The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (7 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Several classical authors clearly used ‘Celts’ in the nonspecific sense of ‘Western Barbarians’. This lack of clarity about peoples, ethnicity and geography is still common today and should not be used as an excuse to bin all classical descriptions of Celts. Many British today refer to ‘Asians’ when what they mean is ‘people from the Indian subcontinent’, and an apocryphal story of a television quiz has an English girl identifying the language spoken by people in China as ‘Asian’. This kind of loose

usage obviously reflects more on the knowledge of the user than on the specificity of such terms. It cannot be used to invalidate statements by other classical authors, who were more careful with the terms they used. I do not intend to tabulate every word that was written about the ancient Celts. Others have done this at length, both arguing for, and against the Central European Celtic homeland.

21

In reviewing these commentaries, I will focus on those statements by classical authors, which demonstrate specific locators and valid context.

When I rang Simon James with my question about original classical sources for the orthodox view of Celtic origins, he also pointed me at two books written over the past two decades with titles resonant of the world of Obelix and Asterix. These were Barry Cunliffe’s

Greeks, Romans and Barbarians

22

and David Rankin’s

Celts and the Classical World

.

23

As an afterthought, he mentioned John Collis’s recent book, on the sceptical side of the fence.

24

As it happened, I got access to the older ‘orthodox’ books several weeks before I obtained the sceptical one. So I shall start first with my own impressions, gained by perusing their cited evidence and that of Barry Cunliffe’s more recent views as expressed in his book

Facing the Ocean

.

25

In his search for Celtic origins, Rankin quotes from Avenius’ fourth-century

AD

poem

Ora maritima

extensively and, in my view, inconclusively. His stated reason for using this rather late commentary is Avenius’ own claim to have had access to many texts, some very ancient. The most important of these is the

lost text of Himilco’s

Periplus of the Northern Sea

. Himilco was a Punic (Carthaginian) admiral who explored the north-west coast of Europe at the end of the sixth century

BC

. Avenius’ poem gives verifiable information on the Atlantic coasts of Spain and Portugal, mentioning the Pillars of Hercules (Straits of Gibraltar), Cadiz, Tartessus and the Gulf of Oestrimnicus, and the impressive Cordillera Cantabri mountains (ridge of Oestrimnis) towering over its southern shore.

26

At this point, however, Avenius’ account becomes more difficult to follow. According to him, within the Gulf of Oestrimnicus arise the Oestrimnides Islands. Since Avenius describes these islands as rich in the mining of tin and lead and mentions the use of curraghs (leather-covered coracles), Rankin identifies them as either the Cassiterides (the ‘tin islands’ used by the Phoenician traders) or just as Cornwall.

27

According to modern interpretation of other sources,

28

‘Cassiterides’ is thought to refer, misleadingly, both to Cornwall and to the north-west coast of Spain, neither of which are islands in their own right. Avenius says that Tartessus traded with the Oestrimnides, which would certainly fit the archaeology of the long-term trade between the Cadiz (then known as Gadir) area and north-west Spain.

29

One might even add the peninsula of Brittany, also a source of tin, to the ‘peninsular’ tin islands of the Cassiterides. The tip of the Breton Peninsula is nearer to that of Cornwall (Land’s End) than it is to any other part of France outside Brittany. The lack of any reference by Avenius to the English Channel highlights this key geographical feature, which through the ages determined and directed the Atlantic coastal trade route from Spain and southern France and then along the western fringes of the British Isles (

Figure 1.2

).

30

Cornwall would make sense as one of the Oestrimnides, because Avenius goes on to say that it is two days’ sailing from there to the Sacred Isle (Ireland), inhabited by the race of Hiberni, with the island of the Albions (Britain) nearby. Finally getting to Celts – the ultimate point of the quote – Avenius’ report of Himilco’s sea voyage takes us further north. Since the preceding leg of his voyage brought Himilco to the Irish Sea, this next section of his port-by-port

periplus

(literally his captain’s log) presumably sees him moving north through the Irish Sea to the west coast of Scotland:

… away from the Oestrimnides

under the pole of Lycaon (in the Northern sky)

where the air is freezing, he comes to the Ligurian land, deserted

by its people: for it has been emptied by the power of the Celts

a long time since in many battles. The Ligurians, displaced, as fate often

does to people, have come to these regions. Here they hold on in rough country

with frequent thickets and harsh cliffs, where mountains threaten the sky.

31

The wild, freezing, mountainous country would certainly fit Scotland. If so, it would be the only classical reference that directly links Celts with the British Isles – a tantalizing anomaly.

Even more anomalous, however, is the confusing reference to some former inhabitants in this northern wasteland who were chased out by the Celts. Himilco called these unfortunates the Ligurians. Avenius goes on to say that the Ligurians had at first hidden themselves in the interior of this northern land before gaining sufficient courage to migrate south to Ophiussa (Portugal) and then to the Mediterranean and Sardinia. The reason that these lines of the

Ora maritima

are all so odd is that numerous classical references place Ligurians ‘at home’ in the Italian and French Riviera, and there is no other mention of a homeland near Scotland. Indeed, the Italian Riviera is today called Liguria, and has a distinct Franco-Italic dialect known as Ligurian. Several authors, includ ing those cited by Avenius, relate that Celts and Ligurians jostled with the Greek Marseillaise for space in this region in the first millennium

BC

.

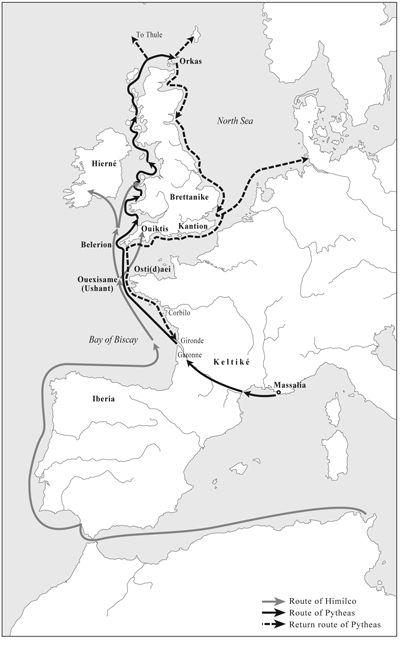

Figure 1.2

Early voyagers up the Atlantic Coast: Pytheas and Himilco. Pytheas the Greek bypassed Spain to get to Britain in the late fourth century

BC

. He may have reached as far north as Shetland. Himilco, a Carthaginian admiral, is reputed to have sailed to the British Isles two hundred years before – via Cadiz.

The simplest explanation is that Avenius, ignorant of the geographical location of Liguria, had performed a mistaken scissors-and-paste job on his many ancient source texts and confused the Riviera with Scotland. This does not wash. Given his post as Roman Proconsul of North Africa towards the end of the Roman Empire, and the kudos he hoped to gain by his literary effort, it is highly unlikely that he was ignorant of Liguria on the Riviera over the other side of the Mediterranean. He may, however, have known something we do not about the origins of the Ligurians and their connections with Celts, and the British Isles, not to mention Himilco’s throwaway remarks about Ligurians travelling south via Portugal and Sardinia – both locations on the Phoenician trade network.

In the context of Phoenicians, the other very remote possibility is that Avenius actually meant people in Scotland similar to Phoenicians i.e. Semitic-speaking. This would fit a theory elaborated by German linguist Theo Vennemann, which argues

among other things, that Picts were a Semitic-speaking remnant of a pre-Celtic people in the British Isles (see p. 251).

Other modern readers of these lines of Avenius have placed Himilco’s northern Ligurians variously in northern Spain or the Baltic coast. I think that the best approach is to accept the most parsimonious text analysis, which is that Himilco thought there were Celts and some other people in Scotland, but to be sceptical about the reference. So we are left with this mysterious suggestion of migrational links up and down the Atlantic coast.

So much for Avenius, who, whatever else he wrote, gave no comfort to the concept of a Central European Celtic homeland. Rather, he raises the possibility of an Atlantic coastal connection. A major problem in trying to untangle such later Roman accounts is their recurrent references to the same earlier Greek sources, many of which are now lost.

There was another early explorer whose trip to the British Isles may partially validate or even replace some of Avenius’ geographical claims. This was the explorer Pytheas, of the Greek colony of Marseilles, whose account of his own 330

BC

odyssey is unfortunately lost. Instead, his text comes to us in fragments, reproduced with venomous incredulity as asides in Strabo’s

Geography

, which was written in Greek around

AD

20. Strabo repeats Pytheas’ names of Atlantic coastal promontories, in particular Cabaeum (Brittany), with a people called the Ostimioi, and their offshore islands,

32

the outermost of which was called Uxisame (today’s Île de Ouessant, or Ushant, off the tip of Brittany). Strabo states that these were all part of Celtica, rather than Iberia. The similarity of geography and names has

been used to link Himilco’s Oestrimnis and Oestrimnides with the Ostimioi and thus, at least partly, with Brittany, but does not clear up the confusion of identity between the Spanish and Breton sources of tin on either side of the huge Bay of Biscay.

33

North of Brittany, Pytheas the Greek seems to have taken much the same route as Himilco the Punic admiral, moving via Cornwall to the Irish Sea and even beyond Scotland, to Shetland and Orkney. Other accounts confirm and fill out the role of Cornwall.

34

As an expert on the archaeology of the Atlantic coast, Barry Cunliffe has drawn some of these and other fragments and strands together with the more solid cultural and archaeological evidence. He makes a geographic reconstruction of the mid-first millennium

BC

tin trade between the producers on the Atlantic coast (the Atabri/Cantabri of north-coast Spain, the Cornish and the Bretons) and the middlemen in southern France and Spain and the rest of the north-west Mediterranean coast. His reconstruction identifies two separate rival networks (

Figure 1.2

).

35

The Punic/Phoenician state consortium to which Himilco belonged ran the southern and older of these two networks. The locations of Punic pottery suggest that it stretched mainly from Cadiz, north along the coast just as far as north-west Spain. Since this western Mediterranean consortium also controlled the Straits of Gibraltar, the rest of the Mediterranean traders – in particular the Greeks – were prevented from using this gateway to the tin-producers.

So instead, the Marseilles Greeks seem to have used their connections with the people of ‘Keltiké’ (as Pytheas called southern France, according to Strabo) around Marseilles and

Narbonne, who most likely used an alternative cross-country route just north of the Pyrenees to gain access to the Atlantic coast from the Mediterranean, thus bypassing Gibraltar (

Figure 1.2

). This may seem quite a trek, but there are good waterways most of the way across, starting from Narbonne, moving up the river Aude and through the Carcassone gap to Toulouse, and then down the river Garonne to Bordeaux and the Gironde on the Atlantic coast. Cunliffe neatly resolves some of the reasons for Strabo’s disbelief at Pytheas’ travel times by using his own text to suggest that Pytheas, as a Greek pioneer, actually took this trade route across Keltiké. By his discoveries further north, Pytheas could have opened up an opportunity for the rest of the Mediterranean to bypass the Punic/Phoenician Atlantic coastal monopoly in their search for tin (

Figure 1.2

).

36