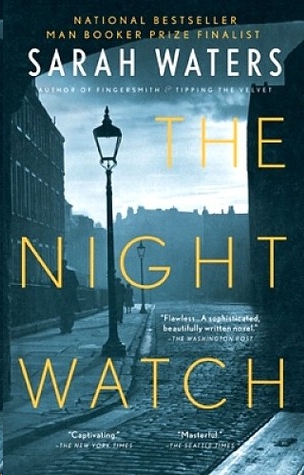

The Night Watch

Authors: Sarah Waters

Tags: #General, #Historical, #1939-1945, #England, #London (England), #Fiction, #World War, #War & Military, #Romance, #london, #Great Britain, #Azizex666@TPB

Sarah Waters

The Night Watch

Sarah Waters

Sarah Waters’ fourth novel, The Night Watch, is set in 1940s London, during and after the Second World War, and is an innovative departure from her previous three lesbian Victorian historical fictions. Tipping the Velvet (1998), Affinity (1999) and Fingersmith (2002) depend on melodramatic scenes of excess and chicanery, with occasional references to postmodern thinking. In comparison, The Night Watch is more constrained in its telling of love stories and secrets. Its tone echoes the view we have, in the 21st century, of rationed wartime Britain and the use of the more distant third-person, rather than the confiding first-person, signals a further diversion from the earlier works.

The structure of The Night Watch is worth remarking upon as it begins at the end in 1947. The second section takes us back to 1944, and the third and final section is set in 1941. The decision to use this type of structure is brave, even foolhardy, because of the problems in pulling it off convincingly, but Waters’ subtlety and restraint in pulling back the layers reveals the extent of her authorial control.

This novel is essentially concerned with five main characters (Kay, Viv, Helen, Julia and Viv’s brother, Duncan) and their separate private lives. The connections between these people are also elemental to the narrative. Coincidence plays a significant role in the unfolding of past events as their lives are shown to overlap. This use of coincidence has been a feature of Waters’ previous novels, but this time she uses it casually, and as an extra element, rather than for the purposes of manipulating the plot out of hand as was deemed necessary in a melodrama such as Fingersmith.

The love stories of Kay, Viv and Helen are central and, as the narrative traces back to 1941, we learn how their present views of relationships have been shaped by these past events. As with her previous novels, Waters continues to use lesbian relationships as a main focus of the narrative, but shifts away to examine the affair between Viv and Reggie, and the horrific illegal abortion she undergoes to spare her father from further shame.

Repression becomes a touchstone as many of the characters keep a secret or carry a weight of shame. The converse of this theme of fear of discovery is the examination of bravery. This is most notable in the second and third sections which are, necessarily, concerned with the bombing of London. A re-evaluation of the definition of courage is undertaken and is perhaps most poignant in the prison scene, where Duncan ’s cell mate, conscientious objector Fraser, asks himself if he is ‘simply a – a bloody coward’ when he is overwhelmed by the fear of death. The deconstruction of received morality, of what is to be brave or selfish in this time of heightened emotions, is also examined when Helen considers the effect the war has had on her ethics: ‘In the first blitz, she’d tried to help everyone; she’d given money to people, sometimes, from her own purse. But the war made you careless. You started off, she thought sadly, imagining you’d be a kind of heroine. You end up thinking only of yourself.’

The reason for Duncan ’s imprisonment is one of the well-kept secrets of the novel and is only (partially) explained in the third section. This use of the hidden truth and the hints at the unspoken strengthen the evocation of the period, where loose lips could potentially sink ships, and walls had ears. When revelations are made, they are, more often than not, as subdued as the repressed tone permits and this allows the novel to maintain the same pace throughout.

Despite this steady pace, Waters still enables the readers to see how the war also had a liberating effect on women such as Kay. Her gallantry and masculine demeanour was of use during the bombings whilst she worked as an ambulance driver, but in the beginning of the novel, in 1947, it is clear that with the return to peace time her short hair and male clothing are once more worthy of ridicule.

As with all of Waters’ novels, The Night Watch has been praised by critics for the attention to detail and meticulous research. This work stretches beyond the limits of the previous three, though, and is certainly her most impressive to date. Her control in depicting the central characters gradually is in itself an indicator of skilful writing. As this is also combined with a believable and interested evocation of period and place, this novel must be recommended highly.

To Lucy Vaughan

1947

1

So this, said Kay to herself, is the sort of person you've become: a person whose clocks and wristwatches have stopped, and who tells the time, instead, by the particular kind of cripple arriving at her landlord's door.

For she was standing at her open window, in a collarless shirt and a pair of greyish underpants, smoking a cigarette and watching the coming and going of Mr Leonard's patients. Punctually, they came-so punctually, she really could tell the time by them: the woman with the crooked back, on Mondays at ten; the wounded soldier, on Thursdays at eleven. On Tuesdays at one an elderly man came, with a fey-looking boy to help him: Kay enjoyed watching for them. She liked to see them making their slow way up the street: the man neat and dark-suited as an undertaker, the boy patient, serious, handsome-like an allegory of youth and age, she thought, as done by Stanley Spencer or some finicky modern painter like that. After them there came a woman with her son, a little lame boy in spectacles; after that, an elderly Indian lady with rheumatics. The little lame boy would sometimes stand scuffing up moss and dirt from the broken path to the house with his great boot, while his mother spoke with Mr Leonard in the hall. Once, recently, he'd looked up and seen Kay watching; and she'd heard him making a fuss on the stairs, then, about going on his own to the lavatory.

'Is it them angels on the door?' she had heard his mother say. 'Good heavens, they're only pictures! A great boy like you!'

Kay guessed it wasn't Mr Leonard's lurid Edwardian angels that frightened him, but the thought of encountering her. He must have supposed she haunted the attic floor like a ghost or a lunatic.

He was right, in a way. For sometimes she walked restlessly about, just as lunatics were said to. And other times she'd sit still, for hours at a time-stiller than a shadow, because she'd watch the shadows creeping across the rug. And then it seemed to her that she really might be a ghost, that she might be becoming part of faded fabric of the house, dissolving into the gloom which gathered, like dust, in its crazy angles.

A train ran by, two streets away, heading into Clapham Junction; she felt the thrill and shudder of it in the sill beneath her arms. The bulb in a lamp behind her shoulder sprang into life, flickered for a second like an irritated eye, and then went out. The clinker in the fireplace-a brutal little fireplace; this had been a room for a servant, once-gently collapsed. Kay took a final draw on her cigarette, then pinched out the flame of it between her forefinger and thumb.

She had been standing at her window for more than an hour. It was a Tuesday: she'd seen a snub-nosed man with a wasted arm arrive, and had been waiting, in a vague kind of way, for the Stanley Spencer couple. But now she'd decided to give up on them. She'd decided to go out. The day was fine, after all: a day in the middle of a warm September, the third September after the war. She went through to the room, next to this one, that she used as a bedroom, and began to get changed.

The room was dim. Some of the window-glass had been lost, and Mr Leonard had replaced it with lino. The bed was high, with a balding candlewick bedspread: the sort of bed which turned your thoughts, not pleasantly, to the many people who must, over the years, have slept on it, made love on it, been born on it, died on it, thrashed around on it in fevers. It gave off a slightly sour scent, like the feet of worn stockings. But Kay was used to that, and didn't notice. The room was nothing to her but a place in which to sleep or to lie sleepless. The walls were empty, featureless, just as they had been when she'd moved in. She'd never hung up a picture or put out books; she had no pictures or books; she didn't have much of anything. Only, in one of the corners, had she fixed up a length of wire; and on this, on wooden hangers, she kept her clothes.

The clothes, at least, were very neat. She picked her way through them now and found a pair of nicely-darned socks, and some tailored slacks. She changed her shirt to a cleaner one, a shirt with a soft white collar she could leave open at the throat, like a woman might.

But her shoes were men's shoes; she spent a minute polishing them up. And she put silver links in her cuffs, then combed her short brown hair with brushes, making it neat with a touch of grease. People seeing her pass in the street, not looking at her closely, often mistook her for a good-looking youth. She was regularly called 'young man', and even 'son', by elderly ladies. But if anyone gazed properly into her face, they saw at once the marks of age there, saw the white threads in her hair; and in fact she would be thirty-seven on her next birthday.

When she went downstairs she stepped as she carefully as she could, so as not to disturb Mr Leonard; but it was hard to be soft-footed, because of the creaking and popping of the stairs. She went to the lavatory, then spent a couple of minutes in the bathroom, washing her face, brushing her teeth. Her face was lit up rather greenishly, because ivy smothered the window. The water knocked and spluttered in the pipes. The gesyer had a spanner hanging beside it, for sometimes the water stuck completely-and then you had to bang the pipes about a bit to make it fire.

The room beside the bathroom was Mr Leonard's treatment-room, and Kay could hear, above the sound of the toothbrush in her own mouth and the splash of water in the basin, his passionate monotone, as he worked on the snub-nosed man with the wasted arm. When she let herself out of the bathroom and went softly past his door, the monotone grew louder. It was like the throb of some machine.

'Eric,' she caught, 'you must

hmm-hmm

. How can

buzz-buzz

when

hmm-buzz

whole again?'

She stepped very stealthily down the stairs, opened the unlatched front door, and stood for a moment on the step-almost hesitating, now. The whiteness of the sky made her blink. The day seemed limp, suddenly: not fine so much as dried out, exhausted. She thought she could feel dust, settling already on her lips, her lashes, in the corners of her eyes… But she wouldn't turn back. She had, as it were, her own brushed hair to live up to; her polished shoes, her cufflinks. She went down the steps and started to walk. She stepped like a person who knew exactly where they were going, and why they were going there-though the fact was, she had nothing to do, and no-one to visit, no-one to see. Her day was a blank, like all of her days. She might have been inventing the ground she walked on, laboriously, with every step.

She headed west, through well-swept, devastated streets, towards Wandsworth.

'No sign of Colonel Barker today, Uncle Horace,' said Duncan, looking up at the attic windows as he and Mr Mundy drew closer to the house.

He was rather sorry. He liked to see Mr Leonard's lodger. He liked the bold cut of her hair, her mannish clothes, her sharp, distinguished-looking profile. He thought she might once have been a lady pilot, a sergeant in the WAAF, something like that: one of those women, in other words, who'd charged about so happily during the war, and then got left over. 'Colonel Barker' was Mr Mundy's name for her. He liked to see her standing there, too. At Duncan 's words he looked up, and nodded; but then he put down his head again and moved on, too out of breath to speak.

He and Duncan had come all the way to Lavender Hill from White City. They had to come slowly, getting buses, stopping to rest; it took almost the whole day to get here and home again afterwards. Duncan had Tuesday as his regular day off, and made the hours up on a Saturday. They were very good about it, at the factory where he worked. 'That boy's devoted to his uncle!' he'd heard them say, many times. They didn't know that Mr Mundy wasn't actually his uncle. They had no idea what kind of treatment he received from Mr Leonard; probably they thought he went to a hospital. Duncan let them think what they liked.

He led Mr Mundy into the shadow of the crooked house. The house always looked at its most alarming, he thought, when looming over you like this. For it was the last surviving building in what had once, before the war, been a long terrace; it still had the scars, on either side, where it had been attached to its neighbours, the zig-zag of phantom staircases and the dints of absent hearths. What held it up, Duncan couldn't imagine; he'd never quite been able to shake off the feeling, as he let himself and Mr Mundy into the hall, that he'd one day close the door a shade too hard and the whole place would come tumbling down around them.