The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (27 page)

Read The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Such hardships were commonplace. Fleming’s friend J. H. E. Secretan, a man who liked his food, was reduced to eating rose haws washed down with swamp water during a survey near Lake Nepigon in 1871. In the same year seven members of a survey supply party were lost near Jackfish River as the result of a forest fire so hot that the very soil was burned away. Only one body was found. Of the remainder there was no trace, save for six holes scratched out of a nearby swamp and apparently abandoned when the smoke grew too thick.

In the same area north of Lake Superior, the problem of supplies resulted in costly delays and bitter recriminations. Henry Carre, in charge of a party working out of Lac des Isles in the Thunder Bay area, found himself in country through which no white man had ever been. He would have finished his survey had he been properly supplied but had to turn back to Prince Arthur’s Landing, otherwise “I verily believe the whole party would have been starved to death.” William Kirkpatrick, working near Long Lake north of Superior the same year, had to take his party off surveying to pick blueberries to save their lives. For a week the group had nothing else to eat. In 1875, Kirkpatrick headed a party of more than thirty men locating the line from Wabigoon. Winter set in but no toboggans, tents, clothing or footwear arrived. The resourceful Kirkpatrick made forty pairs of

snowshoes and thirty toboggans with his own hands, fashioned a tent out of canvas and scrounged another one, made of skins, from the Indians.

In the Thompson River country of central British Columbia, forty miles out of Kamloops, Roderick McLennan’s survey party lost almost all of its pack animals in the winter of 1871. Eighty-six of them, McLennan reported to Fleming, died from cold, hunger or overwork.

An even worse winter expedition was the exploration launched in 1875 by E. W. Jarvis, who was charged with examining the Smoky River Pass in the Rockies. Fleming had already settled on the Yellow Head as the ideal pass for the railway, but this did not prevent him from carefully examining half a dozen others, just in case. Jarvis set off in January from Fort George with his assistant, C. F. Hanington, Alec Macdonald in charge of dog trains, six Indians and twenty dogs.

Both Jarvis and Hanington left graphic accounts of the ordeal, illuminated by uncanny episodes: the spectral figure of Macdonald knocking on the door of their shack in 49 below zero weather, sheathed in ice from head to toe; the lead dog who made a feeble effort to rise, gave one spasmodic wag of his tail and rolled over dead, his legs frozen stiff to the shoulders; and the auditory hallucinations experienced one night by the entire party – the distinct but ghostly sound of a tree being felled just two hundred yards away but no sign of snowshoes or axemanship the following morning.

The party travelled light with only two blankets per man and a single piece of light cotton sheeting for a tent. They moved through a land that had never been mapped. A good deal of the time they had no idea where they were. They camped out in temperatures that dropped to 53 below zero. They fell through thin ice and had to clamber out, soaked to the skin, their snowshoes still fastened to their feet. They stumbled down box canyons and found the way blocked by frozen waterfalls, two hundred feet high. They suffered from

mal de raquette

, a kind of lameness brought on by the constant need to wear snowshoes. One day they experienced a formidable change of temperature – from 42 below zero to 40 above – and this produced a strange exhaustion, as if they were suddenly plunged into the tropics. One morning, while mushing down a frozen river, they turned a corner and saw an abyss yawning before them: the entire party, dogs and men, were perched on the ice ledge of a frozen waterfall, two hundred and ten feet high; the projection itself was no more than

two feet thick. One evening they made camp below a blue glacier when, without warning, great chunks of it gave way; above them they beheld “masses of ice and rock chasing one another and leaping from point to point as if playing some weird, gigantic game.” A chunk of limestone, ten feet thick, scudded past them, tearing a tunnel through the trees before it plunged into the river.

By this time it was March. Dogs were dying daily. Even the Indians were “in a mournful state of despair, declaring that they … would never see their homes again and weeping bitterly.”

On March 15 Hanington described Jarvis as “very thin, very white and very much subdued.” When they had reached the Smoky Pass, some time before, Jarvis had entertained grave doubts about proceeding further, but Hanington had said he would rather starve than turn back. It began to look as if he would:

“I have been thinking of ‘the dearest spot on earth to me’ – of our Mother and Father and all my brothers and sisters and friends – of the happy days at home – of all the good deeds I have left undone and all the bad ones committed. If ever our bones will be discovered, when and by whom. If our friends will mourn long for us or do as is often done, forget us as soon as possible. In short, I have been looking death in the face.…”

Jarvis described “the curious sensation of numbness, which began to take hold of our limbs,” as they pushed slowly forward on their snowshoes, giving the impression of men marking time in slow motion. Yet they made it. Hanington had lost 33 pounds; Jarvis was down to a bony 125. The food given them when they finally reached Edmonton produced spasms of dysentery and vomiting. Still they kept on, setting off once more across the blizzard-swept prairie for Fort Garry. All told, they spent 116 days on the trail, travelling 1,887 miles, 932 of those miles on snowshoes and 332 of them with all their goods on their backs, the dogs being dead.

Why did they do it? Why did any of them do it? Not for profit, certainly, there was little enough of that; nor for adventure, there was too much of that. The answer seems clear from their actions and their words: each man did it for glory, spurred on by the slender but ever-present hope that someday his name would be enshrined on a mountain peak or a river or an inlet, or – glory of glories – would go into the history books as the one who had bested all others and located the route for the great railway.

2

The bitter tea of Walter Moberly

One man who thought he had the route and who spent the twilight of his life recalling, with increasing bitterness but not always with great accuracy, the attempts to “humbug” the route away from him, was Walter Moberly.

Moberly was working in Salt Lake City in 1871 when the news came of the pact with British Columbia. He went immediately to Ottawa where his enemy, Alfred Waddington, was already trying to promote a railway company. Moberly hated Waddington – the verb is not too strong – for the same reason he hated anyone who tried to promote a railway route to the Pacific that did not agree with his own conception. Waddington was a fanatic on the subject of Bute Inlet as a terminus for the railway. It was “his” inlet; he had explored it. Moberly was equally fanatical on the subject of the Eagle Pass, the Fraser River and Burrard Inlet. That was

his

inlet; he had trudged along its shores before any white man had settled there. He apparently viewed the massacre of Waddington’s survey party as a salutary act, for he was incensed when some of the murderers were hanged.

Surveyors tended to fall in love with the virgin territory they explored. Moberly had fallen in love with the Eagle Pass, which he had discovered and named in the summer of 1865 as a result of watching a flight of eagles winging their way through the mountains. Moberly knew that eagles generally follow a stream or make for an opening in the alpine wall. Eventually he followed the route of the birds and discovered the pass he was seeking through the Gold Range. According to his own romantic account, he finally left his companions, after a sleepless night, and made his way down into the valley of the Eagle River, where he hacked out a blaze on a tree and wrote the prescient announcement: “This is the Pass for the Overland Railway.”

Moberly had gone to school in Barrie with a tawny-haired, angular girl named Susan Agnes Bernard. In Ottawa, Susan Agnes, now Lady Macdonald, invited her former schoolmate to lunch at Earnscliffe, the many-turreted residence on the Ottawa River. Here, the weathered surveyor with the long, ragged beard and the burning eyes pressed his particular vision of the railroad on the Prime Minister of Canada. He insisted, with superb confidence, that he could tell Macdonald exactly where to locate the line from the prairies to the seacoast. Not only that but “you can commence construction of the line six weeks after I get back to British Columbia.”

“Of course,” Moberly added, “I don’t know how many millions you have, but it is going to cost you money to get through those canyons.”

Macdonald was impressed. Moberly was a fighter who came from a family of fighters. He was half Polish: his maternal grandfather had been in command of the Russian artillery at Borodino. His father was a Royal Navy captain. As a young engineer working on the Northern Railway, Moberly was fired by tales of the frontier which he heard first hand from Paul Kane, the noted painter of Indians. The Fraser gold rush of 1858 lured him west. It was Moberly who helped lay out the city of New Westminster in 1859. It was Moberly, too, who located, surveyed and constructed part of the historic corduroy road from Yale to the Cariboo gold-fields. He was a better surveyor than a businessman. The project left him with debts that took eight years to pay off. Moberly, like so many surveyors of that day, was also in politics, but he resigned his seat in the colonial legislature to take the post of assistant surveyor general for British Columbia. It was in this role that he discovered the Eagle Pass in the Gold Range, later called the Monashees.

When he returned to the province, with the Prime Minister’s blessing, as district engineer in charge of the region between Shuswap Lake and the eastern foothills of the Rockies, he was in his fortieth year, supple as a willow and tough as steel. There was no better axeman in the country. His staying power was legendary: he had a passion for dancing and when he emerged from the wilderness would dance the night out in Victoria. He loved to drink and he loved to sing but, as his friend Noel Robinson recalled, “no amount of relaxation and conviviality would impair his staying power when he plunged into the wilds again.”

He was as lithe as a cat and had as many lives, as his subsequent adventures proved. Once, while on horseback in the Athabasca country, he was swept into a river and carried two hundred feet downstream. He seized an overhanging tree, hoisted himself from the saddle and clambered to safety. On a cold January day he fell through the ice of Shuswap Lake and very nearly drowned, for the surface was so rotten it broke under his grasping hands. Nearly exhausted from his struggle in the icy water, Moberly managed to pull the snowshoes from his feet, one in each hand, and by spreading out his arms on the ice, climb to safety. Once, on the Columbia River, he gave chase, in a sprucebark canoe, to a bear, cornered it against a river bank, put an old military pistol against its ear and shot it dead, seizing it by the

hind legs before it sank – all to the considerable risk and apprehension of his companions in the frail craft.

Moberly, in short, was a character: egotistical, impulsive, stubborn and independent of spirit. He could not work with anyone he disagreed with; and he disagreed with anyone who believed there was any other railway route to the Pacific than the one that had been developing in his mind for years. Moberly had been thinking about the railway longer than most of his colleagues, ever since his explorations in 1858. Now, thirteen years later, he set out to confirm his findings. He began his explorations on July 20, 1871, the very day the new province entered Confederation.

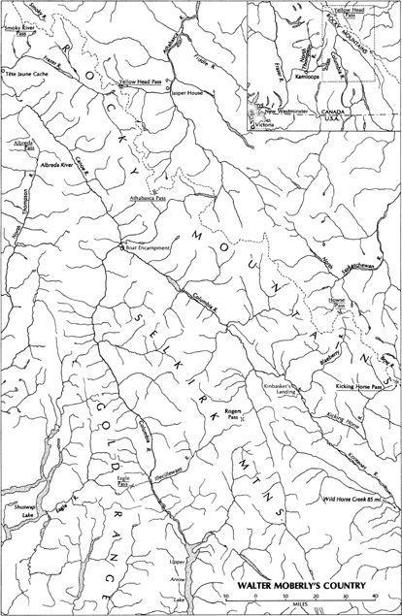

Moberly took personal charge of his favourite area bounded by the Eagle Pass of the Gold Range and the Howse Pass in the Rockies, just north of the Kicking Horse. Between these two mountain chains lay an island of formidable peaks – the apparently impassable Selkirks. It was in the hairpin-shaped trench around this barrier that the Columbia flowed, first northwest, then southeast again, until it passed within a few miles of its source. It was Moberly’s theory that the railway would cut through the notch of the Howse Pass, circumvent the Selkirks by following the Columbia valley, and then thread through the Gold Range by way of the Eagle Pass, which led to Kamloops and the canyons of the Fraser.

Moberly spent the next eight months in the mountains and trenches of British Columbia. He travelled down the olive-green Columbia with a crazy flotilla of leaky boats, burned-out logs and bark canoes, patched with old rags and bacon grease. He trudged up and down the sides of mountains, clinging to the reins of pack horses, accompanied always by a faithful company of Indians for whom he sometimes showed a greater respect than he did for white men. (“The Indian,” he wrote, “… when properly handled and made to feel that confidence and trust is reposed in him, will work in all kinds of weather, and should supplies run short, on little or no food, without a murmur; not so the generality of white men.”)