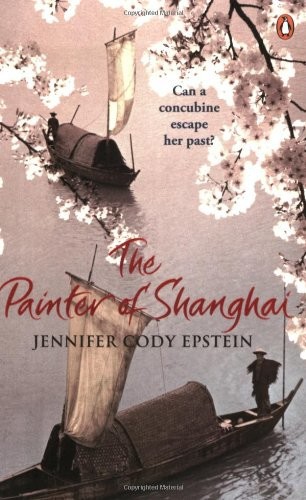

The Painter of Shanghai

The Painter of Shanghai

JENNIFER CODY EPSTEIN

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196,

South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the USA as

The Painter From Shanghai

by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

First published in Great Britain in Penguin Books 2008

1

Copyright © Jennifer Cody Epstein, 2008

The permissions on pp.

486-7

constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-191749-8

For Michael.

For everything.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

While this novel is based on the life and works of Pan Yuliang, it is a work of the imagination. It attempts to stay true to the broad strokes of Madame Pan’s life as depicted in the few sources available. For the most part, however, the characters, events, and places depicted here are – like the paintings that inspired them – impressionistic portraits.

Here is a sketch by Leonardo da Vinci. I enter this sketch

and I see him at work and in trouble and I meet him there.

Robert Henri

The Art Spirit

PART ONE

The Atelier

Though a living cannot be made at art, art makes life worth living.

It makes starving, living. It makes worry, it makes trouble, it

makes a life that would be barren of everything – living. It brings

life to life.

John Sloan

Montparnasse, 1957

When the session is over, Yuliang retreats to the chipped sink in the atelier’s corner. Of her two models, one leaves immediately. The other, Leanne, lingers a little, straightening her slip and shimmying her garters back into place high on her thighs. As she hooks the straps to her stockings, she leans over Yuliang’s painting and the still-damp fruits of the past five hours: a tree, a lake. Herself kneeling by another nude.

Wiping her spattered palms on her painting smock, Yuliang observes Leanne observing the girl she has just been made into. She did well today, Yuliang decides. New models often need extra time to undress, to settle into their nudity before strangers. But Leanne surprised her, stepping out of her Orlon shift and underwear as blithely as though she’d undressed publicly all her life. She didn’t fuss over her flesh; didn’t apologize for or try to hide the pimple on her left thigh. But at each break in the five-hour session she crossed the room and, still unabashedly naked, silently inspected Yuliang’s progress.

Yuliang, who usually works through her model’s rest times, found these attentions disconcerting. She didn’t stop working. But she worked differently than she’d planned, reluctant to retouch the girl’s painted flesh under her real-life gaze. She worked on other things – her willow tree, the rumpled blanket – all the while inhaling her

observer’s scent: her cheap perfume, her old smokes, a sour-sweet hint of sweat. Something clean and cloverlike too, like sun-dried sheets. Leanne has said that her father runs a laundry shop near the Gare de Lyon.

Water rushes from the faucet, rust-flecked. Yuliang waits, fingertips pressing the soap-filmed chill of the tap. When the stream runs pure, she pushes her brushes beneath it. Colors wash into their neutralizing counterparts: ultramarine into cadmium into blue into yellow ocher, the brilliant shades blending into a mud-toned flow that disappears down the drain.

She is starting on her hands when Leanne sneezes, a breathy explosion so high-pitched it’s almost sweet.

‘

Pardon

,’ Leanne says.

‘

Non, non

,’ says Yuliang. ‘I’m sorry it’s so cold in here.’ She says it in French; Leanne’s Chinese is, she’s found, limited.

‘The cat, perhaps. Sometimes they make my nose itch.’ The girl presses a handkerchief against her upper lip.

‘Ah.’ Yuliang turns back to her brushes, the cloth momentarily etched in her mind’s eye: the starry whiteness, the sheen endowed by hot iron and starch. Leanne’s family, from Guangxi originally, ran one of Hanoi’s Chinese banks until ’54. Leanne hasn’t offered more than this; Yuliang assumes the Communists took the bank when they took the rest of the north.

Does she miss it?

she wonders.

For she herself certainly misses China – despite everything. ‘Do you consider going home?’ a reporter asked her at her last exhibition. ‘

Naturellement, parfois

,’ she replied, although in truth she ‘considers’ it all the time. The truth

is, ‘home’ feels less like a place now than an inner part of her, an organ cancerously riddled with longing. The hurt recedes when she’s painting. But the ache of it, of all she’s lost – that never leaves. Places and people still appear in an eyeblink, so tremblingly real she could touch them. The Parisian grace of Fouzhou Road, its elm-lined streets and Tudor mansions. A Shanghai marketplace, its air saturated with dialects and the fierce smell of seared meat. Women washing food and dishes on a riverbank, nursing their howling red babies. The damp clatter of Yangtze commerce, its endlessly inventive curses.

She shuts her eyes. In an instant she is back on the steamship landing, Zanhua’s arms stiff and desperate around her, that ridiculous cane poking right into her shoulder blade. It seemed so clear to her then – back in 1937 – that Chiang Kai-shek’s so-called New Life was already half dead. Chaipei lay in charred ruins. Hirohito’s soldiers roamed Shanghai like wolves circling before another attack. But the true danger came from Yuliang’s own countrymen, Chiang’s Blue Shirts and Green Gang thugs – the Generalissimo’s own oppressive little palette. Everyone knew at that point that Yuliang was a marked target – if not her body, then certainly her work. And yet Zanhua still begged her to reconsider.

You can stay,

he’d insisted.

It’s not too late. Things here are on the verge of change. I feel it.

Even now – is it really twenty full years later? – Yuliang all but hears his voice. And for just an instant, doubt wells.

Should

she have stayed?

Don’t be ridiculous.

Opening her eyes, Yuliang shuts off the emotion as ruthlessly as she twists shut the tap. Her work is her life. She is lonely here, yes. But she has her

painting, her cats. Her clients and admirers. Her small circle of intimates. Each one would confirm that her decision was the right one. Her friend Junbi said as much the other day, studying Yuliang’s latest self-portrait: ‘There’s something new in this one.’

‘You mean the fact that I’ve shown myself smoking, gambling,

and

drinking?’ Yuliang didn’t mention the nudity. Of course, that’s not new.

‘That’s not it.’ Junbi thought for a moment, her soft brow furrowed. ‘Ah! I see it now. You are smiling. You actually look happy.’

‘Oh, really.’ But staring at herself – the flushed face, the round contours, the unusually relaxed stance, Yuliang had to admit she saw it too: she looked, at last, like a woman enjoying her life.

Her reverie is interrupted by the bells of Chapelle des Auxiliatrices. She looks at her watch, then up at Leanne, still standing in stocking feet by the table. Has the girl really been here for an entire half-hour?

As though hearing Yuliang’s unspoken groan, Leanne steps back from the painting. She is chewing her lower lip.

‘Is something wrong?’ Yuliang asks her.

‘My legs. You’ve made them – how do I put it? Rather… fat.’

Ah-ha

. So that’s what she’s been mooning around for. ‘I apologize,’ Yuliang says curtly. And yet even as she says it, she sees in the girl’s face that it isn’t that, isn’t vanity after all. It is simply a question.

Why? Why did you do it this way?

It is not Yuliang’s habit to explain her art. Not to critics.

Certainly not to models. Nevertheless, she finds herself stepping to the girl’s side. ‘

Alors

,’ she says, and with her brush handle traces over the painting’s surface. Three lines: from Leanne’s thigh to the tip of her head; from her head to Xiahe’s buttocks; finally, along Xiahe’s outstretched leg to the toe that nestles against Leanne’s bare knee. ‘They are not your legs alone. They’re legs for the compositional structure. A triangle. See? If I make them too thin, it throws off the balance. Even the lines are thick. You know some calligraphy?’ And when the girl shakes her head: ‘Well, if you did, you’d recognize the stroke. It’s very similar to those used in scrolls.’

Leanne drops her gaze to the floor. She twists a foot into a patent-leather pump. Yuliang follows the movement musingly. Then she does the one thing she absolutely should not do at this instant: she looks back at her picture.

What she sees sinks her spirits: a hundred flaws bloom. Brushstrokes that seemed precise a half-hour ago shapeshift into gaping mistakes. The willow tree is flaccid. Leanne’s hair – painted, she had thought, so as to create a sense of translucence – now simply appears to be stringy. And, yes, no doubt about it – the girl’s legs are too thick.

Defeated, she leans against the table.

I’m a farce,

she thinks.

Even after all these years…

‘Madame. Are you all right?’

With her shoes on, Leanne stands a good seven centimeters above her. For a moment there’s an urge to throw her arms around the white neck, to confess. To weep. But then Leanne touches her arm, and Yuliang stiffens as she always does when touched without permission.

‘We said five francs, correct?’ She picks up her purse, snaps it open, and offers the bills stiffly. Leanne blinks.

‘Thank you,’ she says, and takes the fee. There’s an uncomfortable pause. ‘I like your purse,’ she adds.

Yuliang smiles coolly. The girl turns to pick up her salmon swing coat. ‘Tomorrow at eleven again?’

‘Tomorrow we rest.’ Yuliang says, although in fact she’s only just made this decision. She will take a day alone. To repair the damage. ‘Come Friday at four.’ And when Leanne hesitates, ‘Friday is no good?’

‘No, it’s fine. I finish with my father at three.’

‘Good.’ Yuliang reseats herself. It is late. What she wants is to smoke, to lose herself in the soothing, circular work of ink-grinding. But she has a student coming at six, one of the boys from the Beaux Arts. A baby, but very handsome: a liquid-eyed Italian. He indulges her by letting her attempt to instruct him in his native language – although these days Yuliang’s Italian surely isn’t much better than his Chinese.

She fumbles for her Gitanes, awaiting the woolly rustle of Leanne’s coat, the calm

click

of the door closing. When neither comes she glances at the small mirror she’s hung opposite the door (less to deflect spirits than to detect their more annoying mortal counterparts). The mirror reveals Leanne, still at the threshold, one gloved hand on the knob.