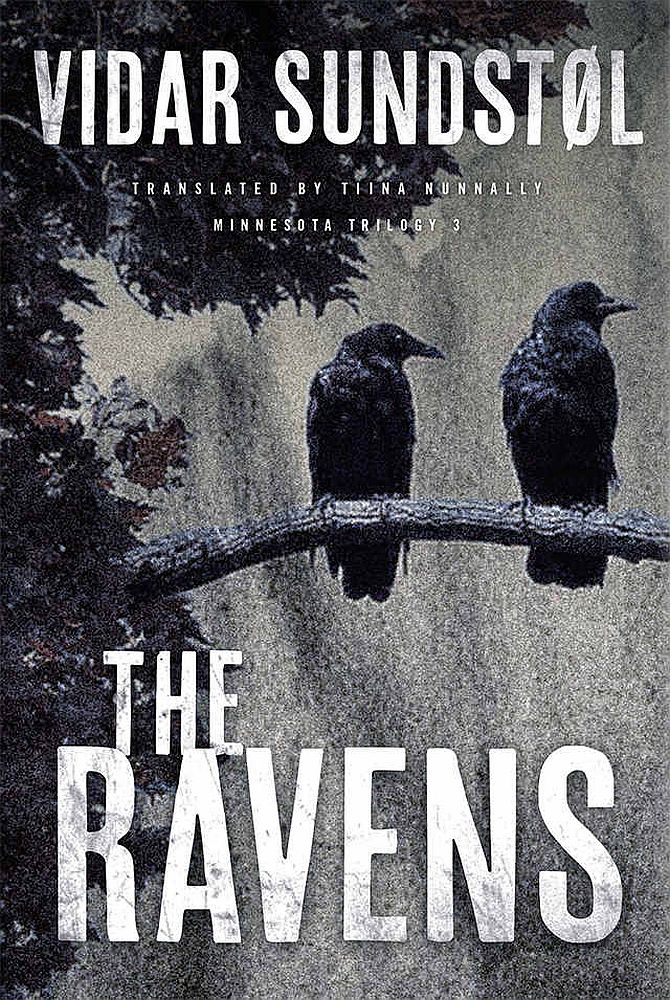

The Ravens

Authors: Vidar Sundstøl

Minnesota Trilogy

The Land of Dreams

Only the Dead

The Ravens

Vidar Sundstøl

Translated by Tiina Nunnally

Minnesota Trilogy 3

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA (Norwegian Literature Abroad, Fiction and Nonfiction).

Copyright 2011 by Tiden Norsk Forlag, Oslo, an imprint of Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS. Originally published in Norwegian as

Ravnene.

English translation copyright 2015 by Tiina Nunnally All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis, MN 55401–2520

LIBRARY

OF

CONGRESS

CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION

DATA

Sundstøl, Vidar.

[Ravnene. English]

The Ravens / Vidar Sundstøl ; translated by Tiina Nunnally.

ISBN

978-1-4529-4473-9

1. Murder—Investigation—Fiction. 2. Family secrets—Fiction. 3. Brothers—Fiction. 4. Minnesota—Fiction. 5. Mystery fiction. I. Nunnally, Tiina, translator. II. Title.

PT8952.29.U53R3813 2015 839.823'8—dc23 2015000051

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

LAKE

SUPERIOR

had frozen over and was transformed into a desolate white wasteland. In Duluth the temperature hovered at a steady twenty below. No ships passed under the old Aerial Lift Bridge, although normally that would have happened several times a day. Now the bridge remained motionless all day long as the low January sun glinted off the frost-covered steel.

Inga Hansen was knitting. Only the faint clacking of her knitting needles disturbed the silence. From the walls stared so many faces from her long life: her husband wearing his police uniform, the two of them in their wedding picture, her grandchildren at various ages, her sons in high school photos. One picture showed a group of dark-clad people, maybe thirty or forty in all, both adults and children, formally posed for the photograph taken on the deck of a ship. Behind them steam rose up from the smokestack. In the bottom right-hand corner someone had written, “Duluth, October 3, 1902.” In among the solemn-looking crowd were two young people who would become Inga’s grandparents—a fact that almost brought her to tears whenever she thought about it. This was a response that had gradually emerged over the years. In the past she’d been able to bear anything at all without shedding a single tear. Nowadays it took very little to make her cry.

She looked at the newest photo of her granddaughter, Chrissy. With her neatly brushed blond hair forming a halo around her

head, she looked like an angel, Inga thought. But Chrissy hadn’t come to visit in a long time. Truth be told, they hadn’t seen each other in over a year, although they’d talked on the phone a few times. No doubt that was what happened when kids became teenagers; suddenly there were things that were far more interesting than grandmothers. Even so, Inga had decided that the green-and-white scarf taking shape under her never-idle hands would be a birthday gift for Chrissy when she turned eighteen.

On the slope below the nursing home the houses and yards were covered with a blanket of snow. High overhead was the pale blue vault of the sky, looking as it had every day for nearly a month. And stretching out beneath it like the marble floor of a vast cathedral was the lake, once again frozen over. She couldn’t look for very long at the white surface that extended eastward until it merged with the sky; the sight hurt her eyes. And she found it alarming that the entire lake looked exactly the same. So she tried not to dwell on it, although occasionally the thought would slip into her mind, unnoticed, until she suddenly pictured a place so far away that there was no land in sight in any direction; nothing but a dazzling whiteness with no shadows, because there was nothing out there that might cast a shadow. Yet the worst was imagining the total lack of sound. She imagined a piercing silence.

Someone was knocking on the door. Quickly she set down her knitting and smoothed out her skirt.

“Come in!”

One of the staff members opened the door.

“Hi, Inga. Postcard for you,” she said, stepping into the room and holding out the postcard, as if it were a major event for someone to be writing to Inga Hansen.

“Is that all?” asked Inga.

“Yes. But it’s nice to get a card in the mail, don’t you think?”

Inga smiled politely as she set the card down without much interest. But as soon as the door closed, she picked up the postcard and eagerly read what it said.

“Oslo, Norway” was printed diagonally in big white letters across a nighttime scene showing a street decorated for Christmas. She turned the card over and read the few lines written in the familiar script.

Dear Mom—

Having a good time in the “old country.” Staying at another hotel now, it’s a little cheaper. Haven’t yet made it to Halsnøy but of course I will soon. The Norwegians are nice, polite people, as you can imagine. Won’t be home for a while yet. It’s really cold here! Happy New Year, and say hello to everybody.

Lance

The postmark showed that the card had been sent from Oslo on January 17, which was five days ago. The two other cards she’d received from her son had also been sent from there. It was back in November, right after the deer hunt, that he’d phoned to tell her he was going to Norway. She was glad that he’d decided to do something different for a change. Otherwise he spent all his free time immersed in those history archives of his.

Inga turned the card over again to look at the picture on the front. A long street gently sloping up toward a building painted yellow with a flag flying from the roof. The street was crowded with people. It was possible that some of them might even be relatives of hers. She liked that idea. There they were, her relatives, and all of them spoke Norwegian, just like her grandparents and the rest of the immigrants in the photograph taken on board the steamship in Duluth on that October day in 1902. When she was a child, she sometimes heard her grandparents speaking their native language to each other. She almost thought she could hear all those people on the street decorated for Christmas on the postcard. All those Norwegian voices humming on a winter evening in Oslo, where her son Lance was also walking around.

Inga put down the card and picked up her knitting. She couldn’t sit idle for long if she was going to finish the green-and-white scarf in time for Chrissy’s birthday.

Yet she soon found herself thinking again about the ice-covered lake, and she felt a shiver pass through her.

HE

LUNGED

OUT

OF

BED,

striking his head so hard on the floor that flames shot up in the back of his eyes, and he tore at his pajama top, sending several buttons flying. It was pitch dark in the room, and he was dying. His breath had stopped somewhere between his lungs and his mouth, like an elevator stuck between floors. Desperately he began flailing around in the dark, trying to make something happen, although he didn’t know what that might be. Nothing was certain anymore except that he didn’t have long to live. His hand touched something that fell to the floor with a bang and shattered into pieces. He inhaled with a gasp, as if suddenly returning to the surface after making a lengthy dive. He greedily drew in great quantities of air, noticing how the paralyzing fear slowly released its hold on his body. Maybe he wasn’t going to die after all.

With trembling arms and legs he hauled himself into a sitting position on the edge of the bed and turned on the lamp on the nightstand. His pajama top hung open, without a single button. His big white stomach gleamed in the faint glow of the lamp. Fear was still circulating through the room like electrical pulses, or like arrows shot from bows by thousands of little demons that had descended upon him as he slept. A sob suddenly filled his throat like a cork; it felt so tight that he didn’t even dare swallow. He knew that under the painful cork was a bottomless reservoir

of self-pity, and right now he was close to giving in to it, but he refused.

Anything but a nervous breakdown, thought Lance Hansen.

He stood up, still on the verge of tears, and caught sight of himself in the mirror. A fat, middle-aged man with tearful eyes, a white whale living in total isolation in a hotel room in a foreign country. The next moment he was over at the desk, swinging his right arm like a sledgehammer and slamming his fist down on the surface, sending scraps of food skittering across the floor. A beastly howl echoed through the room, and the jolt of pain reverberated all the way up to his shoulder, but he didn’t give a shit. Again he pounded the desk with his leaden fist, this time splintering the wood. Oh, how good that felt! Lance turned around and jabbed the air with several left-right combinations, like a boxer just before a fight, throwing swift punches that would have knocked anybody out cold. “That’s enough!” he shouted. “I won’t stand for this anymore!”

HE

MUST

HAVE

FALLEN

ASLEEP

AGAIN,

and when he woke, there was no longer anything wrong with his breathing. He took a shower, got dressed, and went downstairs to the small room where breakfast was served. But he found no food and no people. The hotel seemed dead, and his footsteps echoed along the empty hallways as he went back to his room. He checked his watch, which he’d left on the nightstand. It was 5:10 in the morning.

Lance was ravenous and desperate for a cup of coffee, but it would be almost half an hour before he could get breakfast, and nowhere else was open this early. So he really had no choice but to undress and go back to bed, although he really didn’t want to. He wanted breakfast and some strong coffee. Resigned, he sat down at the desk and looked inside the carton from yesterday’s Chinese takeout. There was still a little food left. He used his fingers to stuff his mouth with the cold rice and sauce that had now congealed like butter. Then he remembered that several days ago he’d put a couple of rolls in one of the desk drawers. He had intended to eat them with dinner, but then forgot. He pulled out

the drawer, and there were the rolls along with the old diary written by his grandmother Nanette. That had been one of the first things he’d packed when he decided to make this trip. The book was over a hundred and twenty years old and written in French. Inside were two sheets of paper with an English translation of a few pages. Lance ran his finger over the worn binding; it was so soft that it was almost like touching living flesh. The diary and the two sheets of paper contained quite a number of truths about him. That was probably why he’d brought them along when he left—to remind himself, here in this foreign land, of who he was and where he came from.

Lance closed the drawer and placed the two rolls on the desk. With his fingertip he poked at one of them. The roll was hard as a rock, but when he broke it in half, the bread was still edible; only the crust was too hard. After devouring the insides of both rolls, he finished off the meal with a couple of glasses of water from the tap. Then he began packing his suitcase.