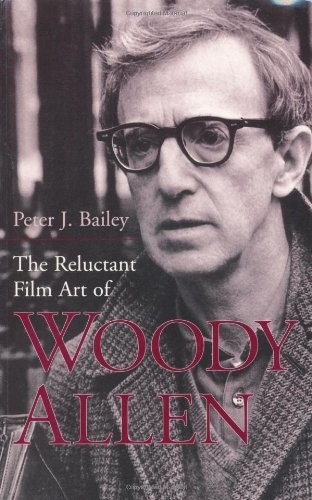

The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The Reluctant

Film Art of

WOODY

ALLEN

Peter J. Bailey

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices:

The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

12 11 10 09 08 6 5 4 3 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bailey, Peter J., 1946–

The reluctant film art of Woody Allen / Peter J. Bailey.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-10 0-8131-9041-X (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Allen, Woody–Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PN1998.3.A45 B35 2000

791.43’092–dc21 00-028308

ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-9041-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of |

For Frances Weller Bailey,

the constancy and magnitude of whose loyalty to me and to the completion of

The Reluctant Film Art

is so lacking in the depictions of wives and husbands in Woody Alien’s films as to account almost singlehandedly for so many of these movies culminating in such disheartening resolutions.

Contents

1 That Old Black Magic:

Woody Allen’s Ambivalent Artistry

2 Strictly the Movies:

Play It Again, Sam

3 Getting Serious:

The Antimimetic Emblems of

Annie Hall

4 Art and Idealization:

I’ll Fake

Manhattan

5 Strictly the Movies II:

How

Radio Days

Generated Nights at the Movies

6 Life Stand Still Here:

Interiors

Dialogue

7 In the Stardust of a Song:

Stardust Memories

8 Woody’s Mild Jewish Rose:

Broadway Danny Rose

9 The Fine Art of Living Well:

Hannah and Her Sisters

10 If You Want a Hollywood Ending:

Crimes and Misdemeanors

11 Everyone Loves Her/His Illusions:

The Purple Rose of Cairo

and

Shadows and Fog

12 Poetic License, Bullshit:

Bullets Over Broadway

13 Let’s Just Live It:

Woody Allen in the 1990s

14 Because It’s Real Difficult in Life:

Husbands and Wives

15 Rear Condo:

Manhattan Murder Mystery

16 That Voodoo That You Do So Well:

Mighty Aphrodite

17 And What a Perfect Plot:

Everyone Says I Love You

and

Zelig

18 How We Choose to Distort It:

Deconstructing Harry

19 From the Neck Up:

Another Woman

and

Celebrity

20 Allen and His Audience:

Sweet and Lowdown

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

Photofest provided the stills used in this book; Ron Mandelbaum was very helpful in making Photofest’s trove of Woodiana available to me. Thanks to St. Lawrence University for providing support for this project in the form of sabbatical leave and research grants. It has been my privilege to teach at St. Lawrence for two decades, and I owe the college administration, my faculty colleagues, and my students a debt of gratitude for jointly providing me with such a richly satisfying academic career. The manuscript for

The Reluctant Film Art

benefited from critiques generously provided by friends, colleagues, and relatives: Thomas L. Berger, Shakespearean bibliographer and owner/player/manager of the English Department football team; Jackson Cope, mentor,

amico,

and intellectual inspiration; David Shields, novelist, pop culturist, former running companion, and continuing editor and literary confidant; and Lucretia B. Yaghjian, professor of theological writing and lifelong practitioner of “acceptance, forgiveness, and love.” Frances Weller Bailey brought substantial knowledge of film technique and history to her extended critiques of the manuscript, benevolently excusing my penchant for reading the history of film as if it reached its culmination in Woody Allen movies.

The Reluctant

Film Art of

WOODY

ALLEN

1

That Old Black Magic

Woody Allen’s Ambivalent Artistry

Deconstructing Harry

opens with what is probably the raunchiest joke Woody Allen has committed to film. Ken (Richard Benjamin) and his sister-in-law, Leslie (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) are having an affair; while their respective families are down by the lake enjoying a picnic, the lovers are inside his house, copulating. Enter Leslie’s blind grandmother. “Come,” she bids Leslie, “lead me down to the lake.” Having no idea what the couple is doing, Grandma cheerfully engages Ken in a discussion of the merits of martini garnishes. He eventually achieves a clamorous orgasm, prompting Grandma to comment, “Boy, you must

really

love onions!”

The most significant element of this visual joke is that the viewer only gradually realizes that the scene is not Woody Alien’s one-liner but Harry Block’s—that it’s a visualization of a scene from his recent novel. As so often happens in Alien’s films, this projection of the protagonist’s art provokes laughs while epitomizing its maker’s personality: Harry, we will find, is as willing to sacrifice the people in his life for a laugh as he is to sacrifice his characters. In addition to exposing the character of Harry’s art (which might be described as a darkly eroticized, cynical exaggeration of Alien’s), this dramatized excerpt of Harry’s novel creates an aura of self-consciousness about the making of art, a sort of teasing artistic self-referentiality never completely absent from Allen’s films. The likelihood that this mediation effectively absolves Allen of the gag’s crudity by transferring culpability to a fictional novelist is small: so unrelenting is

Deconstructing Harry’s

indictment of artists that Allen can’t help tarring himself with his film’s unsparing brush.

Deconstructing Harry,

he told John Lahr while shooting the film, is “about a nasty, shallow, superficial, sexually obsessed guy. I’m sure that everybody will think—I know this going in—that it’s me.”

1

Alien’s purpose was to insist that Harry is not him, but as the film’s incriminations accumulate against this artist who, by his own admission, doesn’t “care about the real world” but cares “only about the world of fiction,” the viewer’s confidence in the absolute distinction between screenwriter/director Allen and his novelist/protagonist precipitously declines. A film about an author who literarily cannibalizes his life and heedlessly exploits his friends and lovers for material for fiction constitutes dubious testimony for the incommensurability of life and art.

The earliest of the movie’s many accusations of literary exploitation against Harry is delivered by Lucy (Judy Davis), a former sister-in-law of Harry’s upon whom he has modeled Leslie and with whom he’s had a now-terminated lusty affair. Brandishing Harry’s just-published novel, Lucy arrives at his apartment in a rage. “You’re so self-engrossed, you don’t give a shit who you destroy,” she rants at him. “You didn’t care enough to disguise anything.”

“It was loosely based on us,” Harry objects, sounding remarkably like Allen defending his screenplay for

Husbands and Wives

,

2

but Lucy won’t be mollified: “I was there—I know how loosely based it was … And now, two years [after our affair’s ending], your latest magnum opus emerges from this sewer of an apartment where you take everyone’s suffering and turn it into gold, into literary gold. You take everyone’s misery—you even cause them misery—and mix your fucking alchemy and turn it into gold, like some sort of black magician.”

3

Lucy’s denunciation has two things in common with the numerous other impeachments of art and artists pervading Alien’s films. Her description of his art as a form of black magic aligns her critique with the numerous Allen movies—

Shadows and Fog

being the most obvious—in which art is allegorically configured as a form of magic act. Additionally, her charge that Harry’s fiction “spins gold out of human misery” invokes the necessary parasitism of art upon life, the quality of aesthetic vampirism dramatized in the fictional authorial self-incriminations of Philip Roth (

The Counterlife

and

Operation Shylock

)

4

and in Raymond Carver’s “Intimacy.”

5

Deconstructing Harry

intentionally inflates the corruptness of artist Harry Block for comic effect; nonetheless, the film constitutes a fully appropriate coda for Allen’s career precisely because of its extravagantly exaggerated censure of a life dedicated to and obsessed with art. The most unequivocally peevish of Allen’s depictions of artists,

Deconstructing Harry

represents less a new direction for Allen than a concentrated dramatic reprisal of his previous film’s indictments against them.