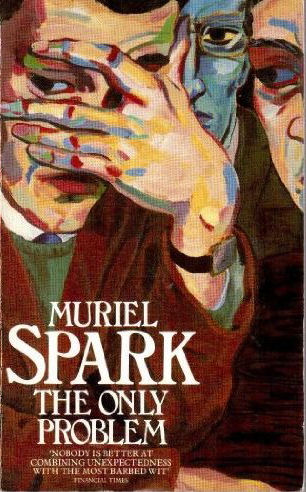

The Only Problem

Authors: Muriel Spark

THE

ONLY PROBLEM

Muriel Spark

Surely I would speak to the Almighty,

and I desire to reason with God.

Book of Job,

13,3.

PART

ONE

ONE

He was driving along the

road in France from St Dié to Nancy in the district of Meurthe; it was straight

and almost white, through thick woods of fir and birch. He came to the grass

track on the right that he was looking for. It wasn’t what he had expected.

Nothing ever is, he thought. Not that Edward Jansen could now recall exactly

what he had expected; he tried, but the image he had formed faded before the

reality like a dream on waking. He pulled off at the track, forked left and

stopped. He would have found it interesting to remember exactly how he had

imagined the little house before he saw it, but that, too, had gone.

He sat

in the car and looked for a while at an old green garden fence and a closed

gate, leading to a piece of overgrown garden. There was no longer a visible

path to the stone house, which was something like a lodgekeeper’s cottage with

loose tiles and dark, neglected windows. Two shacks of crumbling wood stood

apart from the house. A wider path, on Edward’s side of the gate, presumably

led to the château where he had no present interest. But he noticed that the

car-tracks on the path were overgrown, very infrequently used, and yet the

grass that spread over that path was greener than on the ground before him,

inside the gate. If his wife had been there he would have pointed this out to

her as a feature of Harvey Gotham, the man he had come to see; for he had a

theory, too unsubstantiated to be formulated in public, but which he could

share with Ruth, that people have an effect on the natural greenery around them

regardless of whether they lay hands on it or not; some people, he would

remark, induce fertility in their environment and some the desert, simply by

psychic force. Ruth would agree with him at least in this case, for she didn’t

seem to like Harvey, try as she might. It had already got to the point that

everything Harvey did and said, if it was only good night, to her mind made him

worse and worse. It was true there are ways and ways of saying good night. Yet

Edward wondered if there wasn’t something of demonology in those confidences he

shared with Ruth about Harvey; Ruth didn’t know him as well as Edward did. They

had certainly built up a case against Harvey between themselves which they

wouldn’t have aired openly. It was for this reason that Edward had thought it

fair that he should come alone, although at first he expected Ruth to come with

him. She had said she couldn’t face it. Perhaps, Edward had thought, I might be

more fair to Harvey.

And

yet, here he was, sitting in the car before his house, noting how the grass

everywhere else was greener than that immediately surrounding the cottage.

Edward got out and slammed the door with a bang, hoping to provoke the dark

front door of the house or at least one of the windows into action. He went to

the gate. It was closed with a rusty wire loop which he loosened. He creaked open

the gate and walked up the path to the door and knocked. It was ten past three,

and Harvey was expecting him; it had all been arranged. But he knocked and

there was silence. This, too, was typical. He walked round the back of the

house, looking for a car or a motor-cycle, which he supposed Harvey had. He

found there a wide path, a sort of drive which led away from the back door,

through the woods; this path had been hidden from the main road. There was no

motor-cycle, but a newish small Renault, light brown, under a rush-covered

shelter. Harvey, then, was probably at home. The back door was his front door,

so Edward banged on that. Harvey opened it immediately and stood with that look

of his, to the effect that he had done his utmost.

‘You

haven’t cut your hair,’ he said.

Edward

had the answer ready, heated-up from the pre-cooking, so many times had he told

Harvey much the same thing. ‘It’s my hair, not your hair. It’s my beard, not

your beard.’ Edward stepped into the house as he said this, so that Harvey had

to make way for him.

Harvey

was predictable only up to a point. ‘What are you trying to prove, Edward,’ he

said, ‘wearing that poncho at your age?’ In the living room he pushed some

chairs out of the way. ‘And your hair hanging down your back,’ he said.

Edward’s

hair was in fact shoulder-length. ‘I’m growing it for a part in a film,’ he

said then wished he hadn’t given any excuse at all since anyway it was his

hair, not Harvey’s hair. Red hair.

‘You’ve

got a part?’

‘Yes.’

‘What

are you doing here, then? Why aren’t you rehearsing?’

‘Rehearsals

start on Monday.’

‘Where?’

‘Elstree.’

‘Elstree.’

Harvey said it as if there was a third party listening — as if to draw the

attention of this third party to that definite word, Elstree, and whatever

connotations it might breed.

Edward

wished himself back in time by twenty minutes, driving along the country road

from St Dié to Nancy, feeling the spring weather. The spring weather, the

cherry trees in flower, and all the budding green on the road from St Dié had

supported him, while here inside Harvey’s room there was no outward support. He

almost said, ‘What am I doing here?’ but refrained because that would be mere

rhetoric. He had come about his sister-in-law Effie, Harvey’s wife.

‘Your

wire was too long,’ said Harvey. ‘You could have saved five words.’

‘I can

see you’re busy,’ said Edward.

Effie was very far from

Edward’s heart of hearts, but Ruth worried about her. Long ago he’d had an

affair with beautiful Effie, but that was a thing of the past. He had come here

for Ruth’s sake. He reminded himself carefully that he would do almost anything

for Ruth.

‘What’s

the act?’ said Harvey. ‘You are somehow not yourself, Edward.’

It

seemed to Edward that Harvey always suspected him of putting on an act.

‘Maybe

I can speak for actors in general; that, I don’t know,’ Edward said. ‘But I

suppose that the nature of my profession is mirrored in my own experience; at

least, for certain, I can speak for myself. That, I can most certainly do. In

fact I know when I’m playing a part and when I’m not. It isn’t every actor who

knows the difference. The majority act better off stage than on.’

Edward

went into the little sitting room that Harvey had put together, the minimum of

stuff to keep him going while he did the job he had set himself. Indeed, the

shabby, green plush chairs with the stuffing coming out of them and the quite

small work-table with the papers and writing materials piled on it (he wrote by

hand) seemed out of all proportion to the project. Harvey was only studying a

subject, preparing an essay, a thesis. Why all this spectacular neglect of

material things? God knows, thought Edward, from where he has collected his

furniture. There was a kitchen visible beyond the room, with a loaf of bread

and a coffee mug on the table. It looked like a nineteenth century narrative

painting. Edward supposed there were habitable rooms upstairs. He sat down when

Harvey told him to. From where he sat he could see through a window a

washing-line with baby clothes on it. There was no sign of a baby in the house,

so Edward presumed this washing had nothing to do with Harvey; maybe it

belonged to a daily help who brought along her child’s clothes to wash.

Harvey

said, ‘I’m awfully busy.’

‘I’ve

come about Effie,’ Edward said.

Harvey

took a long time to respond. This, thought Edward, is a habit of his when he

wants an effect of weightiness.

Then, ‘Oh,

Effie,’

said Harvey, looking suddenly relieved; he actually began to

smile as if to say he had feared to be confronted with some problem that really

counted.

Harvey had written Effie

off that time on the Italian

autostrada

about a year ago, when they were

driving from Bologna to Florence — Ruth, Edward, Effie, Harvey and Nathan, a

young student-friend of Ruth’s. They stopped for a refill of petrol; Effie and

Ruth went off to the Ladies’, then they came back to the car where it was still

waiting in line. It was a cool, late afternoon in April, rather cloudy, not one

of those hot Italian days where you feel you must have a cold drink or an ice

every time you stop. It was sheer consumerism that made Harvey — or maybe it

was Nathan — suggest that they should go and get something from the snack-bar;

this was a big catering monopoly with huge windows in which were arranged straw

baskets and pottery from Hong Kong and fantastically shaped bottles of Italian

liqueurs. It was, ‘What shall we have from the bar?’ — ‘A sandwich, a coffee?’

—’No, I don’t want any more of those lousy sandwiches.’ Effie went off to see

what there was to buy, and came back with some chocolate. —

‘Yes,

that’s what I’d like.’ — She had two large bars. The tank was now full. Edward

paid the man at the pump. Effie got in the front with him. They were all in the

car and Edward drove off. Effie started dividing the chocolate and handing it

round. Nathan, Ruth and Harvey at the back, all took a piece. Edward took a

piece and Effie started eating her piece.

With

her mouth full of chocolate she turned and said to Harvey at the back, ‘It’s

good, isn’t it? I stole it. Have another piece.’

‘You

what?’ said Harvey. Ruth said something, too, to the same effect. Edward said

he didn’t believe it.

Effie

said, ‘Why shouldn’t we help ourselves? These multinationals and monopolies are

capitalising on us, and two-thirds of the world is suffering.’

She

tore open the second slab, crammed more chocolate angrily into her mouth, and,

with her mouth gluttonously full of stolen chocolate, went on raving about how

two-thirds of the world was starving.

‘You

make it worse for them and worse for all of us if you steal,’ Edward said.

‘That’s

right,’ said Ruth, ‘it really does make it worse for everyone. Besides, it’s

dishonest.’

‘Well,

I don’t know,’ Nathan said.

But

Harvey didn’t wait to hear more. ‘Pull in at the side,’ he said. They were

going at a hundred kilometres an hour, but he had his hand on the back door on

the dangerous side of the road. Edward pulled in. He forgot, now, how it was

that they reasoned Harvey out of leaving the car there on the

autostrada;

however,

he sat in silence while Effie ate her chocolate inveighing, meanwhile, against

the capitalist system. None of the others would accept any more of the

chocolate. Just before the next exit Harvey said, ‘Pull in here, I want to pee.

They waited for him while he went to the men’s lavatory. Edward was suspicious

all along that he wouldn’t come back and when the minutes went by he got out of

the car to have a look, and was just in time to see Harvey get up into a truck

beside the driver; away he went.

They

lost the truck at some point along the road, after they reached Florence.

Harvey’s disappearance ruined Effie’s holiday. She was furious, and went on

against him so much that Ruth made that always infuriating point: ‘If he’s so

bad, why are you angry with him for leaving you?’ The rest of them were upset

and uneasy for a day or two but after that they let it go. After all, they were

on holiday. Edward refused to discuss the subject for the next two weeks; they

were travelling along the Tuscan coast stopping here and there. It would have

been a glorious trip but for Effie’s fury and unhappiness.

Up to

the time Edward went to see Harvey in France on her behalf, she still hadn’t

seen any more of him. They had no children and he had simply left her life,

with all his possessions and the electricity bills and other clutter of married

living on her hands. All over a bit of chocolate. And yet, no.