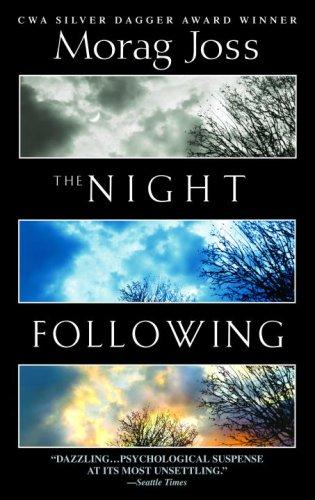

The Night Following

Read The Night Following Online

Authors: Morag Joss

Tags: #Psychological, #Murder, #Psychological Fiction, #Murder Victims' Families, #Married people, #General, #Romance, #Loss (Psychology), #Suspense, #Crime, #Deception, #Fiction, #Murderers

On a blustery April day, the wife of a doctor discovers that her husband has been having an affair. Moments later, driving along a country road, she fails to see sixty-one-year-old Ruth Mitchell up ahead, riding her bicycle. She hits her, killing her instantly, and drives away.

Horrified by what she has done, the doctor’s wife begin to unravel. She turns her attention to Ruth’s bereaved husband, a man staggering through each night, as unhinged by grief as she herself is by guilt.

At first Arthur Mitchell does not realize that someone has begun watching him through his windows, worrying over his disheveled appearance, his increasingly chaotic home. And when at last she steps over through his doorway and insinuates herself into his life, he is ready to believe that, for reasons beyond his understanding, his wife has returned to him

A Novel by

Morag Joss

Morag Joss

by Morag Joss

PATRICK

I am immensely grateful to Kate Burke Miciak at Random House for her clear, generous, and insightful editorship, which has enabled me to produce a better novel than the version she first read. She is that rare gift to any writer, an editor who is exacting and inspiring in equal measure. I thank her for her unending care of and belief in

The Night Following,

which have done more than she may realize to sustain me through some dark periods when writing was a struggle.

I am indebted also to my two wonderful agents, Maggie Phillips at Ed Victor Limited in London and Jean Naggar of the Jean V. Naggar Literary Agency in New York. They are so much more than agents; I appreciate deeply their warmth, kindliness, optimism, and faith.

Permission to use the

Mimosa

poem, written by Maria G. Bracchi-Cambini and dedicated to her daughter Joan, was very kindly given by the late Joan’s brother Bert and her daughters Sue, Anne, and Carol. Thank you.

Finally, I wish to thank my friends and my daughter Hannah, who in their various adorable ways kept me going during the writing of this novel.

I live in a world I have not created

inward or outward. There is a sweetness

in willing surrender: I trail my ideas

behind great truths. My ideas are like shadows

and sometimes I consider how it would have been

to create a credo, objects, ideas

and then to live with them. I can understand

when tides most tug and the moon is remote

and the trapped wild beast is one with its shadow,

how even great faith leaves room for abysses

and the taut mind turns to its own wanderings.

Elizabeth Jennings

(from

Relationships,

published by Macmillan)

Something tells me it’s important not to look dangerous. You would think I’d be beyond it by this time, the old dread of making scenes, but I do want to get it done quietly, with the niceties observed. With some respect for finer feelings, though whose exactly it’s hard to say at this point. If I could be sure of that, if I could be sure they’d take me with an attitude of courteous regret, of sorrow even, that reflects my own, I’d do it today. I would.

My hair and shoes are a little unfortunate but I could make myself tidy. I could practice the proper face in a mirror first. There’s not much I can do about the bones around my eyes that have a bluish, knuckly look about them now, but I think I could upturn my face so it resembled the mask expected of reasonable women entering this supposedly balanced and amiable chapter of middle age. I could clear my throat and imitate the rounded, sprightly cadences of such women’s voices and say—what?

Suppose for instance I said, in that singing-out manner, Oh, excuse me! Could you help? I’m afraid something has happened.

As if I’d dropped a jar at the checkout. Would that be the correct thing?

There must be a right way and a wrong way, as there is for everything. I believe turning up at a police station might be customary, insofar as my particular circumstances are customary. But police stations aren’t in obvious places anymore and I could waste all day looking for one. Or I could dial 999, although call boxes aren’t in obvious places anymore, either. And they would ask me what’s happened because how else are they to know who to send—police, ambulance, or fire engine—and I couldn’t begin to go into it all on the telephone. But what is the emergency, they’ll insist. All I could tell them is that I think I am. I may be the emergency. It’s true that I would be emerging. I would be appearing unexpectedly after a spell of concealment. Surely I must be the emergency. What else could I say? That there’s been an accident?

Once they saw I wasn’t dangerous, I suppose for a time at least they’d prefer to think of me as sick. Indeed, I could just walk into a hospital. That worked before, after a fashion. I could just walk into a hospital, and nobody would ask if I actually believed I could ever find help there for what afflicts me.

The truth is I’m neither sick nor dangerous. I’m merely displaced. Not that that makes me unique. You’ve seen me, or someone like me, anywhere out of the way and out of season, run-down, closing down and in decline, though I may have escaped notice unless you happened to catch me in a small space between thoughts of your own. You will have seen me in odd, deserted places: a woman alone on a bridge, or standing by the roadside at a strange and hazardous point where weeds are sprouting, perhaps just loitering near an inexplicably derelict bus stop. I’ll remind you of loneliness or old age, or that winter’s setting in.

But most often I’ll be in restless places, the passing points of departure and arrival between various somewheres. I’m the one apart and hesitant in the waiting rooms of stations, under the arc lights of ticket halls and in the corner booths, hovering at turnstiles and gates, never quite joining queues nor scanning information boards, yet never unaware of the human traffic. I stay in by the wall, sidestepping the tide of those in genuine and deliberate transit, dazed yet somehow impervious, lost but not utterly bewildered. I drift just outside the echoes and thrums of journeys that are not mine, the endings and beginnings of missions, diversions, pilgrimages, expeditions. I observe lives unlike mine, full of imperative planned destinations, and I envy people this apparent conviction that their myriad tiny events, their moving toward events yet to be, are of some importance. Neither a proper impetus to travel nor a true purpose in remaining where I am falls my way. I lack reasons either to go or to wait, and this looks like failure in me.

Not that I am at all disgraceful. I am never drunk. I don’t mutter. I don’t carry my belongings in a bundle. It may be stained and tatty but I do have luggage, and I tend also to have an address, albeit it’s always temporary. I manage to keep out of hostels, mostly. Once a day I endeavor to eat at a table, wherever there’s a bargain (jumbo platter, hot drink, £3.99) and whether or not it’s a proper mealtime. Also once a day I’ll spend up to an hour nibbling on most of a sandwich and then wrap and pocket the crusts for later. I’m a hoarder, not a scavenger; I admit I never spend money on a paper (and actually it suits me not to read the news before it’s old and discarded) but I would not dream of polishing off abandoned cups of coffee. It’s true that I’m not above helping myself to forgotten gloves and scarves. Once in winter I took a man’s coat, left on a bench.

So my vagrancy is unspectacular. I wear a taint of rationing, that’s all. I have the thready, ashamed look of a reduced person who assumes there is worse reduction to come, who lingers until the last minute where it’s warmest before boarding the final bus or train, or who walks away from the dark station as the grilles rattle down because nobody waits for her in the evenings.

But tomorrow, though it’s hard for me to speak loud enough for you to hear, I’ll try again. I’ll take a sly, off-center interest in your moments of parting and greeting, look too closely at your clothes, the magazine you carry. Your polite glance when you ask if the seat next to me is free I’ll take as an invitation.

Yes! Though it’s none too clean.

No. Oh well, it’ll do.

I’m overglad to be spoken to, so that far too soon and whether you replied this way or not, I’ll turn to you with a remark too intricate, an anecdote too unlikely and revelatory. Yes, the pigeons here are awful, aren’t they? I met a woman once who got worms off a bench, from the droppings, she said. Filthy, it was. Much worse than this! After that she wouldn’t sit anywhere in public without spreading the seat with newspaper first. Once she stood an entire night because she hadn’t got any. But you can’t win, can you, because that played merry hell with her veins, which was worse than the worms. Or so she claimed.

And you’ll look away. You’ll dread that anyone might overhear and think something in you encouraged the likes of me to babble to you in this manner, in a hurrying voice and staring straight at your eyes, using the sincere and zealous hand gestures of a person who expects to be disbelieved or motioned to shut up before her story is finished.

I don’t blame you. I’ll watch you walk away just as I might have been about to ask if you knew where the nearest police station is, or if there is a telephone nearby, or a hospital. I know I’m unsettling. Maybe it’s because I know something you don’t, though it secures me no advantage. It’s only the knowledge that some other knowledge eludes me. It’s nothing more than an awareness of questions that the happenstance of some lives and not others—mine, say, and not yours—poses for some people and not for others.

Such as, where do I pick up the story of a life that should be over, but isn’t? If events have halted a life’s narrative as utterly as death itself, how do I go on as if I believed in mere continuation, never mind solace and amends? You won’t know. So I won’t detain you by saying, Oh, excuse me! Could you help? I’m afraid something has happened.

I won’t call after you to tell you how weary I am, I’ll settle back and wait out another day. To pass the time, from somewhere in my baggage I’ll bring out bundles of thumbed papers secured under rubber bands and I’ll fret over ordering and reordering them, rereading this or that grubby old letter as if it might contain something new. And I’ll sink into wondering again, asking myself the same questions and finding them still unanswerable.

27 Cardigan Avenue

living room

8th May

Dear Ruth

Were the flowers satisfactory? I just got white ones, you know I’m no good with colors. Were they the right thing?

Writing this isn’t my idea it’s Carole’s. You don’t know Carole.

Well can’t think of anything else for now.

Arthur

Did it begin that morning? If it did, could I have known? Suppose that morning the butter had been purple and the sparrows blue and flying backward, was I too preoccupied with writing my shopping list (

eggs, raspberries

) to notice? If clouds had arranged themselves over the garden spelling out a warning in big vapory letters and loomed through the window, might I have been turning away at that precise moment and failed to see? I go on wishing that if what happened was fated to happen I could have been given a second’s notice, just long enough to take a step out of its path. But that would amount to its not having been fated after all, and I would probably have missed such a warning, anyway. I had been unattuned to signs for so long.

Because of course it began long before the condom wrapper in the glove compartment. I must have missed those signs, the slight, prosaic symptoms of near-comic, midlife adultery: an unexplained and distant air of satisfaction, some extra fastidiousness about hair and fingernails, a renewed determination to lose some weight. Did he take longer to answer when I spoke to him? How many times did he look at me and wish he were with her, or slip away to ring her in a small, timed absence? I missed the little signs, but maybe I missed huge and laughably obvious ones, too. Maybe he had been living in a state of priapic delirium right under my nose but I had stopped seeing anything at all when I looked at him.