The Next Eco-Warriors (18 page)

Read The Next Eco-Warriors Online

Authors: Emily Hunter

Instead of sticking to the agreement, police, helicopters, and armored carriers began an eviction of sorts, ignoring pleas against violence. In the confusion of people fleeing or even trying to defend themselves with spears, many were shot and lay wounded on the battlefield. While eighty-five people were still missing after the incident, some returned to their communities after the battle; some were gone forever.

When questioned about the reasons for the protest, Solomón replied:

We do not accept the kind of “development” that the president offers us, because it is not sustainable, and it threatens the Amazon rainforest. If the government insists on sidelining us, we will no longer block roads but will instead draw our own limits

.

Our territory is our market, our mother. Everything we need for our survival is in the rainforest. That's why we are defending it with our lives. The struggle will continue until the laws are gone. What happens next is up to the government

.

He was referring to the many laws passed by the government to open up the Amazon to foreign oil and mining operations.

That night, we were lucky to find a hotel room in a small Amazon town that even had Internet. The next morning, we took off for Station 6, the oil facility in the heart of the rainforest that was another site of violence. We somehow got very lucky, as we passed through a number of military checkpoints and they never asked for ID. However, we were disappointed, arriving at Station 6 hours later.

We got there, finally, but the military troops who now ran the station refused to talk to us. Even worse, they got angry when I tried to take pictures, saying it wasn't allowed. We drove off, frustrated that we had come all that way for nothing.

When we were on our way back out of the jungle, our driver noticed an oil spill on the side of the road. We got out of the car and quickly found some people from the neighboring community who were also wondering what was going on. Gobs of oil, like a river of black, pooled in puddles on the side of the road. We managed to follow the oil stream up a hillside, which had been recently cut down. Scrambling to the top, the other photographer and I discovered all the trees had been cut down, and the ground was covered in sheen.

The issue of oil companies going into the Amazon didn't seem so theoretical anymore. Community members had been sharing their fears of oil companies coming in, taking away their land, and poisoning them. And now, here it was, happening before our very eyes. . .

.

We had found ourselves in the middle of an old-fashioned oil spill. Not far away, a crew worked on an exposed oil pipeline, as lots of young men picked up contaminated vegetation and tossed it into garbage bags. They stopped for a bit when they saw us but went back to work. A security guard by the pipeline spotted us. I worked quickly to get some photos and document the spill.

The security guard came by, telling us not to take photos. The other photographer began negotiating with him, distracting him. I got some more photos, but he had called in the military. Soon, a few soldiers arrived to tell us it was illegal to take photos, waving machine guns around. Intimidated, I

slowly came down the hill, where there was now a group of about thirty local villagers who had come by to see what was happening.

The villagers were very concerned about the oil pipeline leaking into the river and contaminating their source of food and water. Like us, the company and military wouldn't tell them what happened, or even what company they were from. The soldiers seemed to be working for the company, even doing their media relations for them, telling us we would have to direct any questions to their headquarters, a headquarters they wouldn't name. The villagers were distraught, and our chance visit would be their only way to let the world know.

The issue of oil companies going into the Amazon didn't seem so theoretical anymore. The whole time, community members had been sharing their fears of oil companies coming in, taking away their land, and poisoning them. And now, here it was, happening before our very eyes, almost unbelievable that it was so real, plainly in front of us.

This is why the people had started their fifty-five-day protest. It seemed they had very good reasons to want to protect their homes, families, ways of life. In total, more than thirty thousand people in the Amazon had participated in the protests, including communities like Bagua. With the news of what really took place, people around the world rallied to the cause, and in Peru, thousands of people marched in the streets against the government. In the end, the protest was successful, and the government backed down on many of the laws in question after huge domestic and international pressure was placed on Peru.

For me, after helping spread the word of what happened, I soon had to return to Canada. Being back at home, I sometimes felt a lot less useful, but I kept in contact with Peru and did many speaking events and media interviews about the massacre, continuing to tell the world what happened. It was important to share this story in Canada, as many of the mining companies in the Amazon are Canadian. And with Canada recently signing a free trade agreement with Peru to secure access to formerly remote areas, communities like the ones I was in have become expendable.

The case of Peru really challenges me to consider how the things we value and the way we live have an impact around the world. That will

be the defining challenge of our generation, and this is the message that many Indigenous Peoples in the Amazon and beyond are bringing to the world. Whether we as people are able to come together and deal with our crises—of racial violence, environmental justice, and climate change— will depend on our relationships with each other and our only home, planet Earth.

We are in a time where profound transformations of relationships are needed. What we need to do is consider how all our actions, every day, can contribute to the world we live in. We are all connected, and it's time we started living like it.

Considering this myself, I went back to Peru almost a year later. Many of the Indigenous communities were still suffering from the wounds inflicted, people were still in jail, Pizango was still in exile. Today, their biggest threat isn't from oil, however. It is from a Canadian gold-mining company trying to invade their territories. In the future, their real threat will continue to be from a world indifferent to their survival and the survival of our planet.

PHOTO BY SHADIAFAYNE WOOD

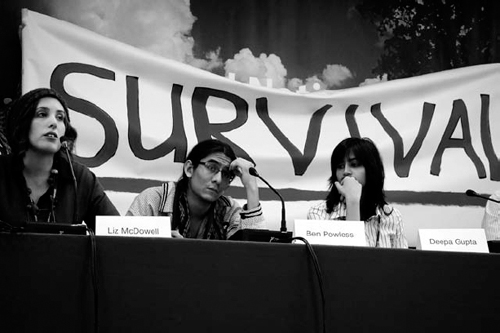

Ben Powless continues to support Indigenous Peoples across the world through his work with the Indigenous Environmental Network and freelance reporting

.

Thirty-eight

Thirty-eight Canada

Canada Survivor

Survivor

PHOTO BY BARBARAVEIGA

The Earth is not dying—it is being killed. And the people who are killing it have names and addresses

.

—U. UTAH PHILLIPS

WE WERE SITTING CROSS -LEGGED, staring up at one of those huge Mac trucks, one that was revving its engine just inches from our faces. It was one of those moments when all reason would have you get up and leave. This ten-ton truck could have crushed us like flies before it even reached second gear. But force wasn't going to win this battle; it was a classic case of peaceful civil disobedience in the tradition of Thoreau, Gandhi and Martin Luther King. We had strength in our weakness.

There were, after all, two other exits to the municipal yard that weren't being blocked. But the head of the Winnipeg Insect Control Department was determined to break through the blockade we had set up. It was a symbolic moment for both of us, and it had turned into a standoff.

The cops were playing nice, milling around and asking us politely to leave, knowing full well that we weren't going to do so unless it was in handcuffs or with a promise that the pesticide trucks would not leave the yard today.

The “fogging” trucks have been around as long as I can remember, driving through my neighborhood and leaving giant clouds of pesticides in their wake. It's just like a scene from one of those 1950s films of DDT trucks spraying clean-cut American kids and sunglass-wearing mothers just after World War II. But DDT was banned for its toxicity, most notably for its links to cancer

in humans and softening the shells of bird eggs. It's hard to believe that with this clear association in the public mind, the city of Winnipeg still dares run these same spray trucks in the 21

st

century, poisoning the citizens of our city with a different toxic chemical, ostensibly to save us from the evil disease-carrying mosquitoes that arrive every summer.

The truck drivers were clearly agitated. They were gunning their engines, releasing big clouds of black smoke. Then a friendly face arrived. He was a suit-wearing bureaucrat from the city and he invited us into his office to negotiate an end to the blockade.

Four of us agreed to follow him, while the rest stayed at the yard exit to maintain the blockade. He sat us down, offered us a cup of coffee and smiled, saying he understood why we were angry and that we had every right to make our opinion heard, but this wasn't the best way.