The Palace of Illusions (2 page)

Like many Indian children, I grew up on the vast, varied, and fascinating tales of the

Mahabharat.

Set at the end of what the Hindu scriptures term Dvapar Yug or the Third Age of Man (which many scholars date between 6000 BCE and 5000 BCE), a time when the lives of men and gods still intersected, the epic weaves myth, history, religion, science, philosophy, superstition, and statecraft into its innumerable stories-within-stories to create a rich and teeming world filled with psychological complexity. It moves with graceful felicity between the very recognizable human world and magical realms where yakshas and apsaras roam, depicting these with such exquisite surety that I would often wonder if indeed there was more to existence than what logic and my senses could grasp.

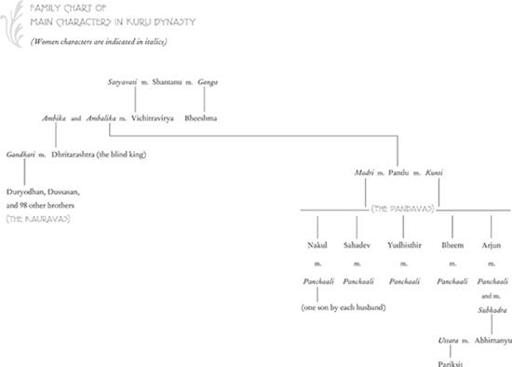

At the core of the epic lies the fierce rivalry between two branches of the Kuru dynasty, the Pandavas and the Kauravas. The lifelong struggle between the cousins for the throne of Hastinapur culminates in the bloody battle of Kurukshetra, in which most kings of that period participated and perished. But numerous other characters people the world of the

Mahabharat

and contribute to its magnetism and continuing relevance. These larger-than-life heroes, epitomizing inspiring virtues and deadly vices, etched many cautionary morals into my child-consciousness. Some of my favorites, who play prominent roles in

The Palace of Illusions,

are: Vyasa the sage, at once the composer of the epic and a participant at crucial moments in the action; Krishna, beloved and inscrutable, an incarnation of Vishnu and mentor to the Pandavas; Bheeshma, the patriarch who, bound by his promise to protect the Kuru throne, must fight against his beloved grandsons; Drona, the brahmin-warrior who becomes teacher to both the Kaurava and Pandava princes; Drupad, the king of Panchaal, whose desire for vengeance against Drona activates the wheel of destiny; and Karna, the great warrior, who is doomed because he does not know his parentage.

But always, listening to the stories of the

Mahabharat

as a young girl in the lantern-lit evenings at my grandfather's village home, or later, poring over the thousand-page leather-bound volume in my parents' home in Kolkata, I was left unsatisfied by the portrayals of the women. It wasn't as though the epic didn't have powerful, complex women characters that affected the action in major ways. For instance, there was the widowed Kunti, mother of the Pandavas, who dedicates her life to making sure her sons became kings. There was Gandhari, wife of the sightless Kaurava king, who chooses to blindfold herself at marriage, thus relinquishing her power as queen and mother. And most of all, there was Panchaali (also known as Draupadi), King Drupad's beautiful daughter, who has the unique distinction of being married to five men at the same time—the five Pandava brothers, the greatest heroes of their time. Panchaali who, some might argue, by her headstrong actions helps to bring about the destruction of the Third Age of Man. But in some way, they remained shadowy figures, their thoughts and motives mysterious, their emotions portrayed only when they affected the lives of the male heroes, their roles ultimately subservient to those of their fathers or husbands, brothers or sons.

If I ever wrote a book, I remember thinking (though at that time I didn't really believe this would ever happen), I would place the women in the forefront of the action. I would uncover the story that lay invisible between the lines of the men's exploits. Better still, I would have one of them tell it herself, with all her joys and doubts, her struggles and her triumphs, her heartbreaks, her achievements, the unique female way in which she sees her world and her place in it. And who could be better suited for this than Panchaali?

It is her life, her voice, her questions, and her vision that I invite you into in

The Palace of Illusions.

A

SWATTHAMA

: Drona's son

D

HRISTADYUMNA

: Brother of Panchaali (often referred to as Dhri)

D

RONA

: Teacher of warcraft for the Kaurava and Pandava princes; teacher of Dhristadyumna

D

RUPAD

: King of Panchaal, father of Panchaali (Draupadi) and her twin brother Dhristadyumna; onetime friend and now enemy of Drona

K

ARNA

: Best friend of Duryodhan and rival of Arjun; king of Anga; as an infant he was discovered floating on the Ganga river and was brought up by Adhiratha the chariot driver

K

EECHAK

: Sudeshna's brother and commander of the Matsya army

K

RISHNA

: Incarnation of the god Vishnu; ruler of the Yadu clan; mentor to the Pandavas and Arjun's best friend; dear friend to Panchaali; brother of Subhadra, who marries Arjun

S

UDESHNA

: Virat's queen; Uttara's mother

V

IRAT

: Aged king of Matsya; Uttara's father

V

IDUR

: Chief minister of Dhritarashtra and friend to the orphaned Pandavas

V

YASA

: Omniscient sage and composer of the

Mahabharat

who also appears in it as a character

1

Through the long, lonely years of my childhood, when my father's palace seemed to tighten its grip around me until I couldn't breathe, I would go to my nurse and ask for a story. And though she knew many wondrous and edifying tales, the one I made her tell me over and over was the story of my birth. I think I liked it so much because it made me feel special, and in those days there was little else in my life that did. Perhaps Dhai Ma realized this. Perhaps that was why she agreed to my demands even though we both knew I should be using my time more gainfully, in ways more befitting the daughter of King Drupad, ruler of Panchaal, one of the richest kingdoms in the continent of Bharat.

Through the long, lonely years of my childhood, when my father's palace seemed to tighten its grip around me until I couldn't breathe, I would go to my nurse and ask for a story. And though she knew many wondrous and edifying tales, the one I made her tell me over and over was the story of my birth. I think I liked it so much because it made me feel special, and in those days there was little else in my life that did. Perhaps Dhai Ma realized this. Perhaps that was why she agreed to my demands even though we both knew I should be using my time more gainfully, in ways more befitting the daughter of King Drupad, ruler of Panchaal, one of the richest kingdoms in the continent of Bharat.

The story inspired me to make up fancy names for myself: Offspring of Vengeance, or the Unexpected One. But Dhai Ma puffed out her cheeks at my tendency to drama, calling me the Girl Who Wasn't Invited. Who knows, perhaps she was more accurate than I.

This winter afternoon, sitting cross-legged in the meager sunlight that managed to find its way through my slit of a window, she said, “When your brother stepped out of the sacrificial fire onto the cold stone slabs of the palace hall, all the assembly cried out in amazement.”

She was shelling peas. I watched her flashing fingers with envy,

wishing she would let me help. But Dhai Ma had very specific ideas about activities that were appropriate for princesses.

“An eyeblink later,” she continued, “when you emerged from the fire, our jaws dropped. It was so quiet, you could have heard a housefly fart.”

I reminded her that flies do not perform that particular bodily function.

She smiled her squint-eyed, cunning smile. “Child, the things you don't know would fill the milky ocean where Lord Vishnu sleeps—and spill over its edges.”

I considered being offended, but I wanted to hear the story. So I held my tongue, and after a moment she picked up the tale again.

“We'd been praying for thirty days, from sun-up to sundown. All of us: your father, the hundred priests he'd invited to Kampilya to perform the fire ceremony, headed by that shifty-eyed pair, Yaja and Upayaja, the queens, the ministers, and of course the servants. We'd been fasting, too—not that we were given a choice—just one meal, each evening, of flattened rice soaked in milk. King Drupad wouldn't eat even that. He only drank water carried up from the holy Ganga, so that the gods would feel obligated to answer his prayers.”

“What did he look like?”

“He was thin as the point of a sword, and hard like it, too. You could count every bone on him. His eyes, sunk deep into their sockets, glittered like black pearls. He could barely hold up his head, but of course he wouldn't remove that monstrosity of a crown that no one has ever seen him without—not even his wives, I've heard, not even in bed.”

Dhai Ma had a good eye for detail. Father was, even now, much the same, though age—and the belief that he was finally close to getting what he'd wanted for so long—had softened his impatience.