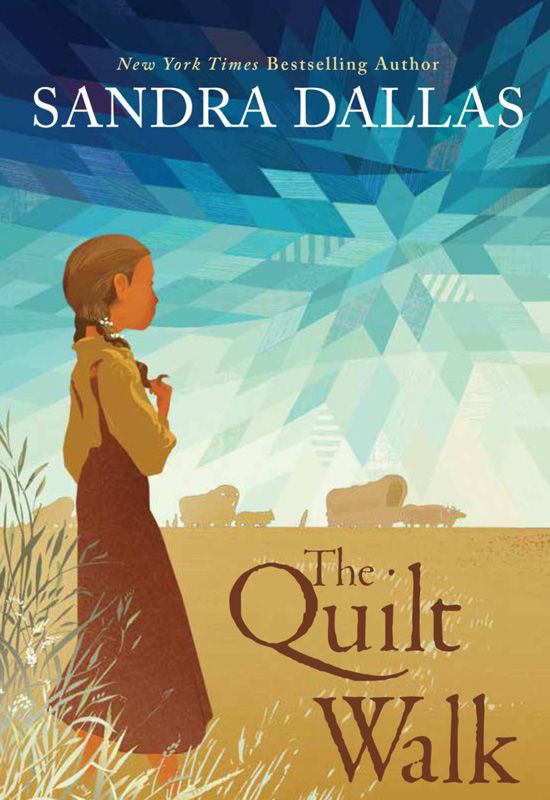

The Quilt Walk

Authors: Sandra Dallas

The

Quilt

Walk

By Sandra Dallas

PUBLISHED BY SLEEPING BEAR PRESS

TM

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are

either products of the author’s imagination or, if real, are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2012 Sandra Dallas

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted,

or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic,

electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording,

without prior written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dallas, Sandra.

The quilt walk / by Sandra Dallas.

p. cm.

Based on a story in The quilt that walked to Golden.

Summary: Ten-year-old Emmy Blue learns the true meaning

of friendship—and how to quilt—while making a harrowing wagon

journey from Illinois to Colorado with her family in the 1860s.

[1. Wagon trains—Fiction. 2. Frontier and pioneer life—Fiction. 3.

Quilting—Fiction. 4. Friendship—Fiction.] I. Dallas, Sandra.

Quilt that walked to Golden. II. Title.

PZ7.D1644Qu 2012

[Fic]—dc23

2012005863

ISBN 978-1-58536-800-6 (case)

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book was typeset in Sabon and Chanson d’Amour

Cover design by Mick Wiggins

Printed in the United States.

Sleeping Bear Press

TM

315 East Eisenhower Parkway, Suite 200

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108

visit us at

www.sleepingbearpress.com

For Forrest, our “Golden” boy

CONTENTS

THE QUILT THAT WALKED TO GOLDEN

Chapter One

WE ARE GOING WEST

W

e are going to Colorado!

Pa told us. He just came home from his first trip to Colorado Territory and announced that he and Ma and I were moving west to strike it rich.

Pa was gone almost a year. Gold had been discovered in the Rocky Mountains back in 1858, and four years after that, my pa, Thomas Hatchett, had gone off to find himself a mine. He’d promised to come home with a wheelbarrow full of nuggets. He didn’t come back with any nuggets. He didn’t even bring back a wheelbarrow. Instead he brought us the news that we were moving half across the country.

“We’re moving where?” Ma asked.

“To Golden,” Pa answered. “It’s a town at the edge of the Colorado Mountains, a booming place where we’ll make a pot of money, Meggie.” Ma’s real name was Margaret, but everybody called her Meggie.

“Are there gold mines in Golden?”

“No, Meggie. The mines are in the mountains,” Pa replied. “In Golden, the miners need places to buy their picks and shovels and gold pans, and to get their food supplies before they head off to the mountains. That means Golden will need stores, hotels, restaurants, offices, and banks. These businesses need someplace to set up. Golden is as bustling a place as you ever saw. I propose to build a business block. I’ll make a fortune from ‘mining the miners.’ I’m going to load a wagon with construction supplies, and we’ll go to Golden.”

“By ourselves?” Ma sat down in her kitchen rocker, and I perched on the footstool.

“Not by ourselves. Will’s coming, too.” Will was Pa’s brother.

“And Catherine? Did she agree to go?”

“Catherine is a dutiful wife,” Pa said. “She will do as her husband says.”

“I would never describe Catherine as dutiful. She is too independent,” Ma said. She took a deep breath and leaned back in the rocker. Then she asked softly, “What you are saying is you expect

me

to be a dutiful wife. You made this decision without consulting me. What if I don’t want to go, Thomas?”

Pa frowned at her. “You are my wife,” he said. “You may stay if you wish, but I will not be here.”

Pa’s voice sounded harsh. Would he really leave us behind? I wondered. He had been away a year, and I’d been afraid that something had happened to him, that he’d gotten sick or had fallen off a mountain. Ma’d never said anything, but I knew she’d worried, too. What would we do if he abandoned us now?

“I have already made inquiries about selling the farm,” Pa said. “Don’t you see, Meggie. I can get enough for the place to buy the building materials and the wagons to transport them.”

“I’ll go, Pa, me and Skiddles,” I said, hugging my cat. I talked in a small voice, because Pa didn’t usually like me to speak up. Children should be seen and not heard, he told me often enough, although I was ten now and thought I had a right to voice my own opinions. I had learned a great deal about Colorado in school and knew it was a wild place, with gunslingers and Indians, outlaws and prospectors. Some of them had found gold just by throwing a hat on the ground and digging where it landed. It sounded much more exciting than Quincy, Illinois, the town closest to our farm. Here I was expected to act like a young lady, to sit and quilt with Ma and Aunt Catherine, and to practice my embroidery. Ma had sent me to a school for girls for a time, a place where I was supposed to learn to have fine manners and cross-stitch a sampler. There hadn’t been enough money for me to continue. I didn’t mind. I wasn’t very good at sewing and had to take out so many of the cross-stitches that I thought my eyes would cross.

But those weren’t the only reasons I spoke up. Ma would never let me go with Pa by myself. She’d have to come with us. We wouldn’t be separated again.

Instead of reprimanding me, Pa smiled. He leaned over and took my mother’s hands. “You see, Meggie, Emmy Blue knows we can get a start in Golden.” His voice softened. “A new start is what we need, Meggie. What will happen if we lose the farm?”

“But the people I love are here,” Ma said. “How can I leave my family, our neighbors? Will I ever sit and quilt with friends again? Moving west is a fine thing for a man. It means freedom and a chance for a better life for you. But it doesn’t mean a thing to me. I’ll be leaving behind everything I care about—home, church, school for Emmy Blue. Who knows if there are schools in Colorado, or churches?”

“If there aren’t, you can start them. Come with me, Meggie. You will do well. You have a stout heart. It will be a better life, I promise.”

“Do I have a choice? There is stubbornness in you as big as a mule.” She looked sad, and I knew she was thinking not only about her family but about the graves in the cemetery, the ones we visited every Sunday. They were marked with a piece of white marble shaped like a tree stump.

Ma didn’t talk much about her babies who had died. She said it wasn’t proper. But I knew she grieved for them, and I did, too. I had loved them, especially my younger sister, whose tombstone read “Agnes Ruth, Our Sweet Baby Girl. Two Years, Three Months, and Seven Days.” Pa would take Ma’s hand as we stood beside the Hatchett graves. Then he’d sigh and put his other hand on my shoulder and say, “I’m glad we have you, Emmy Blue.”

Once the decision was made to go to Colorado, Ma made up her mind to like it. She’d said about dandelions that if we couldn’t do anything about them, we’d just have to enjoy them. That was the way she treated almost everything. If a thing couldn’t be helped, she accepted it. Not that her parents did, though. Grandpa Bluestone told Pa he ought to be horsewhipped for taking Ma out where she could be killed by wild Indians, and Grandma Mouse cried and cried, and said she’d never see Ma or me again.

Grandma Mouse wasn’t her real name. She was called that because she was so small—and because she had a pinched face and beady eyes like a mouse. She was really Emma Bluestone, and I was named for her. Only at the last minute, Ma told me, Pa rebelled at calling me exactly after Grandma Mouse, so he’d written my name in the Bible as

Emily

Bluestone Hatchett.

Perhaps it was a good thing I didn’t have Grandma’s full name, since I was not at all like her. She was tiny, while at ten years of age, I was already a good hand taller, with brown eyes unlike her blue ones. She was fine-boned, while I was gangly and awkward—unladylike, Grandma Mouse said. Ma called me high-spirited. “There is time enough for her to become a lady,” she told Grandma Mouse.

“It wouldn’t hurt for her to begin now. She could start by threading our needles for us. Nothing befits a lady more than fine stitching,” Grandma Mouse said.

One day, then, when Ma’s friends and neighbors, who made up her quilting circle, met at our house, Ma put my best friend, Abigail Stark, and me to work. We were told to sit under the quilt frame while the guests stitched, so that we could thread their needles. We sat there for an hour, the quilt above us, our hands sweaty as we tried to poke the thread through the eyes of the needles. As she licked the end of a thread, Abigail pointed to a woman’s shoe, and I saw that it was untied. The shoe belonged to Miss Browning, a woman we disliked because she said we were disheveled urchins and told on us when we stole apples off her tree. I picked up her laces so gently that the woman did not feel it, at first meaning to tie them for her. But instead, I tied them to the laces of her other shoe. When the women stood up to roll the quilt, Miss Browning tripped and fell against a table, and her elbow landed in a plate of gingerbread Ma had set out. Then she knocked a display of pinecones, resting on the sideboard, to the floor, smashing them.

Grandma Mouse, who had glued the pinecones together, called us disgraceful and insisted we be punished. Miss Browning was unhurt, but she shrieked that the gingerbread had stained the elbow of her white blouse. So Ma, a look of fury on her face, took us both by our arms and dragged us down the hall and into the kitchen, shutting the door.

“Ma—” I began.

Ma put up her hand and shook her head. She clamped her hand over her mouth, because she had begun to laugh. Then she wiped her eyes, because she was laughing so hard, she had begun to cry. “You bad, bad girls,” she said, and began to laugh again. “I have tried to find a way to get rid of those ugly pinecones ever since your grandmother gave them to us. Did you see the look on that pious Miss Browning’s face? Did you notice how many of the other women smiled? Miss Browning is not a favorite among us, and she will never live this down.”