The Prose Edda (4 page)

Authors: Snorri Sturluson

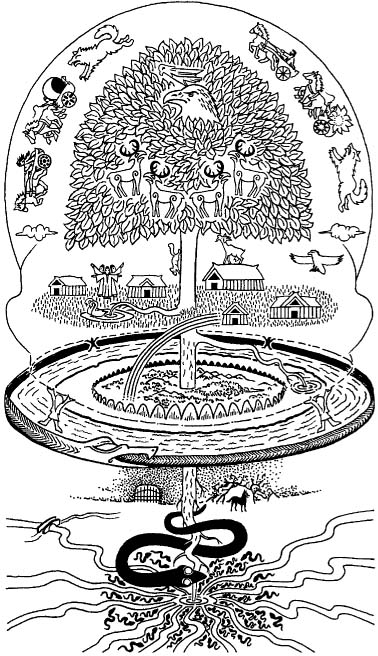

Rising into the heavens, the World Tree Yggdrasil was a living entity, whose branches spread over the lands. This

axis mundi

or cosmic pillar at the centre of the world is described as a giant ash, binding together the disparate parts of the universe and serving as a symbol for a dynamic cosmos. Above the branches and foliage of the tree are the heavens, formed from the skull of the primordial giant Ymir, and held in place by four dwarves. In the heavens, Sun and Moon are pulled by chariots and chased by wolves. The giant Hraesvelg, in the shape of an eagle, beats his wings, blowing the winds. In response to the question, âHow should one refer to the sky?', a passage in the

Edda

tells us: âBy calling it Ymir's head and hence the giant's skull, the burden or heavy load on the dwarves, the helmet of the dwarves West, East, South and North, the land of the sun, moon, heavenly bodies, constellations and winds, or the helmet or house of the air, of the earth and of the sun'

(p. 112)

. Below the tree's branches lies Asgard, the home of the gods and the prophetic women called norns. From Asgard, the Rainbow Bridge, Bifrost, leads down to Midgard (Middle Earth), the home of men. A wall encloses Midgard, separating it from the outer region, Utgard, the land of the giants. Beyond Utgard is the outer sea, in which the encircling Midgard Serpent lies, biting its tail. Below is the underworld, containing monsters, serpents and a great hound, as well as the realm of the dead and seething rivers. For a fuller discussion of the World Tree and the Norse cosmos, see

Appendix 1.

be dwarves. Other indications of the importance of elves in the supernatural world of Old Scandinavia include place names connected with their veneration. Many folk tales and medieval sagas also speak of elves. For example,

Kormak's Saga

, a rich source of folk religion and sorcery in medieval Iceland, provides insight into the role of elves. After a duel, the wounds of Kormak's opponent are slow in healing, and he seeks the advice of a sorceress, who says: âNot far from here is a small hill in which elves live. Get the bull that was slaughtered by Kormak. Redden the surface of knoll with its blood and make a feast for the elves from the meat. Then you will get better.'

2

Among the monsters who most threaten the gods are the children of Loki. One is the wolf Fenrir, who in the final battle swallows the sun, another is the gigantic Midgard Serpent, who lies in the outer sea, encircling all lands, and the third is Hel, who oversees the realm of the dead. The gods are so fearful of Fenrir that they decide to bind the wolf while still a cub. Only mighty Tyr, a god of war and battle, calms the young wolf long enough to allow the other gods to bind it with a magic fetter, although Tyr loses his hand in the process.

Edda

in Iceland and Beyond

Written on the far northern edge of the medieval world, the

Edda

is an extraordinary document for its invaluable insights into the language and techniques of Viking Age skalds, and this was one of the principal reasons that Icelanders took care to preserve the

Edda

by repeatedly copying it. Iceland was an unusually literate society in the Middle Ages, and copying manuscripts of all kinds was a pastime that remained popular among the Icelanders down to the beginning of the twentieth century. In the medieval period, Icelandic manuscripts were made of calf skin (vellum) and were expensive to produce. In early modern times, Icelanders began to import inexpensively manufactured blank paper books, and one piece of evidence of the

Edda

's continuing popularity is that over 150 paper copies of the

Edda

survive, many from the nineteenth century.

The

Edda

's wealth of information about Old Norse mythology

was another reason for the Icelanders' continued interest in the work. It was also the major reason why, starting in early modern times, the

Edda

gained fame outside Iceland. The

Edda

's entrance into the wider world of western culture is itself a story. In the sixteenth century, Denmark was an aggressive power in Northern Europe, seeking primacy in Scandinavia and, in common with the rulers of states elsewhere in Europe, the Danish kings strove to enhance their ambitious political agenda by documenting the antiquity and legitimacy of their history. For this purpose, the Danish state adopted as its own the mythic and heroic past of all Scandinavia.

Iceland became a possession of the Danish king in the late fourteenth century, and by the sixteenth century the Danes had discovered that Iceland's medieval manuscripts were a treasure trove, containing information about Scandinavia's past found nowhere else. Icelanders sent manuscripts to the king as gifts, and these and many others found their way into the archives and royal libraries in Copenhagen. The Danish king went so far as to command the Icelanders not to sell their manuscripts outside the kingdom. With the royal government as patron, Icelandic students and scholars were invited to Copenhagen to study and work on the manuscripts. Among the most important of these scholars was the humanist Arngrimur Jonsson (1568â1648), whose influential book

Brevis Commentarius de Islandia

(

Short Commentary About Iceland

), published in Copenhagen in 1593, brought Iceland's medieval writings, including the Edda, to the attention of scholars outside Denmark. Jonsson's popular work fuelled a growing awareness of the

Edda

beyond Scandinavia that eventually led to a series of translations of the

Edda

into modern languages. The first translation of

Gylfaginning

into English appeared in London in 1770, as part of a book by Bishop Percy entitled

Northern Antiquities

. This book soon gained a readership, and in 1809 Sir Walter Scott reprinted it in Edinburgh with his own additions. By the nineteenth century, readers of most major European languages were able to learn about the gods, giants, dwarves, elves and other creatures who populated the cosmos of Old Scandinavian belief and imagination. For allowing us to glimpse this complex universe,

we owe a debt of gratitude to Snorri Sturluson and the other Icelanders who contributed to writing and preserving the

Edda

.

1.

Snorre Sturlusons Edda: Uppsala-Handskriften DG 11

, vol. II, transcribed by Anders Grape, Gotfried Kallstenius and Olof Thorell (Uppsala, 1977), p. 1.

2.

Kormáks Saga

in

Vatnsdæ la Saga

, ed. Einar Ãl. Sveinsson.

Ãslenzk fornrit

VIII (Reykjavik, 1939), chapter 22. For an English translation of

Kormak's Saga

, see

Sagas of Warrior-Poets

, ed. Diana Whaley (London and New York, 2002).

STUDIES

Ciklamini, Marlene,

Snorri Sturluson

(Boston, 1978).

Clunies Ross, Margaret,

Skáldskaparmál

(Odense, 1987).

Davidson, H. R. Ellis,

Gods and Myths of Northern Europe

(London and New York, 1981).

De Vries, Jan,

The Problem of Loki

(Helsinki, 1933).

Dubois, Thomas A.,

Nordic Religions in the Viking Ages

(Philadelphia, 1999).

Dumézil, Georges,

Gods of the Ancient Northmen

(Berkeley, 1973).

Edda: A Collection of Essays

, ed. R. Glendinning and H. Bessason (Manitoba, 1983).

Faulkes, Anthony, âDescent from the Gods',

Mediaeval Scandinavia

11g (1978â9), pp.

92â125

.

â, âThe Sources of Skáldskaparmál', in

Snorri Sturluson

, ed.

A. Wolf,

Script Oralia

51(Tübingen, 1993), pp.

59â76

.

Gade, Kari E.,

The Structure of Old Norse dróttkvætt Poetry

(Ithaca, NY, 1995).

Harris, Joseph, âThe Masterbuilder Tale in Snorri's Edda and Two Sagas',

Arkiv för Nordisk Filologi

91 (1976), pp.

66â101

.

Lindow, John,

Norse Mythology

(Oxford, 2002).

McTurk, Rory, âFooling Gylfi',

AlvÃssmál

3 (1994), pp.

3â18

.

Nordal, Gudrun,

Tools of Literacy

(Toronto, 2001).

Poole, Russell,

Viking Poems on War and Peace

(Toronto, 1991).

Quinn, Judy, âEddu list',

AlvÃssmál

4 (1995), pp.

69â92

.

See, Klaus von, âSnorri Sturluson and the Creation of a Norse Cultural Ideology',

Saga-Book

25, 4 (2001), pp. 367â93.

Snorrastefna

, ed. Ãlfar Bragason (Reykjavik, 1992).

Specvlvm Norroenvm

, ed. U. Dronke

et al

. (Odense, 1981).

Turville-Petre, E. O. G.,

Myth and Religion of the North

(London, 1964).

Uspenskij, Fjodor, âTowards Further Interpretation of the Primordial Cow

Auðhumla'

,

Scripta Islandica

51 (2000), pp.

119â32

.

The Poetic Edda

, tr. C. Larrington (Oxford, 1996).

The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki

, tr. J. L. Byock (London and New York, 1998).

The Saga of the Volsungs

, tr. J. L. Byock (London and New York, 1999).

The Saga of the Ynglings

, in

Heimskringla

, tr. L. M. Hollander (Austin, Tex., 1999), pp. 6â50.

Saxo Grammaticus,

The History of the Danes, IâIX

, ed. H. E. Davidson, tr. P. Fisher (Cambridge, 1996).

Seven Viking Romances

, tr. H. Pálsson and P. Edwards (London and New York, 1985).

Tacitus, Publius Cornelius,

The Agricola and The Germania

, tr. H. Mattingly, revised S. A. Handford (London and New York, 1970).

Byock, Jesse L.,

Viking Age Iceland

(London and New York, 2001).

Foote, Peter G., and David M. Wilson,

The Viking Achievement

(London, 1970).

Haywood, John,

The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings

(London and New York, 1995).

Kristjánsson, Jónas,

Eddas and Sagas

(Reykjavik, 1997).

Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia

, ed. P. Pulsiano

et al

. (New York, 1993).

Orchard, Andy,

Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend

(London, 2002).

Simek, Rudolf,

Dictionary of Northern Mythology

(Cambridge, 1993).

Faulkes, Anthony,

Edda by Snorri Sturluson: Prologue and Gylfaginning

(Oxford, 1982) and

Edda by Snorri Sturluson: Skáldskaparmál

, 2 vols. (London, 1998).

Helgason, Jon and Anne Holtsmark,

Edda: Prosafortellingene av Gylfaginning og Skáldskaparmál

(Copenhagen, 1968).

Jónsson, Finnur,

Edda Snorra Sturlusonar

(Copenhagen, 1931).

Neckel, Gustav,

Edda: Die Lieder des Codex Regius

,

Vol. I

,

Text

(Heidelberg, 1927).

All modern editions of the

Prose Edda

rely on the largely intact vellum

Codex Regius

manuscript (Gks 2367 quarto) from the first half of the fourteenth century. This manuscript, however, has gaps, and three other key manuscripts provide the majority of the missing passages and variant readings. They are the vellum

Codex Upsaliensis

from the early fourteenth century, the mid-fourteenth-century vellum

Codex Wormianus

and a paper book,

Codex Trajectinus

, a copy from around 1600 of an earlier vellum manuscript now lost. This translation from the Old Icelandic draws its text from the modern editions of the

Edda

cited in the Further Reading.

The

Prose Edda

, all or parts of it, was translated into English three times during the last century, by Arthur Brodeur (New York, 1916), Jean Young (Cambridge, 1954) and Anthony Faulkes (London, 1987). Only the Faulkes' translation includes

Hattatal

. The chapter and section headings in this translation are my own, and I believe that they will facilitate the reading of the

Edda

and its use as a source. Also, where

Gylfaginning

incorporates stanzas from eddic poems into its prose, the names of the poems and the corresponding stanzas are given.

This book contains three appendices designed for those readers who want more information on the World Tree and cosmos, the devices of Old Norse verse, and which eddic poems were used as sources for

Gylfaginning

. At the end of the book there is also an extensive Glossary of Names. I compiled this index to provide the reader with a tool for locating the characters (both supernatural and human), groups, places, animals and objects that appear in the text. Also at the end of the

volume the reader will find genealogies and notes. In the Glossary, Notes and Further Reading I include Old Icelandic spellings; elsewhere accents are dropped and the spelling of proper names and special terms are anglicized, usually by omitting the Old Norse endings and replacing non-English letters with their closest equivalents. I do not strive for complete consistency, especially when a name is familiar to English speakers in another form; thus, I use

Valhalla

rather than

Valhöll

. My goal throughout is to produce an accurate translation in a clear modern idiom that best reproduces the nature of the original prose.