The Prose Edda (20 page)

Authors: Snorri Sturluson

Reading the

Edda

with an awareness of the techniques employed by skalds or poets greatly adds to the reader's understanding and enjoyment of this text. The most frequent device used in these word games is the naming of people and things by metaphors called kennings, a word which comes from the verb

at kenna

, which has several meanings, including âto name and to call'. The other common device is the use of synonyms called

heiti

, a term which means âname' and derives from the verb

at heita

, âto name'.

Heiti

were mostly nouns used to replace more common nouns, but

heiti

could also be proper nouns. For instance, skalds referred to Odin as Ygg, a

heiti

meaning âterrible one'. When referring to Odin's son, Thor, a skald might use the

heiti

Ygg to build the kenning Ygg's child. Such a kenning increased a skald's word choice by paralleling other kennings, which may depend on kinship bonds, but do not employ

heiti

, as, for example: Odin's son, Sif's husband, Modi's

father, friend of men, lord of he-goats, relation to Odin, enemy of the wolf, slayer of the serpent, killer of giants and griefmaker of giantesses. All of these allusions are explained in tales gathered in the

Edda

.

Kennings at their simplest are phrases composed of a base noun qualified by a possessive noun. In the kenning âicicle of blood', meaning sword, âicicle' is the base word and âof blood' is the qualifier in the possessive. Other examples are âhorse of the sea' for ship, and âmoons of the forehead' for eyes. The raven became âswan of blood' because it ate the battlefield dead. Kennings have a logic and require a knowledge of Norse society and mythology to construct them. For example, a chieftain is referred to in the

Edda

as âbreaker' or âdistresser of rings', reflecting the common practice whereby leaders rewarded followers by breaking off pieces from their gold or silver arm rings and giving them as gifts.

Sometimes several kennings were strung together into one complex kenning. For example, a leader could be called âspurner of the bonfire of the sea'. The spurning refers to the generosity of a leader, whereas âbonfire of the sea' is a kenning for gold, because there were stories about Ãgin, a lord of the sea, whose home fires burned red, like gold beneath the sea. The audience for this poetry expected a good skald not only to replace a commonplace word like gold with a kenning, but also to be able to construct in a creative manner several kennings for the same commonplace word. Another kenning for gold was âOtter's ransom', an allusion to the gold that Odin had to pay as compensation to the giant Hreidmar for killing his son Otter, who had changed his shape to that of the animal (see

Skaldskaparmal

7). Kennings appealed to skald and audience, because they awakened a shared understanding of Norse history and lore.

In stanza 3 of his poem

Hattatal

, Snorri offers several examples of kennings, concentrating on those meaning âearth' or âland':

The glorious

spurner of the bonfire of the sea

(

giver of gold

)

defends the

woman friend of the adversary of the wolf

(

Earth or land

).

The ship runs up in front of the steep

brows of the lady of the friend of Mimir

(

cliffs

).

The mighty lord has the power to retain

the mother of the destroyer of the serpent

(

Earth

).

Distresser of rings

, may you enjoy (

giver of Rings

)

the mother of the foe of the giantess

until old age (

Earth

).

1

The following stanza from

Gylfaginning

(on p.

10

) provides a rich example of a kenning that assumes the audience shared knowledge of specific historical events along with mythology.

On their backs they let shine

hall shingles of Svafnir,

when bombarded with stones,

those resourceful men.

This stanza is employed in the

Edda

for several purposes. First, it reminds the audience that Svafnir is another name for Odin. Second, the kenning for âshield', âhall shingles of Svafnir', turns on the understanding that Valhalla was roofed with shields in the manner of wooden shingles. The stanza, however, is older than the

Edda

. Just how old we do not know but it comes from a skaldic poem commemorating the famous victory about the year 870 by Norway's King Harald Fairhair. It is a mocking reference to Harald's enemies, who are resourceful in covering or roofing their backs with their shields as they flee.

Heiti

, or synonyms, allowed skalds to replace a common word, such as âhorse', with the more poetic, âsteed'. Most

heiti

(the word is both singular and plural) are more obscure than this example and require a familiarity with Scandinavian myth and legend that the

Edda

provides. Largely because of

heiti

, Norse poetry has its own vocabulary or lexicon, and mastering the art of poetic composition means learning new meanings and names. In

Gylfaginning

High explains that Odin is known by many names:

All-Father in our language, but in Asgard the Old, he has twelve names: one is All-Father, a second is Herran or Herjan, a third is Nikar or Hnikar, a fourth is Nikuz or Hnikud, a fifth is Fjolnir, a sixth Oski, a seventh Omi, an eighth Biflidi or Biflindi, a ninth Svidar, a tenth Svidrir, an eleventh Vidrir and a twelfth Jalg or Jalk. (p.

11

)

Heiti

fall into several groups. One is ancient words used only in poetry. A good example of this group is the word

gumi

, meaning âman'. Although

gumi

is found in prose compound words, such as the word for bridegroom (

brudgumi

), as a single word

gumi

is never found outside poetry. Another example of

heiti

from this group is the word

drasill

, meaning horse, as in Yggdrasil (

Yggdrasill

), meaning Odin's horse. Many

heiti

for the gods fall into this group. For example, Hnikar and Fjolnir in the above list of names for Odin are found only in the poetry. Hence they are listed in the

Edda

for aspiring skalds to learn. Another important group consists of words well known in prose but with different meanings in poetry. An example is the word (

brúðr

) bride. In prose it refers to a woman who is about to marry, but in poetic diction

brúðr

had the broader meaning of âwoman'.

1.

My thanks to Russell Poole for translating this stanza.

Gylfaginning

The mythic stories in

Gylfaginning

rely to a large degree on eddic poetry. Some of these poems are now lost. For example,

Gylfaginning

, chapter 27, mentions

Heimdall's Chant

(

Heimdalargaldr

), but this eddic poem no longer exists. Many eddic poems, however, survive in the

Poetic Edda

. Below is a list of the mythological eddic poems cited in

Gylfaginning

which are found in the

Poetic Edda.

The Lay of Fafnir

(

Fáfnismál

)

The Lay of Grimnir

(

GrÃmnismál

)

The Lay of Hyndla

(

Hyndluljóð

)

The Lay of Skirnir

(

SkÃrnismál

)

The Lay of Vafthrudnir

(

Vafprúðnismál

)

Loki's Flyting

(

Lokasenna

)

The Sayings of the High One

(

Hávamál

)

The Shorter Sibyl's Prophecy

(

Völuspá in skamma

)

The Sibyl's Prophecy

(

Völuspá

)

At times, stanzas found in the

Poetic Edda

vary from their counterparts in the

Prose Edda

. This suggests that the author of the

Edda

may have known the eddic poems orally or in a different written form. In some instances the differences of wording between lines found in the

Prose Edda

and the

Poetic Edda

can be significant, as is often the case with

The Sibyl's Prophecy

. In the

Poetic Edda

the third stanza of

The Sibyl's Prophecy

opens with the line: âEarly of ages, when Ymir dwelled'. Yet the stanza in the

Prose Edda

mentions only a void and not the giant Ymir: âEarly of ages, when nothing was'. This difference in wording changes the picture of the creation. So also the

Edda

and the

Poetic Edda

sometimes employ different

terms. The

Edda

calls the final battle at the end of the world by the singular word Ragnarøkr, meaning âTwilight of the Gods' or âDarkness of the Gods'. With the exception of

Loki's

Flyting, eddic poems employ a different word, Ragnarök, meaning âEnd of the Gods' or âDoom of the Gods'.

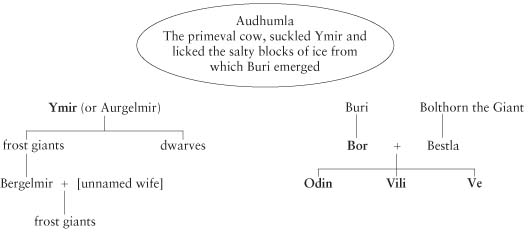

Ymir and the Sons of Bor

Dwarves and giants developed from the body of the primordial giant, Ymir (also called Aurgelmir by the frost giants). The dwarves grew in Ymir's flesh. The frost giants were created from Ymir's sweat âunder his left arm' while one of his legs âgot a son with the other'. These first generations of giants drowned in Ymir's blood when the sons of Bor killed him. The only survivors were Bergelmir and his wife. From them came a second family of frost giants.

1

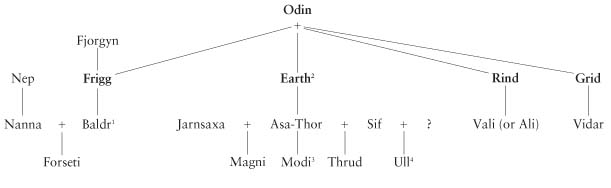

Frigg is not explicitly named the mother of Baldr, but in the

Poetic Edda

this motherâson relationship is clear. Vidar and Hermod are also sons of Odin, but

Gylfaginning

does not name or allude to their mothers.

2

Earth is said to be both a wife and daughter of Odin, as well as the mother of Thor.

3

Modi's mother is not given, but Modi and Magni are often mentioned together.

4

Ull is said to be Thor's stepson.

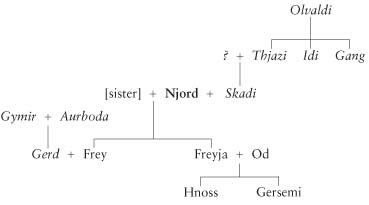

Both Njord and his son Frey marry daughters of giants. (

Italics

denote giants.)