The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (50 page)

Read The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

By then, with the government line finished, Rat Portage had settled down to become a mild and relatively law-abiding community, but in 1880 it was the roughest town in Canada, the headquarters of the illegal liquor industry with eight hundred gallons pouring into town every month, hidden in oatmeal and bean sacks or disguised as barrels of coal oil. It was figured that there was a whiskey peddler for every thirty residents, so profitable was the business. “Forty-Rod” – so called because it was claimed it could fell a man at that distance – sold for the same price as champagne in Winnipeg from the illegal saloons operating on the islands that speckled the Lake of the Woods.

Here on a smaller and more primitive scale was foreshadowed all the anarchy of a later Prohibition period in the United States – the same gun-toting mobsters, corrupt officials and harassed police. One bloody incident in the summer of 1880, involving two whiskey traders named Dan Harrington and Jim Mitchell, had all the elements of a western gun battle.

Harrington and Mitchell had in 1878 worked on a steam drill for Joseph Whitehead but they soon abandoned that toil for the more lucrative trade. In the winter of 1879–80, a warrant was issued for their arrest at Cross Lake, but when the constable tried to serve it, the two beat him brutally and escaped to Rat Portage where the stipendiary magistrate, F. W. Bent, was in their pay. The two men gave themselves up to Bent who fined them a token fifty dollars and

then gave them a written discharge to prevent further interference from officials at Cross Lake. The magistrate also returned to Harrington a revolver that had been confiscated.

The two started east with fifty gallons of whiskey, heading for the turbulent little community of Hawk Lake where the railroad navvies had just received their pay. They were spotted, en route, by one of the contracting partnership, John J. McDonald (the same man who had once bribed Chapleau, the public works clerk). McDonald realized at once what fifty gallons of whiskey would do to his work force. He and the company’s constable, Ross, went straight to Rat Portage, got a warrant and doubled back for Hawk Lake.

They found Harrington and Mitchell in front of Millie Watson’s bawdy tent. Mitchell fled into the woods but Harrington boldly announced he’d sell whiskey in spite of contractors and police. The two men wrested his gun from him and placed him under arrest. Harrington then asked and was given permission to go inside the tent and wash up. Here a crony, bedded with a prostitute, handed him a brace of loaded seven-shot revolvers. Harrington cocked the weapons and emerged from the tent with both of them pointed at the constable. Ross was a fast draw; as Harrington’s finger curled around the trigger the policeman shot him above the heart. Harrington dropped to the ground, vainly trying to retrieve his guns. A second constable, McKenna, told Ross not to bother to fire again: the first bullet had taken effect.

“You’re damned right it has taken effect,” Harrington snarled, “but I’d sooner be shot than fined.” Those were his final words.

Magistrate Bent was removed from the bench the following week and the Winnipeg

Times

reported that “he is now actively engaged in the illicit traffic of selling crooked whiskey himself. He has now become an active ally [with] those whom he was at one time supposed to be at variance in a legal sense, whose pernicious vices he was expected to exterminate but did not.”

It was these reports, seeping back to Winnipeg, that persuaded Archbishop Taché of St. Boniface that the construction workers needed a permanent chaplain; after all, a third of them were French-Canadian Catholics from Manitoba. He selected for the task the most notable of all the voyageur priests, Father Albert Lacombe, a nomadic Oblate who had spent most of his adult life among the Cree and Blackfoot of the Far West. In November, 1880, Lacombe set out reluctantly for his new parish.

Father Lacombe was a homely man whose long silver locks never

seemed to be combed; but benevolence shone from his features. He did not want to be a railway chaplain. He would much rather have stayed among his beloved Indians than have entered the Sodom of Rat Portage, but he went where his church directed. On the very first day of his new assignment he was scandalized by the language of the navvies. His first sermon, preached in a boxcar chapel, was an attack on blasphemy.

“It seems to me what I have said is of a nature to bring reflection to these terrible blasphemers, who have a vile language all their own – with a dictionary and grammar which belongs to no one but themselves,” he confided to his diary. “This habit of theirs is – diabolical!”

But there was worse to come: two weeks after he arrived in Rat Portage there was “a disorderly and scandalous ball” and all night long the sounds of drunken revelry dinned into the ears of the unworldly priest from the plains. Lacombe even tried to reason with the woman who sponsored the dances. He was rewarded with jeers and insults.

“My God,” he wrote in his diary, “have pity on this little village where so many crimes are committed every day.” He realized that he was helpless to stop all the evil that met his eyes and so settled at last for prayer “to arrest the divine anger.”

As he moved up and down the line, covering thirty different camps, eating beans off tin plates in the mess halls, preaching sermons as he went, celebrating mass in the mornings, talking and smoking with the navvies in the evenings and recording on every page of his small, tattered black notebooks a list of sins far worse than he had experienced among the followers of Chief Crowfoot, the wretched priest was overcome by a sense of torment and frustration. The heathen Indians had been so easy to convert! But these navvies – nominal Christians all – listened to him respectfully, talked to him intimately, confessed their sins religiously and then went on their drunken, brawling, blaspheming, whoring way totally unashamed.

Ill with pleurisy, forced to travel the track on an open handcar in the bitterest weather, his ears ringing with obscene phrases which he had never before heard, his eyes affronted by spectacles he did not believe possible, the tortured priest could only cry to his diary, “My God, I offer you my sufferings.” Hard as frozen pemmican, toughened by the harshness of prairie travel and the discomfort of Indian tepees, tempered by blizzard and blazing prairie sun, the pious Lacombe all but met his match in the rock and muskeg country of Section B.

“Please God, send me back to my missions,” he wrote, but it was not until the final spike was driven that his prayers were answered. He had not changed many lives, perhaps, but he had made more friends than he knew. When it was learned that he was going, the workmen of Section B took up a large collection and presented him with a generous assortment of gifts: a horse, a buggy, a complete harness, a new saddle, a tent and an entire camping outfit to make his days on the plains more comfortable. Perhaps, as he took his leave, he reasoned that his tortured mission to the godless had not been entirely in vain.

*

Hewson was wrangling with Macdonald over the fee supposedly owed him for some newspaper work he had done for the Conservatives. When the party demurred at paying, the General threatened to horsewhip the Prime Minister on Parliament Square. He eventually settled, however, for “a neat pile of Bank of Montreal bills, clean and crisp,” to quote the Ottawa

Free Press

.

Chapter Eight

2

“Donald Smith is ready to take hold”

1

Jim Hill’s Folly

On one of those early trips to the Canadian North West in 1870, when he was planning his steamboat war against the Hudson’s Bay Company, James Jerome Hill’s single eye fastened upon the rich soil of the Red River country and marked the rank grass that sprang up in the ruts tilled by the squeaking wagon wheels. It was the blackest loam he had ever seen and he filed the memory of it carefully away in the pigeonholes of his complicated and active mind, to bring it out and caress it, time and again, and contemplate its significance. Soil like that meant settlers, tens of thousands of them. Settlers would need a railway. With Donald Smith’s help, Jim Hill meant to give them one.

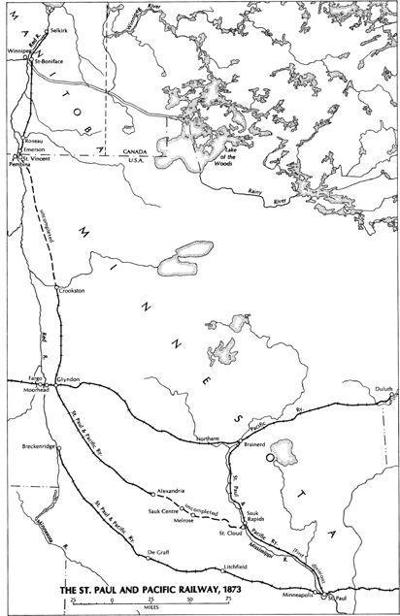

There was a railway of sorts, leading out of St. Paul in 1870. It was supposed to reach to the Canadian border but it had not made it that far. One of its branches ended at Breckenridge on the Red River, where it connected with the Kittson line of steamboats. Another headed off northwest to St. Cloud at the end of the Red River trail. An extension faltered north towards Brainerd, where it was supposed to connect with the main line of the Northern Pacific. But neither branch nor extension could properly be called a railroad. They had been built in a piecemeal fashion out of the cheapest materials – iron rails rather than steel, and fifteen distinct patterns of iron at that. Bridge materials, stacks of railway ties and other bric-a-brac littered the right of way. Nobody quite knew who owned what but the farmers along the line were helping themselves to whatever they needed to improve fences, barns and houses. As for the rolling stock, it was best described as primitive, the engines ancient and creaky, the cars battered and rusty.

The story of the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad is a case history in railway looting in the mid-nineteenth century, when anybody who promised to build a line of steel could get almost anything he asked. In four years of railway madness between 1853 and 1857, no fewer than twenty-seven railroad companies were chartered in the United States. One of these was the St. Paul line, first known as the Minnesota and Pacific. Its subsequent history is one of legislative corruption and corporate fraud, and the complicated story of its financing has few equals in railroad annals.

The villain in the piece was Russell Sage, the shadowy robber baron from Troy, New York, who with a hand-picked group of

“notorious lobbyists and swindlers” (to use Gustavus Myers’s term) corrupted the Minnesota legislature into handing over vast land grants and bond issues, the proceeds of which they pocketed through a variety of devices including dummy construction companies. In just five years the road was bankrupt though it had built only ten miles of line. The Sage group then coldly reorganized the bankrupt company into two new companies. By this device they rid themselves of all the former debts yet kept the land grant. They then proceeded to lobby for even more land. When they got that, they floated a bond issue of $13,800,000 in Holland. They diverted some eight million dollars of this sum to their own pockets and plunged the railroad into bankruptcy again.

In the early seventies the railway consisted of some five hundred miles of almost unusable track – “two streaks of rust and a right of way,” as it was contemptuously called. One of its lines – the section that was supposed to connect St. Cloud with the Northern Pacific by way of Glyndon – actually went from nowhere to nowhere, a phantom railroad lying out on the naked prairie with no town at the terminal end of iron and no facilities created to do business at the other; there was not even a side track. When Jesse Farley, the receiver in bankruptcy, arrived in 1873 to take it over, he found it in such bad condition that the battered old locomotive would not run over it. He had to inspect it by handcar.

Yet this was the line that Jim Hill coveted; and this was the line that would eventually make Jim Hill, Donald Smith, Norman Kittson and George Stephen rich beyond their wildest dreams and gain them both the experience and the money to build the Canadian Pacific Railway.

In St. Paul, Hill was the town character. He was looked upon as a likable eccentric and a notorious dreamer who would talk your ear off if you gave him half a chance, especially if he got on the subject of railways – though it was admitted that he

did

know something about transportation.

Indeed he did. He seemed to know something about everything. When Hill got into a project he got in with both feet; he wrestled with any new subject until he had mastered it and he had an uncanny knack of being a little bit ahead of everyone else. When he first went to work as a shipping clerk on the levee in the days when there was not a mile of railroad in the state, he used to amuse his fellow workers with wild predictions that the newfangled steam locomotives would one day replace river packets.

Hill was the kind of man who could look at a village and see a city or gaze upon an empty plain and visualize an iron highway. He took a look at St. Paul when it was only a hamlet and realized he was at one of the great crossroads of western trade. Accordingly he set himself up as a forwarding agent and began to study the movement and storage of goods. When the railway first came along Hill began to sell it wood, but he saw that coal would swiftly replace the lesser fuel and so he studied coal. He made a survey of all the available sources of coal and became the first coal merchant in St. Paul; he also sold the first bagged coal in town.

That

was not enough for Hill. He became an expert on fuel and energy of all kinds. He actually joined geological parties exploring for coal. Years later, when the great coal deposits were discovered in Iowa, it turned out that one-eyed Jim Hill held 2,300 of the best acres under lease. Until his death he was considered one of the leading experts on the continent on the subject of western coal.