The Psychopath Inside (13 page)

Read The Psychopath Inside Online

Authors: James Fallon

After more years of the up-and-down cycle in my professional performance and wild weight swings, I decided to chart these oscillations on several taped-together pieces of graph paper. What I saw astonished me. After plotting more than thirty years of my weight and professional and creative output, based on publications, grants, patents, paintings, and other artworks, the correlation seemed too perfect. Whenever my weight peaked, several times going to 290 to 300 pounds, so did my professional and creative output. And when I then had lost all the weight, returning to my peak performance college weight of 190 to 210 pounds, my productivity went to zero, often lasting for a year or two.

The more I ate and smoked and partied, and the less I exercised, the better my performance in all professional fields. And I noticed another thing: When I was on the upswing in weight and then peaking, my ability to communicate on a personal level with people close to me seemed to also increase. While gaining pounds and then reaching my pinnacle, weightwise that is, I seemed more connected to people, particularly family members. Somehow these positive traits, intellectual and creative performance and interpersonal connectedness, appeared always connected one to

the other. And when I lost weight, sometimes with the aid of smoking cigarettes, I looked great but was unproductive and lacked any sort of empathy. I became a stud-muffin party boy, perhaps a jerk, on a regular basis. At these times, I especially did not care about how any of my behaviors might hurt other people emotionally or even physically.

I also become more aggressive. Going to baseball games, I sit close to the field and yell at the players (especially A. J. Pierzynski, the catcher for the Rangers), calling them all sorts of names. When other fans complain, I get in their faces: “You wanna fuck with me?” Normally I'm really slow to anger and not physical at all, but when I'm in shape I can tear off the back of the seat. Really, you want to be around me when I'm fat and I've had a couple of drinks. Then I'm a complete sweetheart.

These swings in body and mind, in intellectual and emotional expressiveness, seemed exactly opposite to the way the body and mind are supposed to respond to being in and out of shape. This became a running joke among my friends and me (but not so much to Diane, who was constantly on my case about my health), throughout the 1990s and to this day. I have never figured out why these seventy- to one-hundred-pound swings in weight and behavior occurred, but naturally I suspected abnormally large cycles of activity of serotonin, dopamine, and perhaps the endorphins and testosterone in my limbic system, especially in my temporal lobe and associated limbic/emotional brain where these neurotransmitters, modulators, and hormones were having their greatest convergent impacts. One can guess that alterations in my

serotonin-regulated daily rhythms, including those for sleep, were fueling these wild fluctuations, but this is only speculation. Usually my weight swings happen into their own, but sometimes I'll notice that my ass is knocking into the furniture and decide I need to lose some weight, and I do. I've got quite a strong will when I put it to use.

I had only started to wonder in 2011 about how my changes in connectedness fit into these months- or years-long swings in behavior and body type, when I learned, or rather realized, that there might be something seriously wrong with my ability to have normal interpersonal relationships.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

Empathy can be thought of in several ways. The first way is to contrast empathy with sympathy. Empathy is usually thought of as being able to put yourself in another's shoes, that is, to imagine that what he is experiencing emotionally is something you have also experienced. Sympathy, on the other hand, does not require that one feels or has actually experienced what one might imagine another is experiencing. Sympathy is more of a recognition that something is eating away at someone, and a desire to do something to lessen her pain. Empathy usually refers to one's emotional reactivity to another individual person. An example of sympathy is when someone hears of the plight of earthquake or flood victims and, although not actually having experienced anything like that, still donates time or financial relief to those victims. This is not to say that the compassionate person responding to this need doesn't also empathize with those victims, only that it is not necessary to do so.

Likewise, there are empathetic individuals who sense that they feel the pain of others but do nothing about it to help the other person. The groundbreaking physiological studies of Marco Iacoboni of UCLA offered a mechanism for how brain processes connect people, at least on an intellectual or cognitive-perceptual level.

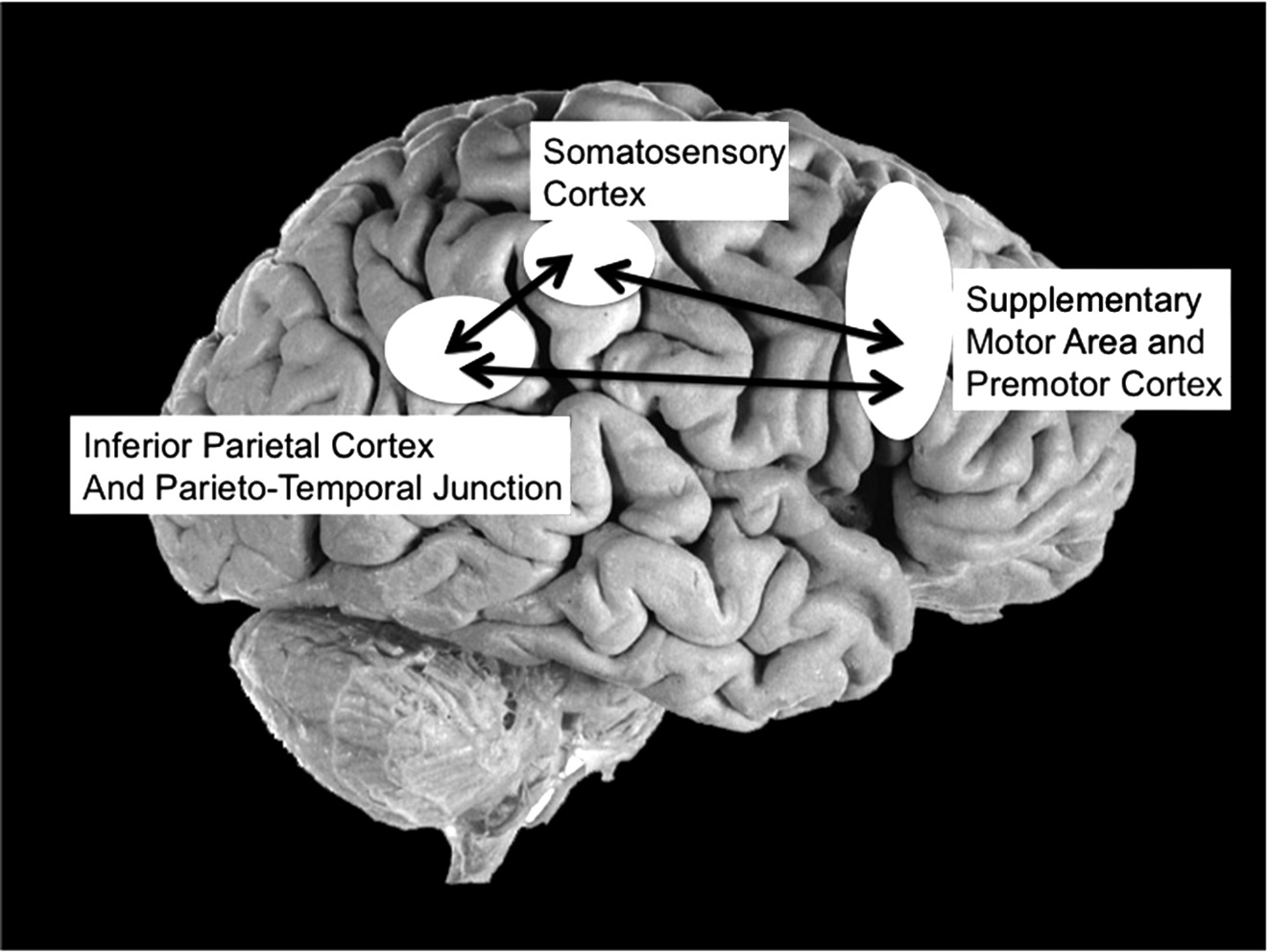

The mirror neuron system is a hypothesized cortical brain circuit based on Iacoboni's finding that in primates there are neurons that respond when a person watches the actions of others and when the person performs the actions himself. The superior ability of primates, especially humans, to watch another do something once, and then be able to do the same thing themselves immediately, is thought to be based on the circuit formed between these neurons in the areas of the frontal lobe and parietal cortex.

This system may help to explain why human children can watch their mother do something, let's say fold a towel, and the child can immediately attempt to fold a towel. The sensory motor system that is used to watch the mother do this is the same group of cells that the brain uses to do the task. More difficult motor tasks may also be mimicked effectively by adults using this mirror neuron system.

The first time I lived in Africa was in 1990 to 1991, when I was in Kenya doing research on growth factors in the primate brain under the auspices of a Senior Research Fulbright Fellowship. My brother Tom, arguably the best athlete among my siblings, journeyed from New York to visit me in Kenya. On one of our safaris, he came with me to visit a village in a remote area near the Ugandan border. The shamba man (gardener) Bernard, who took care

of my Nairobi yard and gardens, had his family out there, and I had provided him and another family with modern roofing (sheet tin) materials, as the rest of the people in his village lived in small round mud homes covered with thatch. Tom and I had also planned to play golf en route, so I had my clubs along for the ride. Many of the people in his village had never seen an actual white person, let alone golf clubs. Tom and I noticed that Bernard's village had a large three-hundred-yard-long field in the back of the homes, so I had Bernard interpret a question to his neighbors: “Would any of you like to learn how to play golf?” Among the hundred or so of his clan amassed there, a few brave souls stepped forward, including the family elder, a gentleman of about eighty years who was dressed in a full suit and a hat with a red Christian cross emblazoned on it.

They first watched as I flubbed a shot about thirty yards, drawing a chuckle from Bernard and a belly laugh from Tom. Then Tom stepped forward and blasted a three wood to the very end of the field, and there were gasps of awe from the gathered clan. Then the elder stepped forward, grabbed one of the clubs (an implement he had never seen, let alone used before), and took a quick and furious swing at the teed-up golf ball. He whiffed it, but no one made a peep. Then within three seconds, as if clearing a field with a scythe, he swung at the ball again, catching it on the sweet spot, and the ball took off about a hundred and fifty yards, with a hint of a slice. Applause erupted from all of us. Then, one by one, every man, woman, and child stepped forward and each one missed with the first swing, and then nailed the ball with the second. Some of the adult men drove the ball more than two hundred yards.

This was an example of the mirror neuron system cranking away with all cylinders firing. The next year when I visited that village, it was like they had created their own two-hole golf association, an effect I never intended to curse them with in the first place.

This mirror neuron system may help explain why humans can quickly pick up a complex task without any practice. Does a similar circuit, one that interacts with the mirror neuron system, process empathy? Although no one knows the details of such a circuit, there are some imaging studies that point to a consistent set of brain areas that are activated in the laboratory setting that illuminates factors thought to be in play in empathy, and the lack of it. Jean Decety of the University of Chicago, Yan Fan at the University of Ottawa, and Knut Schnell at the University of Heidelberg, among others, have all carried out functional brain imaging studies with fMRI to study the elements of empathy. When we see a happy, sad, or angry expression on someone's face, regions responsible for those emotions light up in our brains, too. Taking the basic mirror neuron system, a cognitive circuit, and adding in areas that are connected to the mirror system but that process emotion, we can envisage a broader circuit underlying empathy. These additional areas include the insula, an area of cortex “insulated” from view by the outer folds of the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices that all connect to it, plus the emotion-mediating anterior-medial temporal lobe and amygdala, not seen in a surface view of the side of the brain.

Those regions connect with the orbital and inferior frontal cortices. These three areas are represented in figure 7A that follows. These then connect with and control the hedonism, pleasure, stress, and pain areas deep in the brain, which are bathed in serotonin, dopamine, testosterone, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), and endorphin receptors, as well as vasopressin and oxytocin systems.

FIGURE 7A:

Mirror neuron system.

These hormone and neurotransmitter systems, as it turns out, play a significant role in empathy. Simon Baron-Cohen of the Universities of Reading and Cambridge, Paul Zak of Claremont Graduate University, and Sarina Rodrigues at the University of California, Berkeley, among others, have demonstrated

the importance of the genetic alleles that process these empathy-related neurochemicals, which affect a range of empathy-related sensations, from fear, rejection, pain of separation, envy, jealousy, selfishness, and schadenfreude, to the positive end of this spectrum where we find sympathy, pity, compassion, familial and tribal connectivity, generosity, trust, altruism (if there is such a thing), romantic love, and, perhaps, love of country, humanity, and God.

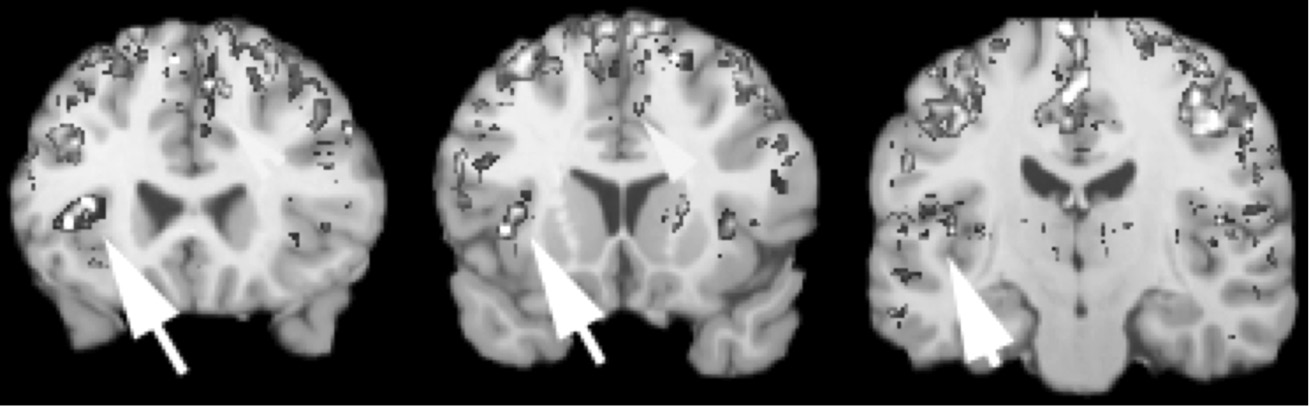

For a comparison of brain activity in the areas that process emotional empathy, refer to figure 7B below. In these three cross sections of the PET scans through my brain, the region of my insula with an abnormal mix of very low and very high activity is identified by the tips of the white arrows. You can't tell in this black-and-white reproduction, but that area is shaded to indicate decreased activity. Another area involved in empathy, the anterior cingulate, also has lower activity in my brain. Meanwhile, the areas of cortex on top of the brain are significantly

higher

in activity in me compared to other people. This may be associated with cold cognition.

FIGURE 7B:

My PET scan.

Given the myriad brain areas and genes involved in what we simply call empathy, perhaps it is not too surprising that the term and its meaning have proliferated into so many different descriptors and their related concepts. We usually associate lack of empathy with psychopathy, and rightly so, because although most psychopaths are not violent, they often treat individuals in a callous, almost numb wayâthey just don't care. But many express caring for something, and often someone. Even psychopathic murderers will express their love for their parents and siblings, even if those same people were the ones who initially triggered the psychopathic tendencies through abuse and abandonment early on in the psychopath's life. Think of the Buffalo Bill character from

The Silence of the Lambs

, who butchered innocent women without a second thought but became noticeably anxious when his poodle was in danger.

But those same psychopaths may hate the rest of society and be out to exact revenge, both violently and nonviolently.