The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (13 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Bede refers to Pictish in his

Ecclesiastical History

(

AD

731). Bede lived in Jarrow in the north of England at a time when Pictish was still being spoken in Scotland. His first-hand observation should, hopefully, be more useful than his historical compilations of Gildas, who was much more concerned about religion than accuracy. Twice, Bede clearly indicates that there were four indigenous languages spoken in Britain: Gaelic, British (i.e. ‘Brythonic’), English and Pictish. He describes Picts as invaders who arrived windswept in Northern Ireland in longboats from Scythia. Not being allowed to settle there, they made their home in Scotland.

36

How they reached the British Isles from Scythia, east of the Mediterranean, Bede does not make clear, but elsewhere in Medieval literature the region of Scythia is sometimes alluded to as the ultimate Norse homeland in the Danish and Icelandic sagas.

37

The longboats might imply the Picts were from Scandinavia (see

Chapter 10

), but in any case

this story from Bede makes it clear that he did not think that they were either British or Irish. His linguistic skill should have been enough to work this one out for himself.

38

Bede also refers to the Pictish name for modern Kinneil at one end of the Antonine Wall (a Roman fortified defence, stretching between Edinburgh and Glasgow, north of Hadrian’s Wall) as Peanfahel. While this appears to support the view that Pictish was not the same as Gaelic, it would leave a puzzle. In a Brythonic language (also known as

P-celtic

– see p. 88),

pean

or

penn

might mean ‘end’, but the second half of the name, -

fahel

, would appear to be Gaelic, meaning ‘[of] wall’. A name meaning ‘end of wall’ is appropriate for the location, but the word would be a compound mixture of Gaelic and some P-celtic language. Kenneth Jackson points out that such compounds are no rarity, and gives the etymology for some other words and place-names that support the presence of a P-celtic language north-east of Edinburgh. He argues that this was ‘a Gallo-Brittonic dialect not identical with the British spoken south of the Antonine Wall, different from the British-P-celtic used south of the Antonine Wall, although related to it’. According to the place-name evidence, this ‘P’-celtic language would have been distributed in Scotland north-east of Edinburgh and the Forth river.

39

This distribution coincides with the main Scottish concentration of celtic-inscribed stones on the east coast (

Figures 2.2

and

7.4

).

However, Jackson argued, from the evidence of Ogham inscriptions (Ogham being an alphabetic script used throughout insular-celtic-speaking areas often with celtic–Latin bilingual inscriptions in the fifth century and onwards), that there was a third language in northern Scotland apart from Scottish Gaelic and the P-celtic language: ‘The other was not Celtic at all,

which would fit the relative absence of celtic place-names in northern Scotland, nor apparently even Indo-European, but was presumably the language of some very early set of inhabitants of Scotland’ (

Figure 2.1b

).

40

Jackson’s concept of a third language is now viewed by some as a minority view, but Colin Renfrew in his book

Archaeology and Language

chooses to take it seriously, referring to Jackson as having been ‘the leading living authority’.

41

German linguist Theo Vennemann has recently suggested on place-name and other evidence that this non-Indo-European Pictish language could have been derived from Semitic as a result of Neolithic intrusions of forebears of the Phoenicians (see p. 250).

This would leave ancient northern Scotland with three distinct languages, one of which was spoken to the west and two to the east of the Grampians for a large part of the first millennium

AD

. However, the western language, Scottish Gaelic, which apparently displaced the other two, is regarded as an intruder during that period. What is odd about the disappearance of Pictish is that the Picts were in the ascendant during the Dark Ages, according to both Gildas and Bede. Their attacks on England were stated by Gildas as being part of the reason for inviting the Saxons, so why should both their putative languages have disappeared so comprehensively, when Gaelic was essentially the dominant language of the Argyll west of the Grampians? I shall come back to this puzzle again in the second part of the book.

The generally accepted view is that Scottish Gaelic was derived not from Scotland, or Caledonia as the Romans called it, but from Irish Gaelic, from the Irish tribe previously called the

Scotti by the Romans. This may come as a surprise to some readers, but is generally felt to be incontestable. It seems that not even the name ‘Scot’ belongs in Scotland.

But – find an incontestable position, and there will be sure to be someone to oppose it. In an appropriately titled article ‘Were the Scots Irish?’ in the august archaeological journal

Antiquity

, Scottish archaeologist Ewan Campbell, of the University of Glasgow, recently did just that. He starts his polemic by outlining the conventional story of how

the Scots founded the early kingdom of

Dál Riata

in western Scotland in the early sixth century, having migrated there from north-eastern Antrim, Ireland. In the process they displaced a native Pictish or British people from an area roughly equivalent to the modern county of Argyll. Later, in the mid-ninth century, these Scots of

Dál Riata

took over the kingdom of

Alba

, later to become known as Scotland.

42

Campbell then claims that ‘There had never been any serious archaeological justification for the supposed Scottic migration’, citing a 1970 study which failed to find any archaeological evidence for cultural transplantation, into either Scotland or other parts of western Britain such as Galloway. He then goes through the inconsistencies and gaps in the archaeological and historical evidence.

43

It is Campbell’s analysis of the linguistic evidence that is most likely to raise objections – from linguists. He does acknowledge that the phenomenon of Ogham inscriptions came from Ireland. However, he does not mention Patrick Sims-Williams’ inference from those inscriptions that the Irish Gaelic language and names made significant inroads into Wales over the same period, although their influence subsequently faded.

44

This evidence for an Irish linguistic intrusion during the Dark Ages does not necessarily invalidate Campbell’s main alternative. He suggests that, rather than being limited by the Irish Sea until the first millennium

AD

, Gaelic languages and culture had extended across the North Channel between Antrim and Argyll and Galloway for much longer, perhaps back as far as the Iron Age. A glance at any map of the British Isles shows that geographically, his argument is sound. Ireland, the Isle of Man and western Scotland are very close to one another across the Northern Channel, far closer than the steps on the sea-trading links between northern Spain, Brittany, Cornwall, south-west Wales and County Wexford in Ireland. From the Bronze Age onwards, the sea route would have been far easier for trade than overland, and northern Scotland had the added geolinguistic barrier of the Druim Albin, the ‘Spine of Britain’, the Grampian Highlands.

45

Campbell also argues for Brythonic intrusions in the opposite direction, from Britain into Ireland. He is not alone. Ivernic, for instance, is said to be an extinct Brythonic language that was spoken in Ireland, particularly in the south-west, by a tribe called the

Érainn

(Irish) or

Iverni

(Latin). There are several independent fragments of evidence to support the notion of Brythonic languages having been spoken at some time in some parts of Ireland, either before or after the present insular-celtic Gaelic (or Goidelic) branch became dominant. David Rankin points to Ptolemy’s description of eastern Ireland, which he says mentions four ‘British-sounding and possibly British connected tribes, such as Brigantes’. Rankin suggests that these could have been possible refugees from the Romans in Britain.

46

These ideas of Brythonic speakers in Ireland are also bound up with legendary concepts of multiple pre-Roman invasions of Ireland. Not the least used of the sources is the traditional written Irish (Goidelic) record, in particular the

Lebor Gabála Érenn

,

47

drawing on the oldest traditions of all from the celtic language, which records four invasions. Such traditions record, among others, several presumedly celtic invasions, including Cruithni (Priteni, or Picts) and the Firbolgs (or

Érainn

), who comprised three groups from either Greece or Spain. These invasions are all supposed to have occurred before the final invasion of the Gaelic Milesians, also either from Greece or Spain.

David Rankin has reviewed this controversial argument, presented most strongly by Thomas O’Rahilly in 1946,

48

that there was a pre-Gaelic, Brythonic presence in Ireland. Although Rankin is equivocal, he does feel that the linguistic evidence points towards an agreement with the Irish legends that the last invasion, that of the Goidels or Gaels, was from Spain.

49

However, to make this point Rankin assumes that Gaelic was coeval with prehistoric Spanish-Celtic languages, while Brythonic was coeval with Gaulish in France.

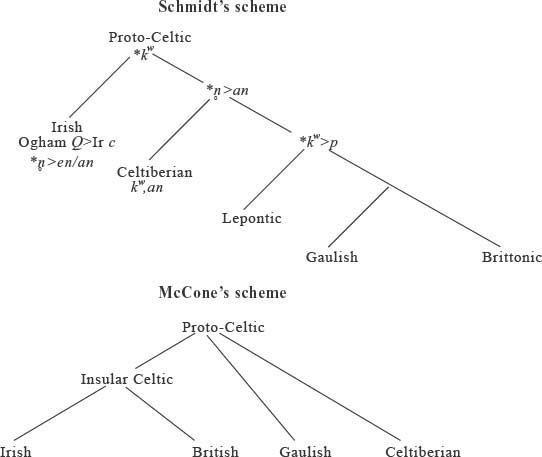

As with people and genes, trees of ancestry can be reconstructed for languages based on the degree of shared characteristics in particular shared innovations or changes. Problems arise when the retention of some characteristics do not match those of others. Rankin’s attractive simplistic division for the ancestry of Welsh celtic from Gaulish in France and Irish celtic from Spain is based on the well-known shared use of a ‘P’ sound in Brythonic languages where Gaelic languages would use a hard ‘Q’ consonant, This division was used, among others, by the linguist Karl Horst Schmidt to construct a controversial formal deep-split language tree with P-celtic – which includes Brythonic, and also Gaulish and Lepontic – on one branch, and Q-celtic – which includes Gaelic and Iberian celtic – on the other. On this basis, Brythonic and Goidelic (i.e. Brittonic and Irish in

Figure 2.4

a) are on opposite sides of the celtic tree, and the Continental celtic languages are scattered in between.

50

The problem is that, as usual, linguists are divided down the middle. In this case, they disagree on the relative importance of the P/Q division. The deep structure of the celtic language tree would be different if P’s and Q’s in celtic just turned out to be a convenient description of Brythonic vs Goidelic, rather than a valid way of dividing the origins of Continental and insular-celtic languages as well.

51

Figure 2.4

Celtic confusion. Schmidt’s (a) and McCone’s (b) alternative trees of insular-celtic provide radically different interpretations of origins from the Continent. In Schmidt’s tree (partly based on the P/Q change), Gaelic (e.g. Irish) links with ancient Celtiberian in Spain, while Brittonic (e.g. Welsh) links with ancient Gaulish in France. In McCone’s version (based more on ‘areal’ similarities), Brittonic and Gaelic are more closely related to each other.

The P- and Q-celtic classification is indeed a useful rule of thumb for dividing Brythonic from Goidelic insular-celtic languages, based on the use, in various shared words, of a

p

sound in Welsh and a hard

c

,

q

,

g

or

k

in Gaelic. A simple example can be seen in Welsh numerals which use

p

in

pedair

and

pump

for ‘four’ and ‘five’ rather than the Gaelic hard

c

in

ceathair

and

cuêig

. Old Gaulish has

petor

/

petvar

and

pempe

/

pinpe

for four and five, which according to this rule would make it P-celtic.

But for some celtic linguists the existence of a consonant change between Brythonic and Goidelic is as far as it goes, and deep celtic-language ‘genetic’ splits based on this linguistically common shift may be unwise. Such P and Q changes have also occurred in other Indo-European languages with q>p being much commoner than p>q. For example, the reconstructed root words for ‘four’ and ‘five’ at the base of the vast Indo-European language tree are

kwetwores

and

penkwe

. Like Goidelic, most Romance languages, including Latin and French, have retained the

k

sound (e.g.

quatuor

,

quatre

) but converted the

p

in

penkwe

to

qu

(e.g.

quinque

,

cinq

). However, two ancient Italic dialects, Umbrian and Oscan, went for

p

in both words, in the same way as in Brythonic. Similarly, most Greek dialects have gone the

p

way, converting the

kw

to

p

or

t

in four but retaining the

p

in five (e.g.

pessares

/

teseres

and

pempe

/

pende

). Greek is only very distantly related to most European languages including

celtic. So, this

p

to

q

consonant change is common in either direction in Indo-European languages, and although it is useful, it cannot be used as a stable marker for deep language splits. In other words, if you watch your P’s and Q’s too closely you may get a Greek grandmother.