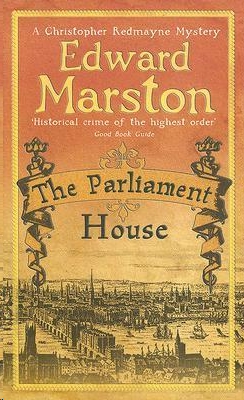

The Parliament House

Read The Parliament House Online

Authors: Edward Marston

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Historical

The Parliament House

Edward Marston

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by

Allison & Busby Limited

13 Charlotte Mews

London WIT 4EJ

www.allisonandbusby.com

Copyright © 2006 by EDWARD MARSTON

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not,

by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or

otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior

written consent in any form of binding or cover other than

that in which it is published and without a similar condition

being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser.

A catalogue record for this book is available from

the British Library

.

10 98765432 1

ISBN 0 7490 8285 2

Printed and bound in Wales by

Creative Print and Design, Ebbw Vale

EDWARD MARSTON was born and brought up in South Wales. A full-time writer for over thirty years, he has worked in radio, film, television and the theatre, and is a former chairman of the Crime Writers' Association. Prolific and highly successful, he is equally at home writing children's books or literary criticism, plays or biographies, and the settings for his crime novels range from the world of professional golf to the compilation of the Domesday Survey. The Parliament House is the fifth book in the series featuring architect Christopher Redmayne and Puritan Constable Jonathan Bale, set in Restoration London after the Great Fire of 1666.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

The shot came out of nowhere. He had removed his helmet to wipe away the perspiration dribbling down his face when he heard the sound of gunfire. The musket ball missed his right eye and ploughed a searing furrow along his unprotected temple. He felt as if someone had just used a hot chisel to gouge out skin and bone from the side of his head. Agony blended with fear. Blood mingled with sweat. Dropping his helmet, he tried to maintain his balance but his legs began to buckle under him. His mind was racing, his vision blurred. Sliced wide open, his right ear seemed to have trebled in size and turned into solid lead, weighing him down so hard that he keeled over and hit the ground with a thud. It was only then that he was able to let out a long, loud cry of despair.

It had all happened many years before, but Bernard Everett had never forgotten that fateful moment in September 1651, when he thought, mistakenly, that the battle was all over. He still carried the livid scar along the side of his head. Other men would have grown their hair over it or worn a periwig to hide the wound completely, but Everett bore it as a mark of honour. The ugly slit and the shattered ear were testimony to his role in a great military triumph. At the battle of Worcester, the Royalist army had been emphatically routed.

'What a day that was!' recalled Sir Julius Cheever.

'One of the proudest of my life,' said Everett.

'Even though it was very nearly your last.'

'God was there to save me, Sir Julius.'

'Had you kept it on, your helmet would have done that. And it would have left you looking a trifle prettier.'

'Who cares what I look like? We won the battle.'

'Yes,' said Sir Julius. 'That's what really mattered.'

Bernard Everett was a stocky man of middle years and medium height. His short grey hair surmounted a bulbous forehead. A pleasant face had been given a sinister quality by the hideous battle scar. Everett had served under Sir Julius Cheever in the army, and he was glad to be reunited with his old colonel. He was even more delighted by his recent election as Member of Parliament for Cambridge, a city that Oliver Cromwell, a man he revered, had represented in parliament.

Military service was not the only link between the two men. Sir Julius, too, was a Member of Parliament, representing his native county of Northamptonshire, and bringing a bold and uncompromising voice to any debate. Big, bulky, opinionated and forthright, he was sixty years old but he had lost very little of his vigour and he remembered, in precise detail, the experiences that he and Bernard Everett had shared on various battlefields during the Civil War.

'They fought well at Worcester,' he conceded, 'but we had the beating of them from the start. We had thirty thousand soldiers in the field.'

'Our army and militia were out in force,' recalled Everett.

'The Royalists were hopelessly outnumbered.'

'How many prisoners did we take, Sir Julius?'

'The best part of ten thousand,' said the other, 'in addition to the three thousand that were killed in action. Of course, we did have casualties on our side.'

Everett chuckled. 'I know - I was one of them.'

'Are you two still talking about the war?' asked Hester Polegate, clicking her tongue in disapproval. 'That's all in the past. It's time to look to the future, Bernard. Now come and see the rest of the house.'

'Gladly, Hester.'

'You, too, Sir Julius.'

Everett gave her a conciliatory kiss on the cheek. Hester Polegate was his sister, a plump woman in her late forties with a round, rosy-cheeked face and a genial manner. She took her duties as hostess very seriously. Along with others, her brother had been invited to celebrate the opening of the new business in Knightrider Street. Hester's husband, Francis Polegate, a lean, angular man, was a successful wine merchant who had been looking for new premises. He had purchased a corner site then searched for someone to design the building.

Sir Julius Cheever was a good friend of Polegate's and he had recommended a name to him. As a result, Christopher Redmayne, the young architect who had designed Sir Julius's own house in London, was given the commission. He, too, was present on the day that the merchant and his family took over their new quarters. It was a happy occasion. Christopher was not only pleased to receive endless praise from satisfied clients. He had an opportunity to spend time with the other guest, Susan Cheever, daughter of Sir Julius, the lovely young woman with whom the architect had an understanding that was slowly moving towards a formal betrothal. While everyone else was being shown around the building, he preferred to stay in the hall with Susan.

'It's a lovely house, Christopher,' she said. 'You worked hard on the plans. I'm so grateful that I'm able to see the final result. You have every right to be proud of your achievement.'

'Thank you.'

'Mr and Mrs Polegate are thrilled.'

'Yours is the only opinion I really value, Susan.'

'Then you have my unstinting approval.'

'But you haven't seen the house properly yet.'

'I don't need to,' she said. 'Everything that Christopher Redmayne designs has the hallmark of excellence.'

He laughed. Christopher was tall, lithe and handsome with long, curly hair that had a reddish tinge. Though conspicuously well-dressed, he wore none of the garish apparel that was so popular among younger men. There was an air of restraint about him that appealed to Susan. For his part, Christopher had been drawn to her from the moment they had first met. Slim and shapely, Susan had a bewitching face and the most beautiful skin he had ever seen. Sir Julius was a wealthy farmer and, for all his eminence, there was a distinctly rustic air about him. His daughter had not inherited it. She could have passed for a court beauty.

'This is the finest room in the house,' he explained, glancing around the hall. 'As you've seen, the living quarters are all on the first floor and I included a gallery that leads to further rooms over the back kitchen. The shop is at the front of the property, of course, with merchandise housed in the cellars and the warehouse. Mr Polegate imports wine from other countries so he needs plenty of space to store it. His counting house is over the main kitchen. The bedrooms are on the floor above us,' he went on, pointing upwards, 'with dormer windows in the roof - tiled, naturally. Since the Great Fire, nobody uses thatch.'

'The whole building is so compact,' she observed.

'When you have a limited area, you have to create extra height.'

'There's even a yard with its own well.'

'That's a valuable feature of the house, Susan. If it were not raining so hard,' he added, looking through the windows at the storm raging outside, 'I'd show you the yard. It's beautifully cobbled.'

'Clearly, no expense has been spared.'

'More to the point, my clients have paid both architect and builder. That's not always the case, believe me. With some projects, I've waited up to a year for my fee.'

'You should ask for more money in advance.'

'People are not always in a position to pay it.' He heard footsteps in the room above his head and moved closer to her. 'Before the others come back, I wanted to ask you about your father. Why does he seem so uncommonly contented?'

'Contented?'

'Sir Julius is truculent as a rule.'

'That's just his way, Christopher. Father is always rather blunt.'

'He's positively joyful today.'

'I think he's pleased to meet Mr Everett again.'

'It goes deeper than that,' said Christopher. 'There was a moment earlier on when I caught him standing at the window, staring out with a broad smile on his face. He was completely lost in thought. Something has obviously brought happiness into his life.'

Susan was almost brusque. 'It's not happiness,' she said with a dismissive wave of her hand. 'Father hates idleness. Now that parliament has been recalled, he'll be employed again and that's what he enjoys most. He thrives on the rough and tumble of debate.'

Christopher had a feeling that the mellowing of Sir Julius Cheever had nothing to do with parliament, an institution whose activities, more often than not, tended to enrage him beyond measure. Nor could his reunion with Bernard Everett explain his uncharacteristic mildness. It had another source. In trying to find out what it was, Christopher had unwittingly thrown Susan on the defensive. He regretted that. Not wishing to upset her any further, he abandoned the subject altogether.

Having inspected the upper rooms, the others rejoined them in the hall. Food and wine had been set out on the long oak table and a servant handed the refreshments out to the guests, Everyone was very complimentary about the house and shop. Christopher basked in their approbation. Since it was a purely functional property, it had not been the most exciting commission of his career but it had won him new admirers and would act as a clear advertisement for his talents. Sir Julius had passed on his name to Francis Polegate. Christopher hoped that Polegate would, in turn, speak up on his behalf to others.

Calling for silence, the wine merchant raised his glass.

'I think that we should toast the architect,' he said.

'The architect,' responded the others in unison. 'Mr Redmayne!'

'Thank you,' said Christopher, modestly, 'but we must not forget the builder. Without him, an architect would be lost.'

'Without you,' Polegate noted, 'a builder would be unemployed.'