look too hard. As soon as I entered the first tranny, my body’s muscle memory took over—my first wall I did a five-foot air, and a six-foot air on the next. Within an hour or two I got a few tricks back (my friends convinced me that I could not only do them, but that I’d invented them). It’s weird not being yourself. Very, very weird.

The best part about the Paris invitationals was that the promoters from Bicross magazine put the events together as goodwill ambassadors. They were trying to get American pros psyched on Europe. It worked. Our crew stayed in a medieval castle. We were treated to helicopter rides over the city and trips to the catacombs under the streets as well as carted up to the top of the Eiffel Tower and out to plenty of nice dinners and nightclub excursions. The trip lasted a week, and our big demo/contest was only a one-day event. The rest of the days were reserved for practice, and the nights were for playtime. We went to the Crazy Horse, the original French burlesque club that cost four hundred dollars a table and required ties to get past the doorman. Nobody in our group had ties, but Mark Gonzales emerged from the bathroom wearing a tie he made from toilet paper and quickly origamied another half-dozen to get us past the rude bouncer. Another night, breakdancing bravado was called into play.

Freestylin’

magazine’s staff photographer and fire-starter, Spike Jonze, instigated our entire posse into dance floor combat against some French B-boys, and we pulled out all the moves. It was a matter of pride, and I’m proud to say we left that Eurodisco in awe, I think. Since nobody spoke French very well, it was hard to tell if they were yelling at us in joy or anger.

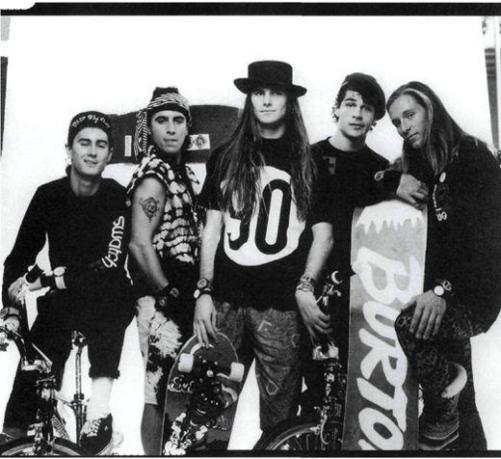

Part of the Swatch Impact Team (left to right): Brian Blyther, Mark “Gator” Rogowski, Kevin Staab, me, and Jimi Scott. (Photograph courtesy of Swatch, USA)

The big riding day started off with the KOV contest and blended into a demo. The stadium was at capacity, with about nine thousand spectators, but the French are masters of hype. They’d miced the stands and amplified the applause through the stadium sound system, making nine thousand people sound like thirty thousand. It was nuts.

In France, they knew everything there was to know about wine. Flavors were said to taste even better if the glass of grapes you were enjoying had been fermented during a particularly great year. When I returned to Oklahoma after that trip, I reflected on my collective life experiences of 1988. If I could’ve bottled everything I’d done that year… I think it would’ve made a damn fine vintage.