The Rags of Time (24 page)

Authors: Maureen Howard

Imagine there’s no Heaven

It’s easy if you try . . .

It’s easy if you try . . .

Down the slope to Strawberry Fields, NYPD reads the

Post.

Post.

It’s Armistice Day. No mixed emotions. My father wore the poppy in his buttonhole but would not march. Something about the pomp after the circumstances he’d seen in France; and you’ve never told me why you trusted the sodden parachute that sucked you down. There were alligators and the scum of algae in Florida’s warm waters, never told your air force career as a terrifying story. Last year a vet home from Iraq stood by the memorial in the corner park just down from our little house in the country. Veterans Day, we now call it. He spoke of his friends, those left behind, shuffling through his words, not attempting eloquence, while old vets in their overseas caps and scraps of uniform buttoned over the bulge stood at attention. Then Taps, truly moving, followed by the ear-shattering salute that made the babies cry.

Daybook, Thursday, November 18There will be a water shutdown from 10AM until 4PM in the CD line. Please make sure all taps are closed. We are sorry for the inconvenience.

Old pipes give out now and then, don’t I know. I draw water in the pasta pot and big salad bowl, laundry day in the village. Almost immediately I’m thirsty. I drink from the brass dipper that hangs on the kitchen wall, a decorative item. Thirst quenched, our lives are too easy, don’t we know.

Meditation and water are wedded forever.

Ishmael, about to go on his journey in Melville’s big book that would succeed, though not in his time. I haven’t the heart, literally, or mind for meditation. In this arid world, the waves lapping against the shore of the Reservoir may be too gentle, the still mirror of the Lake cold, unreflecting.

The November of my soul.

Meditation and water are wedded forever.

Ishmael, about to go on his journey in Melville’s big book that would succeed, though not in his time. I haven’t the heart, literally, or mind for meditation. In this arid world, the waves lapping against the shore of the Reservoir may be too gentle, the still mirror of the Lake cold, unreflecting.

The November of my soul.

So, in the parched season at the El Dorado, I’ll stay home as you once again advised. Oh, the familiar warning was in your voice as you put on your wool cap.

Don’t venture.

That’s how you put it, no need to say more.

That’s how you put it, no need to say more.

Heart pumps a heavy beat. Ankles and wrists swollen, shipping water. My vials of medication, sleepless nights, heavy rain against the kitchen window advise against panning for choice nuggets in the Park today. So it’s follow the yellow brick path, stake my claim in El Dorado. For Columbus there was no gold, only the discovery of parrots, pumpkin seeds, cinnamon bark, the useless glisten of mica and the trade-off of measles for syphilis—until the third voyage. At last, a gritty find up the Orinoco. By then Christoforo was out of favor. He believed in El Dorado, the name of an island where a gilded man rose from the river once a year. As though to sustain his belief in Christ and the Madonna, he honored the story of a god never seen.

This day, in a tower that’s lost the legend for which it was named, I am confined with my books to take up this endgame of discovering where I am in the world—not Kansas, not Bridgeport. An outlander, I arrived in this city in my college kilt and polo coat fifty-five years ago. You understand that the Park will always be new territory under my surveillance; not so for the kids in the playground, not for you, city boy. So my archives: tinted postcard of Bethesda Fountain, a clipping from the

Times

flaky at the edges—John Paul II blessing the adoring crowd through safety glass of the Popemobile, bird lore aplenty, a sepia photo of real sheep in the Sheep Meadow, shots of the young guys from your office playing softball, Nick’s birthday piñata spilling its treasures in the Pinetum, and

The Gates

of 2005, their citrus grandeur flying free of critical commentary, General Sherman gilded anew, and you, misty-eyed on the Great Lawn cheering

Nessun dorma . . . O Principessa

, holding my hand when Pavarotti hit high C. Who took the picture?

Times

flaky at the edges—John Paul II blessing the adoring crowd through safety glass of the Popemobile, bird lore aplenty, a sepia photo of real sheep in the Sheep Meadow, shots of the young guys from your office playing softball, Nick’s birthday piñata spilling its treasures in the Pinetum, and

The Gates

of 2005, their citrus grandeur flying free of critical commentary, General Sherman gilded anew, and you, misty-eyed on the Great Lawn cheering

Nessun dorma . . . O Principessa

, holding my hand when Pavarotti hit high C. Who took the picture?

You will know at once that all views and encounters are true as the arc of the Bow Bridge though carefully engineered as a cascade in the Ramble, inevitable as statues along the way. I will never, under oath, convert the Park to an attic or yard sale for the El Dorado, just file the cache of mementos as travel stories, tickets for safe passage to the end of my days. When I make the call, isn’t that how you do it? No investment too big or too small.

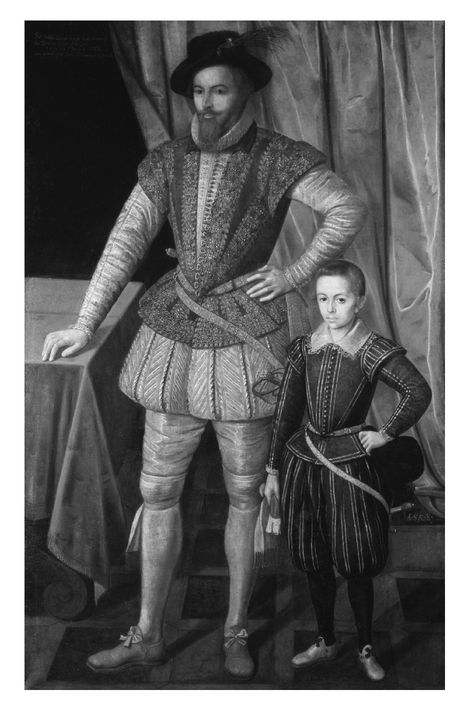

THE HISTORY OF THE WORLDLike Sir Walter Raleigh, who packed a trunk of books when he went to sea, I depend on books in my back room—too often, you say. Land-locked, I could never invent Raleigh’s bogus search for El Dorado, or predict his downfall having betrayed the Virgin Queen by loving a maid. His story often told between scholars’ covers and popular bios with portraits of the great courtier himself, pearls sewn into his weskit, gilt buttons, Orders of Merit. And here’s the heartbreaker in silk stockings, a Gentleman of the Crown with his son Wat, dwarfed by Dad’s glory. A girl would easily lose her heart to Sir Walter’s bright eye, the curl of his rusty beard, but the Queen’s Maids of Honor were never to marry. Too many books in my cell: I take down

Aubrey’s Brief Lives

(c. 1692) in which the gossipy biographer gives Shakespeare short notice, though he’s enchanted at some length by Raleigh’s amorous adventure.

Aubrey’s Brief Lives

(c. 1692) in which the gossipy biographer gives Shakespeare short notice, though he’s enchanted at some length by Raleigh’s amorous adventure.

He loved a wench well; and one time getting up one of the Mayds of Honour against a tree in a Wood (’twas his first lady) who seemed at first to be somewhat fearful of her honour, and modest, she cryed, sweet Sir Walter, what doe you me ask? Will you undoe me? Nay, sweet Sir Walter! Sweet Sir Walter! Sir Walter! At last, as the danger and the pleasure at the same time grew higher, she cryed in the extasey, Swisser Swatter Swisser Swatter. She proved with child, and I doubt not but this Hero took care of them both, as also that the Product was more than an ordinary mortal.

About the Product, more later.

In

The Loss of El Dorado,

Sir Vidia Naipaul sifts through Raleigh’s

The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana, With a relation of the great and Golden Citie of Manoa (which the Spanyards call El Dorado) And of the Provinces of Emeria, Arromaia, Amapaia, and other Countries with their rivers, adjoining. Performed in the year 1595. by Sir W. Ralegh Knight, Captaine of her Majesties Guard, Warden of the Stanneries, and Her Highnesse Lieutenant Genrall of the Countie of Cornwell,

to declare the book

part of the world’s romanc

e and its details

fatally imprecise

. Like Raleigh’s first readers, I’m charmed while I mistrust the writer of

The Discoverie

but will testify that he threw his cloak down on a puddle so the Queen might not muddy her royal shoes. How did this story of gallantry find its way to the lower grades of a working-class Catholic school in the last century? It was said by Sister Philomena that Raleigh may have been of the Catholic faith! A shy woman, fingers fumbling with her rosary when the Monsignor came to bless us once a year. Movies have made much of Sir Walter romancing the Queen (best Tudor pick, an unleashed Bette Davis in

Elizabeth and Essex,

’39, in which Raleigh is demoted to an ex). Fool’s gold in the Hollywood Hills, or on the banks of the Liffey:

The Loss of El Dorado,

Sir Vidia Naipaul sifts through Raleigh’s

The Discoverie of the Large, Rich, and Bewtiful Empyre of Guiana, With a relation of the great and Golden Citie of Manoa (which the Spanyards call El Dorado) And of the Provinces of Emeria, Arromaia, Amapaia, and other Countries with their rivers, adjoining. Performed in the year 1595. by Sir W. Ralegh Knight, Captaine of her Majesties Guard, Warden of the Stanneries, and Her Highnesse Lieutenant Genrall of the Countie of Cornwell,

to declare the book

part of the world’s romanc

e and its details

fatally imprecise

. Like Raleigh’s first readers, I’m charmed while I mistrust the writer of

The Discoverie

but will testify that he threw his cloak down on a puddle so the Queen might not muddy her royal shoes. How did this story of gallantry find its way to the lower grades of a working-class Catholic school in the last century? It was said by Sister Philomena that Raleigh may have been of the Catholic faith! A shy woman, fingers fumbling with her rosary when the Monsignor came to bless us once a year. Movies have made much of Sir Walter romancing the Queen (best Tudor pick, an unleashed Bette Davis in

Elizabeth and Essex,

’39, in which Raleigh is demoted to an ex). Fool’s gold in the Hollywood Hills, or on the banks of the Liffey:

Sir Walter Raleigh, when they arrested him, had half a million francs on his back including a pair of fancy stays. The gombeenwoman Eliza Tudor had underlinen enough to vie with her of Sheba. Twenty years he dallied there between conjugal love and its chaste delights and scortatory love and its foul pleasures.

—Stephen Dedalus, June 16, 1904

In the books, it’s a real estate nightmare; Raleigh’s lordly house and estates awarded to him were now swept away, his many titles and privileges discounted. He had written clever sonnets, failed at setting up the colonial settlement in Virginia, introduced the potato to Ireland, deported the Irish as slaves to the West Indies; then, to patch a tattered reputation, he set sail with a hundred Englishmen to discover the place called El Dorado. How does a life so documented become a costume drama? A naïve question you’d say, but you’re not here to keep me in line, manage the facts. Sir Walter’s legend outwits history.

Godlike in naming the new world, he embellished the many pages of

The Discoverie

with maps of mountains and rivers, the exotic customs of each stop along his way in the Empyre, titles of tribes, names of chieftains. He returned with the glitter of marquisate in worthless schist to ornament his big book with authenticity, most particularly when reporting the wonders of Manoa, a city never seen.

And if Peru had so many heaps of Golde, whereof those Ingas were Princes, and that they delighted so much therein, no doubt but this which nowe liveth and raineth in Manoa, hath the same humor, and I am assured hath more abundance of Golde, within his territorie, than all Peru, and the west Indies.

Writing his way out of failure, his account is hearsay of a crystal city, rumor that a secret door in the side of a mountain, when opened, would reveal the treasures of El Dorado. War had depleted the Queen’s coffers. Sound familiar? Ordered to bring back gold, he had only a book writ out in a bold bluff of words. That there might be little or no gold was contemplated before he set sail: the report of his Caribbean adventure would then be worse than a lie, a fiction. He lived in disgrace, though not for writing his

Discoverie,

a best seller. The Faerie Queen—bloodless in old age, blanched as we see her on-screen—

passed,

as we now say. The Elizabethan world over, the Stuarts were now free to find cause. King James committed Raleigh to the Bloody Tower on a conspiracy charge long delayed. Sir Walter collaborating with the Spanish! Not likely. Confined in comfort, he turned to the possible certainties of science. Something like a gentlemen’s club in the Tower: poets dropped by for a visit; chemists worked their experiments in half-light cast through narrow windows. Aubrey tells us that here the mathematician Hariot wrote to Johannes Kepler on the refraction of light, solving the mystery of rainbows. Lady Raleigh lived comfortably with her husband, Wat, and their servants. The prisoner wore elegant cloaks, lace ruff at his throat. By a little shed next to his garden, he worked on his herbal elixirs and the desalination of seawater. In this pleasant confinement, he wrote

The History of the World

; how’s that for reach? Can we understand that in the entanglement of what was now Jacobean politics, the King demoted Walter to schoolteacher, sent his son to be tutored by his prisoner?

The History

was in part a textbook for Prince Henry, who loved working with Walter, did not love his father. Imagine the young prince leaving the great world of the Court for the Tower to read along with the scholar who began his course with the Creation, proceeded ever onward, invoking the wisdom of Aristotle, Virgil, Sir Francis Bacon. The myth maker Ovid, of course. Yes, Sister Philomena, Sts. Paul and Augustine were among those called upon to verify Raleigh’s version of First Days, which has a geography beyond our schoolroom imagination, as in a chapter:

That Paradise was not the whole earth, as some have thought, making the ocean to be the fountain of four rivers.

Mapping Eden, spinning the globe, sweeping the ancient nations of the world into the timeline of each day’s lesson. Turn back and you will find politics in the Preface. A pair, these two, Prince and tutor devoted to the stories that give the lie to the Divine Right of Kings, to the very King, Henry’s father, who was the historian’s jailer. While the other boy, Wat, took himself off, attempting to get bloodied as a soldier in imitation of his father.

The Historie of the World

ends in 168 BC, long after the expulsion from Paradise, the waters parting, the Flood, the glory that was Rome, though before Cleopatra put the asp to her wrist, before the year of our Lord, before the destruction of the great Library of Alexandria, before St. Anselm proposed his ingenious proof of the existence of God. We may wonder, plying our search engines, how Walter knew so many stories—of Egypt and Macedonia, the Golden Fleece, the trials of Ulysses. He’d been to Oxford, ever bookish, don’t you know? But that doesn’t answer the question how he proposed that the

Ark rested upon some of the Hills of Armenia,

or

How the Romans were Dreadful to All Kings.

He borrowed heavily from the library of the great antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton. We can imagine the couriers toting these precious volumes from Westminster to the Tower; even presume that Cotton

assisted

in the writing as did Thomas Hariot, and of equal merit, a clergyman, Dr. Burrel.

All, or the greatest part of the drudgery of Sir Walter’s History, Criticisms, Chronology, and reading Greek and Hebrew authors, were performed by him for Sir Walter

. . . so says Benjamin Disraeli in a spirited debunking of the encyclopedic work which bears neither footnotes nor acknowledgments; copyright four centuries down the lane, but we need not speculate about

The Historie of the World

ending abruptly. The Prince, gone swimming—just a boy skipping school—drowned in the polluted waters of the Thames. The tutor’s job ended. History came to its close, a provoked and provoking entry in the new book culture, another best seller for Walter.

The Discoverie

with maps of mountains and rivers, the exotic customs of each stop along his way in the Empyre, titles of tribes, names of chieftains. He returned with the glitter of marquisate in worthless schist to ornament his big book with authenticity, most particularly when reporting the wonders of Manoa, a city never seen.

And if Peru had so many heaps of Golde, whereof those Ingas were Princes, and that they delighted so much therein, no doubt but this which nowe liveth and raineth in Manoa, hath the same humor, and I am assured hath more abundance of Golde, within his territorie, than all Peru, and the west Indies.

Writing his way out of failure, his account is hearsay of a crystal city, rumor that a secret door in the side of a mountain, when opened, would reveal the treasures of El Dorado. War had depleted the Queen’s coffers. Sound familiar? Ordered to bring back gold, he had only a book writ out in a bold bluff of words. That there might be little or no gold was contemplated before he set sail: the report of his Caribbean adventure would then be worse than a lie, a fiction. He lived in disgrace, though not for writing his

Discoverie,

a best seller. The Faerie Queen—bloodless in old age, blanched as we see her on-screen—

passed,

as we now say. The Elizabethan world over, the Stuarts were now free to find cause. King James committed Raleigh to the Bloody Tower on a conspiracy charge long delayed. Sir Walter collaborating with the Spanish! Not likely. Confined in comfort, he turned to the possible certainties of science. Something like a gentlemen’s club in the Tower: poets dropped by for a visit; chemists worked their experiments in half-light cast through narrow windows. Aubrey tells us that here the mathematician Hariot wrote to Johannes Kepler on the refraction of light, solving the mystery of rainbows. Lady Raleigh lived comfortably with her husband, Wat, and their servants. The prisoner wore elegant cloaks, lace ruff at his throat. By a little shed next to his garden, he worked on his herbal elixirs and the desalination of seawater. In this pleasant confinement, he wrote

The History of the World

; how’s that for reach? Can we understand that in the entanglement of what was now Jacobean politics, the King demoted Walter to schoolteacher, sent his son to be tutored by his prisoner?

The History

was in part a textbook for Prince Henry, who loved working with Walter, did not love his father. Imagine the young prince leaving the great world of the Court for the Tower to read along with the scholar who began his course with the Creation, proceeded ever onward, invoking the wisdom of Aristotle, Virgil, Sir Francis Bacon. The myth maker Ovid, of course. Yes, Sister Philomena, Sts. Paul and Augustine were among those called upon to verify Raleigh’s version of First Days, which has a geography beyond our schoolroom imagination, as in a chapter:

That Paradise was not the whole earth, as some have thought, making the ocean to be the fountain of four rivers.

Mapping Eden, spinning the globe, sweeping the ancient nations of the world into the timeline of each day’s lesson. Turn back and you will find politics in the Preface. A pair, these two, Prince and tutor devoted to the stories that give the lie to the Divine Right of Kings, to the very King, Henry’s father, who was the historian’s jailer. While the other boy, Wat, took himself off, attempting to get bloodied as a soldier in imitation of his father.

The Historie of the World

ends in 168 BC, long after the expulsion from Paradise, the waters parting, the Flood, the glory that was Rome, though before Cleopatra put the asp to her wrist, before the year of our Lord, before the destruction of the great Library of Alexandria, before St. Anselm proposed his ingenious proof of the existence of God. We may wonder, plying our search engines, how Walter knew so many stories—of Egypt and Macedonia, the Golden Fleece, the trials of Ulysses. He’d been to Oxford, ever bookish, don’t you know? But that doesn’t answer the question how he proposed that the

Ark rested upon some of the Hills of Armenia,

or

How the Romans were Dreadful to All Kings.

He borrowed heavily from the library of the great antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton. We can imagine the couriers toting these precious volumes from Westminster to the Tower; even presume that Cotton

assisted

in the writing as did Thomas Hariot, and of equal merit, a clergyman, Dr. Burrel.

All, or the greatest part of the drudgery of Sir Walter’s History, Criticisms, Chronology, and reading Greek and Hebrew authors, were performed by him for Sir Walter

. . . so says Benjamin Disraeli in a spirited debunking of the encyclopedic work which bears neither footnotes nor acknowledgments; copyright four centuries down the lane, but we need not speculate about

The Historie of the World

ending abruptly. The Prince, gone swimming—just a boy skipping school—drowned in the polluted waters of the Thames. The tutor’s job ended. History came to its close, a provoked and provoking entry in the new book culture, another best seller for Walter.

Other books

The Pleasure Chateau: The Omnibus by Jeremy Reed

Written in the Blood by Stephen Lloyd Jones

11 by Kylie Brant

Losing It: A Collection of VCards by Nikki Jefford, Heather Hildenbrand, Bethany Lopez, Kristina Circelli, S. M. Boyce, K. A. Last, Julia Crane, Tish Thawer, Ednah Walters, Melissa Haag, S. T. Bende, Stacey Wallace Benefiel, Tamara Rose Blodgett, Helen Boswell, Alexia Purdy, Julie Prestsater, Misty Provencher, Ginger Scott, Amy Miles, A. O. Peart, Milda Harris, M. R. Polish

Bones of Paris (9780345531773) by King, Laurie R.

Journeys with My Mother by Halina Rubin

My Heart's Beat (Hard Love & Dark Rock #2) by Ashley Grace

American Girl On Saturn by Nikki Godwin

The Three Evangelists by Fred Vargas