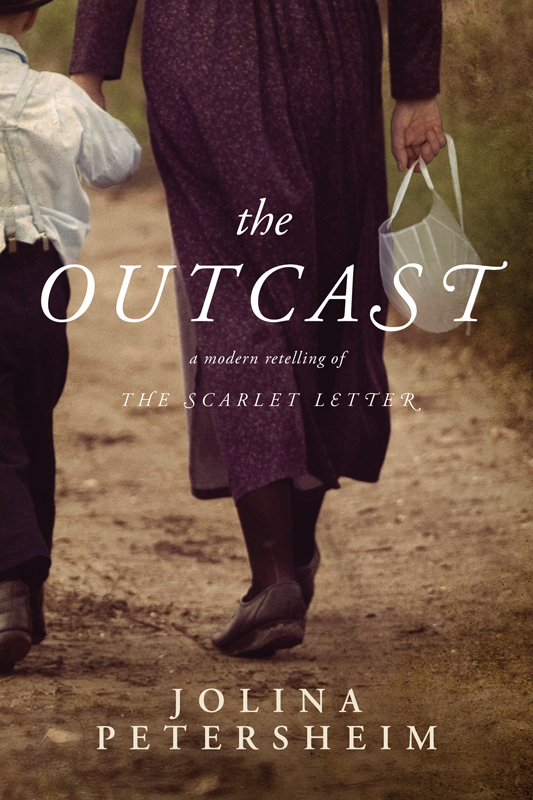

The Outcast

Authors: Jolina Petersheim

Tags: #FICTION / Christian / General, #FICTION / General

The Outcast

“A must-read that will draw you into a secretive world of sin and senselessness and leave you with the hope of one set free.”

JULIE CANTRELL

New York Times

bestselling author of

Into the Free

“Surprising and satisfying, this epic first novel of love and betrayal, forgiveness and redemption will resonate with people from every corner of life.”

RIVER JORDAN

Bestselling author of

Praying for Strangers: An Adventure of the Human Spirit

“

The Outcast

is an insightful look at the complexities of living in community while living out one’s faith.”

KAREN SPEARS ZACHARIAS

Author of

Will Jesus Buy Me a Doublewide? ’cause I need more room for my plasma TV

“[This] riveting portrait of life behind this curious and ofttimes mysterious world captivated me from the first word and left me breathless for more. Do yourself a favor and place

The Outcast

at the top of your reading list.”

LISA PATTON

Bestselling author of

Whistlin’ Dixie in a Nor’easter

“From the first word until the last,

The Outcast

captivates and charms, reminding us that forgiveness and love are two of life’s greatest gifts. A brilliant must-read debut novel.”

RENEA WINCHESTER

Author of

In the Garden with Billy:

Lessons about Life, Love & Tomatoes

Visit Tyndale online at

www.tyndale.com

.

Visit Jolina Petersheim online at

www.jolinapetersheim.com

.

TYNDALE

and Tyndale’s quill logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

The Outcast

Copyright © 2013 by Jolina Petersheim. All rights reserved.

Cover photograph of mother and child copyright © Aaron Mason/ Getty Images. All rights reserved.

Cover photograph of kapp taken by Stephen Vosloo. Copyright © by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved.

Designed by Dean H. Renninger

Edited by Kathryn S. Olson

Published in association with Ambassador Literary Agency, Nashville, TN.

Scripture taken from the Holy Bible,

New International Version

,

®

NIV

.

®

Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.

™

Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide.

www.zondervan.com

.

The Outcast

is a work of fiction. Where real people, events, establishments, organizations, or locales appear, they are used fictitiously. All other elements of the novel are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Petersheim, Jolina.

The outcast / Jolina Petersheim.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-4143-7934-0 (sc)

1. Mennonites—Fiction. 2. Single women—Fiction. 3. Christian fiction. I. Title.

PS3616.E84264O97 2013

813'.6—dc23 2012048725

ISBN 978-1-4143-8605-8 (ePub); ISBN 978-1-4143-8391-0 (Kindle); ISBN 978-1-4143-8606-5 (Apple)

Build: 2013-09-16 10:45:29

To my kindred spirit, Misty, the bravest person I know.

I love you to life, friend.

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- A Preview of The Midwife

- A Note from the Author

- About the Author

- Discussion Questions

From the beautiful

teacher who helped a struggling seven-year-old read

Lassie Come-Home

, to the compassionate professor who read my first manuscript and kindly told me it was not yet time, all my life I have been surrounded by a village of supporters who have helped raise this child, my novel.

Firstly, I want to thank my parents, who provided me with a childhood devoid of TV and teeming with books and silver minnows in shallow creeks and acres of deep woods to explore. You both have calloused hands so that I can now callous these fingertips pressing a keyboard. Thank you for your sacrifice and for never doubting my ability to write, even when I doubted it myself. I love you both from the bottom of my heart, and I pray I will be as great a supporter of my daughter’s dreams.

I would like to thank the patient instructors who have gone above and beyond the call of duty to streamline this superfluous writer: Carey Boggs, Brent Coley, Regina Blazer, Gina Herring, Tom and Kathy Fish, Marianne Worthington. All writing accolades are yours; all compound modifiers are mine.

A humble thank-you to my friends who have supported me through reading, listening, editing, endorsing, and hooking my

feet back into the stirrups whenever I got bucked off: Susie and Carl Roberts, Chris Peters, Joanne Petersheim, Chris Painter, Paige Crutcher, Kat Wood, Katie Rulketter, Jessi Buck, Candace Smith, Crystal Hillis, Hannah Alaniz, Kaitlin Alms Belcher, Rebekah Mason, Niki Cecil, Brenda McClain, Melissa Crytzer-Fry, Kimberly Brock, Julia Monroe Martin, Cynthia Robertson, Erika Robuck, Erika Marks, Renea Winchester, Shellie Rushing Tomlinson, Karen Spears Zacharias, Julie Cantrell.

To my dear mother-in-law: Thank you for your example of unconditional love and for telling me that this story needed to be told. Thank you, also, for watching Baby Girl and bringing over that pan of lasagna while I was on deadline.

Thank you, Nancy Jensen, for turning your creative writing classes into something akin to therapy. I don’t know what I would have done that difficult semester without your cups of Bigelow tea and grace-filled words.

Wes Yoder: Thank you for agreeing to represent this story that unveils a hidden side of our Plain heritage. I know it was a risk for a seasoned agent to take on an untried writer, and I am honored to be working with you.

Thank you, Misty Brianne Adams, for letting me read my journal entries to you from the time I was in sixth grade until college, and for taking long walks with me while I untangled plot snarls. Thank you, also, for just being you—a compassionate, loving woman who faces life with a quiet peace concealing the strength of William Wallace, to which Vanderbilt doctors will attest. You have his sword, after all.

River Jordan: Thank you,

thank you

for taking this trembling fledgling under your wings and inviting me to lunches and other events where you introduced me to a community of loving writers and friends. I would not be here if it weren’t for you; I am so glad I clogged that night.

To the Tyndale fiction team composed of Karen Watson, Kathy Olson, Stephanie Broene, Shaina Turner, Babette Rea, and Dean Renninger: You all work with an efficiency that turns this convoluted publishing process into a joy. I cannot think of anyplace I would rather be.

To my firstborn child, my daughter: It was no coincidence that your birth took place during the birth of my novel. You are my magnum opus, my life’s work, and I pray that I will continue to put your precious life before my art. But that through my art, you will also find the courage to follow your dreams. I will love you always.

To my beloved husband and the father of my child: You are my bulwark and my sails. Thank you for supporting my dreams day in and day out and for saying the laptop’s glow didn’t bother you when you were trying to sleep at night. Life with you has been an incredible adventure, and I cannot wait to see what others are in store. I love you so very much.

To my Savior: Thank you for planting in my heart the seed for story. I pray that I will have the discernment to root out the ones you don’t want told and nourish the ones you do. May I draw closer to you during their telling, and may my readers draw closer to you in their reading. Keep my knees bent, my heart open, and my gaze fixed solely on you.

To the unsung prophet of the London Underground: I believe our meeting was not happenstance, but divinely appointed, as your word that I would abandon my current manuscript and write one that was God-inspired has come to pass. Strange how I had to travel overseas just to hear one still small voice amid the clamor of so many others. Thank you for letting him speak through you.

Rachel

Rachel

My face burns with the heat of a hundred stares. No one is looking down at Amos King’s handmade casket because they are all too busy looking at me. Even Tobias cannot hide his disgust when he reaches out a hand, and then realizes he has not extended it to his angelic wife, who was too weak to come, but to her fallen twin. Drawing the proffered hand back, Tobias buffs the knuckles against his jacket as if to clean them and slips his hand beneath the Bible. All the while his black eyes remain fixed on me until Eli emits a whimper that awakens the new bishop to consciousness. Clearing his throat, Tobias resumes reading

from the German Bible: “‘Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death . . .’”

I cannot help but listen to such a well-chosen verse, despite the person reading it. I feel I am walking through the valley of death even as this new life, my child, yawns against my ribs. Slipping a hand beneath Eli’s diapered bottom, I jiggle him so that his ribbon mouth slackens into a smile. I then glance across the earthen hole and up into Judah King’s staring, honey-colored eyes. His are softer than his elder brother Tobias’s: there is no judgment in them, only the slightest veiling of confusion not thick enough to hide the pain of his unrequited love, a love I have been denying since childhood.

Dropping my gaze, I recall how my braided pigtails would fly out behind me as I sprinted barefoot down the grassy hill toward ten-year-old Judah. I remember how he would scream,

“Springa! Springa!”

and instead of being caught by Leah or Eugene or whoever was doing the chasing, I would run right toward the safety of base and the safety of him. Afterward, the two of us would slink away from our unfinished chores and go sit in the milking barn with our sweat-soaked backs against the coolness of the storage tanks. Judah would pass milk to me from a jelly jar and I would take a sip, read a page of the Hardy Boys or the Boxcar Children, and then pass his contraband book and jelly jar back.

Because of those afternoons, Judah taught me how to speak, write, and read English far better and far earlier than

our Old Order Mennonite teachers ever could have. As our playmates were busy speaking Pennsylvania Dutch, Judah and I had our own secret language, and sheathed in its safety, he would often confide how desperately he wanted to leave this world for the larger one beyond it. A world he had explored only through the books he would purchase at Root’s Market when his father wasn’t looking and read until the pages were sticky with the sweat of a thousand secret turnings.

Summer was slipping into fall by the time my

mamm

, Helen, discovered our hiding spot. Judah and I had just returned from making mud pies along the banks of the Kings’ cow pond when she stepped out of the fierce sun into the barn’s shaded doorway and found us sitting, once again, beside the milking tanks with the fifth book in the Boxcar Children series draped over our laps. Each of us was so covered in grime that the jelly jar from which we drank our milk was marred with a lipstick kiss of mud. But we were pristine up to the elbows, because Judah feared we would damage his book’s precious pages if we did not redd up before reading them.

That afternoon, all my

mamm

had to do was stand in the doorway of the barn with one hand on her hip and wag the nubby index finger of her other hand (nubby since it had gotten caught in the corn grinder when she was a child), and I leaped to my feet with my face aflame.

For hours and hours afterward, my stomach churned. I thought that when

Dawdy

got home from the New

Holland horse sales he would take me out to the barn and whip me. But he didn’t.

To this day, I’m not even sure

Mamm

told him she’d caught Judah and me sitting very close together as we read from our

Englischer

books. I think she kept our meeting spot a secret because she did not want to root out the basis of our newly sprouted friendship, which she hoped would one day turn into fully grown love. Since my

mamm

was as private as a woman in such a small community could be, I never knew these were her thoughts until nine years later when I wrote to tell her I was with child.

She arrived, haggard and alone, two days after receiving my letter. When she disembarked from the van that had brought her on the twelve-hour journey from Pennsylvania to Tennessee, she walked with me into Leah and Tobias’s white farmhouse, up the stairs into my bedroom, and asked in hurried Pennsylvania Dutch, “Is Judah the

vadder

?”

Shocked, I just looked at her a moment, then shook my head.

She took me by the shoulders and squeezed them until they ached. “If not him, who?”

“I cannot say.”

“What do you mean, you cannot say? Rachel, I am your

mudder

. You can trust me,

jah

?”

“Some things go beyond trust,” I whispered.

My

mamm

’s blue eyes narrowed as they bored into mine. I wanted to look away, but I couldn’t. Although I was nineteen, I felt like I was a child all over again, like she still held

the power to know when I had done something wrong and who I had done it with.

At last, she released me and dabbed her tears with the index nub of her left hand. “You’re going to have a long row to hoe,” she whispered.

“I know.”

“You’ll have to do it alone. Your

dawdy

won’t

let you come back . . . not like this.”

“I know that, too.”

“Did you tell Leah?”

Again, I shook my head.

My

mamm

pressed her hand against the melon of my stomach as if checking its ripeness. “She’ll find out soon enough.” She sighed. “What

are you? Three months, four?”

“Three months.” I couldn’t meet her eyes.

“Hide it for two more. ’Til Leah and the baby are stronger. In the meantime, you’ll have to find a place of your own. Tobias won’t

let you stay here.”

“But where will I go? Who will take me in?” Even in my despondent state, I hated the panic that had crept into my voice.

My

mamm

must have hated it as well. Her nostrils flared as she snapped, “You should’ve thought of this before, Rachel! You have sinned in haste. Now you must repent at leisure!”

This exchange between my

mamm

and me took place eight months ago, but I still haven’t found a place to stay. Although the Mennonites do not practice the shunning

enforced by the Amish

Ordnung

, anyone who has joined the Old Order Mennonite church as I had and then falls outside its moral guidelines without repentance is still treated with the abhorrence of a leper. Therefore, once the swelling in my belly was obvious to all, the Copper Creek Community, who’d welcomed me with such open arms when I moved down to care for my bedridden sister, began to retreat until I knew my child and I would be facing our uncertain future alone. Tobias, more easily swayed by the community than he lets on, surely would have cast me and my bastard child out onto the street if it weren’t for his wife. Night after night I would overhear my sister in their bedroom next to mine, begging Tobias, like Esther beseeching the king, to forgive my sins and allow me to remain sheltered beneath their roof—at least until after my baby was born.

“Tobias, please,” Leah would entreat in her soft, high-pitched voice, “if you don’t want to do it for Rachel, then do it for

me

!”

Twisting in the quilts, I would burrow my head beneath the pillow and imagine my sister’s face as she begged her husband: it would be as white as the cotton sheet on which I lay, her cheeks and temples hollowed at first by chronic morning sickness, then later—after Jonathan’s excruciating birth—by the emergency C-section that forced her back into the prison bed from which she’d just been released.

Although I knew everything external about my twin, for in that way she and I were one and the same, lying

there as Tobias and Leah argued, I could not understand the internal differences between us. She was selfless to her core—a trait I once took merciless advantage of. She would always take the drumstick of the chicken and give me the breast; she would always sleep on the outside of the bed despite feeling more secure against the wall; she would always let me wear her new dresses until a majority of the straight pins tacking them together had gone missing and they had frayed at the seams.

Then, the ultimate test: at eighteen Leah married Tobias King. Not out of love, as I would have required of a potential marriage, but out of duty. His wife had passed away five months after the birth of their daughter Sarah, and Tobias needed a

mudder

to care for the newborn along with her three siblings. Years ago, my family’s home had neighbored the Kings’. I suppose when Tobias realized he needed a wife to replace the one he’d lost, he recalled my docile, sweet-spoken twin and wrote, asking if she would be willing to marry a man twelve years her senior and move away to a place that might as well have been a foreign land.

I often wonder if Leah said yes to widower Tobias King because her selfless nature would not allow her to say no. Whenever she imagined saying no and instead waiting for a union with someone she might actually love, she would probably envision those four motherless children down in Tennessee with the Kings’ dark complexion and angular build, and her tender heart would swell with compassion and the determination to marry a complete stranger.

I think, at least in the back of her mind, Leah also knew that an opportunity to escape our yellow house on Hilltop Road might not present itself again. I had never wanted for admirers, so I did not fear this fate, but then I had never trembled at the sight of a man other than my father, either. As far back as I can recall, Leah surely did, and I remember how I had to peel her hands from my forearms as the wedding day’s festivities drew to a close, and

Mamm

and I finished preparing her for her and Tobias’s final unifying ceremony.

“

Ach

, Rachel,” she stammered, dark-blue eyes flooded with tears. “I—I can’t.”

“You goose,” I replied, “

sure

you can! No one’s died from their wedding night so far, and if all these children are a sign, I’d say most even like it!”

It was a joy to watch my sister’s wan cheeks burn with embarrassment, and that night I suppose they burned with something entirely new. Two months later she wrote to say that she was with child—Tobias King’s child—but there were some complications, and would I mind terribly much to move down until the baby’s birth?

Now Tobias finishes reading from the Psalms, closes the heavy Bible, and bows his head. The community follows suit. For five whole minutes not a word is spoken, but each of us is supposed to remain in a state of silent prayer. I want to pray, but I find even the combined vocabulary of the English and Pennsylvania Dutch languages insufficient for the turbulent emotions I feel. Instead, I just close my

eyes and listen to the wind brushing its fingertips through the autumnal tresses of the trees, to the trilling melody of snow geese migrating south, to the horses stomping in the churchyard, eager to be freed from their cumbersome buggies and returned to the comfort of the stall.

Although Tobias gives us no sign, the community becomes aware that the prayer time is over, and everyone lifts his or her head. The men then harness ropes around Amos’s casket, slide out the boards that were bracing it over the hole, and begin to lower him into his grave.

I cannot account for the tears that form in my eyes as that pine box begins its jerky descent into darkness. I did not know Amos well enough to mourn him, but I did know that he was a good man, a righteous man, who had extended his hand of mercy to me without asking questions. Now that his son has taken over as bishop of Copper Creek, I fear that hand will be retracted, and perhaps the tears are more for myself and my child than they are for the man who has just left this life behind.

AMOS

AMOS