The Perfect Ghost (22 page)

If Malcolm had invited you for a drink, you’d have accepted, no doubt about it. How bitterly I regretted my decision to refuse. Which foster mother had dictated the terms of my hasty retreat? The one who foretold I’d never be pretty enough to date, much less wed a man?

On ran my thoughts till they came up against Hamlet’s dilemma: Was the Ghost a heavenly messenger sent to tell the truth, or a deceitful vision from hell? How do you interpret the evidence of your own eyes? Fact: Brooklyn Pierce lay drunk on the floor of the beach shack. Everything else was speculation. Except the manuscript, the new Ben Justice screenplay. Was that the secret of the tape, Teddy? Was that the revelation Pierce wanted to retract?

How far, how far, had I run? Should I turn away from the shore, strike across the dunes, up and over the gentle hills? Spiders crawled through my veins, numbing my legs. Where was the barn, the parking lot, the car?

“What in hell do you think you’re doing?”

The voice came from behind me, but at first I didn’t know if it was inside my head or outside it, real or imaginary, separate from or part of my terror.

“I said you could interview me, not spy on me. Where the hell have you been? What the hell do you think you’re doing?”

With no breath I couldn’t form any words, let alone the right ones.

Garrett Malcolm looked as full of wrath as any angry stepfather. I wanted to warn him—that Brooklyn Pierce was lying on the floor, drunk and vulnerable, that a man named Glenn McKenna had a nasty habit of photographing Brooklyn’s refuge—but my tongue was a dead, twisted stump that had withered in my mouth.

“What are you holding? What have you got there?”

Not till he asked did I realize I had tucked the new Ben Justice manuscript under my arm, carried it away from the shack like a prize. In an instant, I felt my skin go clammy and cold. I would be accused of stealing. I hadn’t stolen it, not really, not intentionally. I’d only wanted to keep it safe. Really I hadn’t thought. I didn’t know. I couldn’t speak.

“Give it to me.”

My arms were pegs glued to the sides of a wooden statue. I tried to move them, to give the towering, raging man what he wanted, whatever he wanted. He grabbed at me, at the manuscript, and I heard it, felt it rip, saw the pages spew onto the ground, scatter with the wind.

He swore at me. He stormed. Words were at the center of the cyclone, dimly heard and slowly perceived, heard as if from a great distance, and they said I was incompetent and a fool. They said the project was over, cancelled, that this was the end of the line.

CHAPTER

thirty-two

I don’t know how I found the car or fumbled open the door or drove to the rented house. My face, unrecognizable in the rearview mirror, was pink and red and blotchy. I couldn’t stop staring at my wrist, which was marked by a livid bracelet of white and a stinging scratch, fierce keepsakes of the struggle for the manuscript, shameful reminders of Malcolm’s steel grip and my complete inability to defuse the situation, to defend myself, to state the facts. So totally focused was I on my wrist that I should have driven off an embankment or into a ditch. Even after the bracelet faded, I felt it like a burn, like a ring of flame, as though the outline of his thumb and fingers were tattooed on my skin. I could feel it, and I couldn’t feel anything else. I couldn’t hear. I saw only the road immediately ahead of me, as though I wore blinders, and the road was a path to ruin.

I floated out of the car, carefully locked the doors, outside of my own body, watching myself, and then I was inside the house, tossing clothes in the direction of my duffel. Gathering scattered papers, sorting them into haphazard piles, disconnecting my computer. My mind seemed to shift—in control, then out of control. I could imagine myself calmly finishing the book, turning it in to Jonathan, saying nothing about any problem, Malcolm saying nothing. I could see myself naked, surrounded by whispering strangers who muttered and stared and said that once I had been half of T. E. Blakemore, once I had owned a name, even if only half a name, but then I had done something so vile, so reprehensible, that no one hired me again. I saw myself as a bag lady, limping over a smelly sewer near the bus station, muttering to myself. As a suicide, hanging from a tree.

My cell phone rang and I started, then froze. I thought,

I should I answer it.

I thought,

Who would call me?

Teddy, you called me. You were the only one. How I missed you. I could have gone home to you, confessed, and been forgiven. I could have crushed you in my arms and you would have Teddy-bear-hugged me in return and it would have been all right. You deserted me. You left when I still needed you.

The phone rang again and panic rose in my chest, surging, cresting and subsiding, breaking off pieces of me with its rise and fall. I felt as insubstantial as sea foam, battered and crushed. I sank to the floor and yanked the ringing phone from my pocket, and for a moment I thought it would have to be you.

“Hey.” The voice was Jonathan’s. I checked the screen. The number was Henniman’s. I tried to speak, but my voice was lost in my throat.

“Em? Hey, it’s Jonathan. We did a deal with the Literary Book Club. Marcy thought you might like to hear it from me. Hey, are you there?”

“Hi. Yes.” I sounded like a mouse, a strangled mouse.

“It’s not a great deal, okay? Not as much as the last one, but you know what’s going on in the industry. Marcy’s got the figures.”

“Yes.”

“So, you’re good with the manuscript on the twenty-fifth? You can send a disc. That’s better than paper. We’re going to run with T. E. Blakemore on this one. Do you have a definite title yet?”

Tears started down my face. I whispered something about calling him back and punched the button to end the call. I pressed both hands to my eyes and thought, this can’t be happening. I would have to call Marcy, tell her it was over. I would have to—

There was a sharp rap at the door and I realized I hadn’t locked it just as the name “McKenna” solidified into a scary, threatening shape in my mind. Somehow he’d been watching, somehow he knew. He’d been in a boat with a camera trained on the beach shack. I anticipated the smelly gossipmonger charging into the room. He knew everything. He had photos of my wild rush down the staircase, my theft of the screenplay, video he’d splash across the Web site. Then the doorknob turned and Garrett Malcolm called my name.

And he was across the room before I could say a word and his long arms hauled me to my feet and I thought for a minute he was going to kill me and then I clung to him the way I used to cling to you, Teddy. And he killed me, Teddy. He killed me and gave me a new birth and I clung to him and he smothered me and we stumbled toward the door and closed it and locked it and pulled the shades.

We did all that, but our lips never parted. We never stopped kissing each other. We never stopped kissing as we stripped off layers of clothing, mine damp and sandy where I’d fallen to the ground. We never stopped kissing until we’d climbed the stairs and used the bed for what it was made for. He kept saying how sorry he was that he’d made me cry, that I was too young, too sweet, too innocent.

There must have been awkward intervals, even brutal ones. I’m usually shy about exposing my breasts, so far removed from centerfold proportions, but I don’t remember a moment of hesitation.

Teddy, it was a hunger, a need. I could say I didn’t know what came over me, what I was doing, but I did, and it was like a wave, a deluge, a tsunami after a roiling earthquake. It was a spreading fog, a haze, and its color was red, veering into violet. It was the ozone smell of a thunderstorm before lightning strikes, a mouthful of red wine. My hands grazed the electric hair on his chest and came alive, each separate finger thrilled by its discoveries. Rough sheets rubbed the satin of salty skin, and his eyes, oh, his eyes were the melted indigo of ice crocuses. And I was a dry spring flooded and refreshed, bubbling with life, spilling over with icy water and boiling water and all the currents of an unfathomable sea.

PART

two

Whoever turns biographer commits himself to lies, to concealment, to hypocrisy, to embellishments, and even to dissembling his own lack of understanding. Biographical truth is not to be had, and even if one had it, one could not use it.

Sigmund Freud,

in a letter to a friend

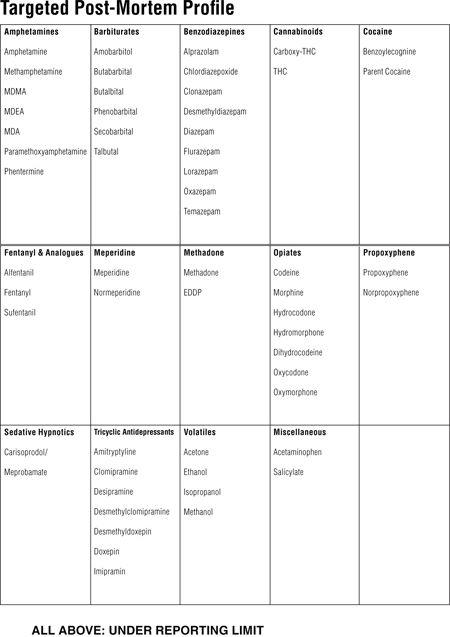

UMass Memorial Labs

UMass Medical Center, Inc.

365 Plantation Street

Worcester, MA 01605

DRUG SCREEN RESULT: TRACE OF HYDROXYZINE

CANNABINOID SCREEN: NEGATIVE

BLOOD ALCOHOL: .02

SPECIMEN IDENTIFICATION: THEODORE BLAKE

DATE SPECIMEN RECEIVED: 3/23

DATE TEST PERFORMED: 4/25

SPECIMEN SUBMITTED BY: L. Hirshoff, M.D., pathologist

TECHNOLOGIST: R. L. MacKenzie

CHAPTER

thirty-three

Forgive me, Teddy, you’ve been largely absent from my thoughts for weeks, but I’ve been such a busy girl and I’m working so hard—honestly, I am—sprinting toward the finish line. Jonathan extended the deadline once Garrett put his foot down, which was so kind of him, of both of them, and I have been a trifle wicked, taking advantage of unseasonably warm weather, lying on the beach, soaking in the early spring sunshine when I should have been dutifully pecking at the keyboard.

God, Teddy, doesn’t the previous graph read like a sweet little Catholic girl talking to her priest? “Father, forgive me, it has been two weeks since my last confession, and during that time I have…” Enough of that. Let me state instead that the days have been incredibly sunny and the sky a cloudless robin’s-egg blue. It would be utterly perfect if you were here.

But then if you were here, I wouldn’t be.

Weighed in the balance, I know my exquisite happiness doesn’t compensate for your death. I know you didn’t willingly die for me. Who would sacrifice their only, their unique life for someone else’s? I’ve read tales of loving parents tenderly laying down their lives for their children, fathers for daughters, mothers for sons, but I never met such parents.

My estate has changed: I’ve moved up in the world, ascended to the Big House. I have to pinch myself, to make sure I’m fully conscious, especially when I wake in my bedroom, my head cushioned by the coolness of an embroidered pillowcase, and lie quite still, looking out at a vast sweep of ocean instead of a cracked plaster wall.

It’s not “my” bedroom; I’m aware of that. It’s formally designated a “guest room,” and I often speculate, late at night, concerning the identity of previous tenants. Was this once Claire Gregory’s boudoir? It shares the same dramatic ocean view as the small office with the mechanical shades, although in some ways this view, elevated as it is on the second floor, is superior. Furnished for visiting royalty in pink and gold, the room has a huge brass bedstead and carpeting so thick it tickles my feet. I spend an immense amount of time here. There’s an elegant writing desk, but I prefer writing in bed, nested in crisp percale and soft down, pounding diligently at my laptop, inhaling Garrett’s piney scent.

While it lacks a connecting door to Garrett’s bedroom, it opens off the same short corridor, so the two rooms form a kind of suite, each with its own bath. Jonathan is terribly impressed by my “access” to the subject. What would he say if he knew?

Teddy, I have qualms, a jittery feeling in my stomach that registers somewhere in between too much champagne and incipient nausea. All my dithering about whether knowing the subject would influence my writing, and now this. Occasionally I convince myself that it’s helping me paint a fuller, truer portrait of the man, but I know I’m justifying behavior I would label unconscionable in anyone else. What can I say? It happened, and I’m not sorry it happened. It’s transformational, this closeness, almost like he’s my working partner now, my writing partner, like we’re truly in this together. Oh, it would have been better if he’d waited, better if the book were already done and published. So we’re keeping it quiet, as quiet and secret as mice. I’m completely invisible here, but then I’m used to being invisible.