The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (10 page)

Read The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

This was nonsense. Fleming was far wordier than most politicians – a graceful public speaker, a voluminous diarist and author who, at his death, had some hundred and fifty articles, reports, books and pamphlets credited to his pen. As a writer, Fleming again was the gifted amateur. In his diaries and reminiscences he showed a sharp eye for descriptive detail, for subtlety of character and for the revealing personal anecdote. When he was too occupied to write himself, he took along a “secretary,” such as Grant, who would be sure to put it all down on paper.

Without this mountainous literary legacy, it is doubtful whether Fleming’s reputation as one of the greatest Canadians of the century would have survived. In his quiet yet thorough way, Fleming, the expert on communication, knew a good deal about personal public relations. There is a revealing story of Fleming’s curious role on

behalf of members of the Red River’s Canadian Party in the winter of 1862–63. He petitioned the Colonial Office and the Canadian government in their interest, representing himself as their delegate in Canada and England. His purpose, clearly, was to win public notice. Fleming paid the editor of the

Nor’wester

one hundred dollars to report that he had been given the post at large and enthusiastic public meetings. As the Governor of Rupert’s Land put it, “Mr. Fleming virtually appointed himself to represent a country and a people he had never seen.”

Finally, a decade later, he was about to see it, along with his companions. The prairie, which all had read about in Butler’s book, lured them on like a magnet. One night, after supper, realizing that it was only thirty-three miles away, they decided they

must

see it and pushed on through the night, in spite of a driving rain so heavy that it blotted out all signs of a trail. The three men climbed down from their wagon and, hand in hand – the giant Fleming in the centre, the one-handed Grant on the right and the wiry Macoun on the left – trudged blindly forward through the downpour, leading the horse, mile after muddy mile, until a faint light appeared far off in the murk. When, at last, they burst through the woods and onto the unbroken prairie they were too weary to gaze upon it. They tumbled, dripping wet, into a half-finished Hudson’s Bay store and slept. The following morning the party awoke to find the irrepressible Macoun already up and about, his arms full of flowers.

“Thirty-two new species already!” he cried. “It is a perfect floral garden.”

“We looked out,” wrote Grant, “and saw a sea of green, sprinkled with yellow, red, lilac and white. None of us had ever seen the prairie before and behold, the half had not been told us. As you cannot know what the ocean is without having seen it, neither in imagination can you picture the prairie.”

In Winnipeg, the party picked up a new companion, a strapping giant named Charles Horetzky, with brooding eyes and a vast black beard. This former Hudson’s Bay Company man was to be the official photographer for the party. Though everything went smoothly at the time, Horetzky was to be a thorn in Fleming’s side for all of the decade. Eight years later, the generally charitable Grant referred to him as “a rascal and … a consummate fool combined.”

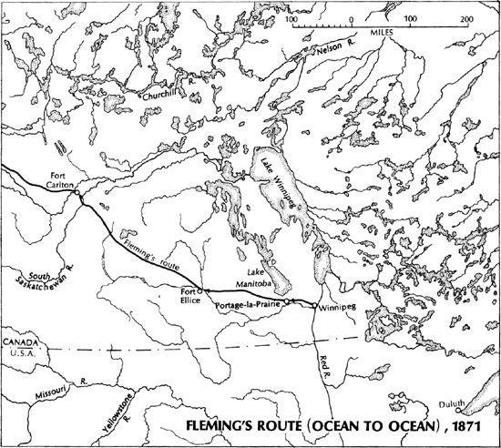

The party set out along the Carlton Trail – a small brigade of six Red River carts and two buckboards. The meticulous Fleming had figured that they must make forty miles a day for a full month and, leaving nothing to guesswork, attached an odometer to one of the carts. They rose at sunrise and travelled until dark in three spells a day. There were surprises all along the line of route, some of them pleasant, some terrifying. At one point they happened upon a flat plain, twelve miles wide, which was an unbroken mass of sunflowers, asters, goldenrod and daisies – an Elysian field shining like a multicoloured beacon out of the dun-coloured expanse of the prairie. At another they were struck by a hailstorm so strong that the very horses were flung to the ground and the carts broken. In this chill Hades, the stones pelting from the sky were so large that a single blow from one of them could stun a man.

All along the way, the travellers read and reread Butler’s account of his journey. In addition they had the newly published journal of an early Peace River explorer, which had been edited by Malcolm McLeod, an Ottawa jurist. McLeod was a man to be taken seriously. His father had been one of the early Hudson’s Bay men to cross the Rockies and he himself was familiar with that ocean of mountains. It was McLeod’s memorandum to the Colonial Secretary in 1862 that was credited with helping to force the sale of Rupert’s Land by the Hudson’s Bay Company.

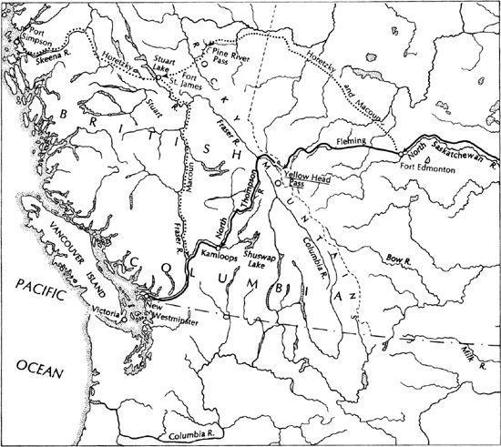

At Edmonton, the party split up. Fleming, intrigued by McLeod’s views on the agricultural resources of the Peace, suggested that Horetzky and Macoun go north and try to get through the mountains by way of that great river and then head for Fort St. James and thence to the coast. He and Grant would go through the old Leather Pass, now called the Yellow Head – after a tow-headed Indian – to meet one of Fleming’s survey parties.

For Macoun it became a bizarre journey. The hardy botanist was no stranger to punishment. As a schoolboy in Ireland he had been whipped unmercifully, almost daily. In spelling tests he would be given a slap on the hand with a ruler for every word he missed out of a selection of forty or more. It made him into something of a stoic; often he would take an undeserved whipping without a murmur to prevent a weaker boy from receiving it. But in the Peace River country, Macoun was subjected to a more subtle chastisement. It became increasingly clear, as the days wore on, that the swarthy Horetzky felt that the botanist was a drag on the expedition and had

determined to get rid of him by fair means or fout – or at least that is what Macoun believed.

It soon developed that Horetzky had determined upon a different course from the one Fleming had proposed for the Peace River exploration. He had decided to go through the mountains by a different pass, following the Pine River, a tributary of the Peace, and he did not want Macoun in the way. He tried to get the botanist to turn back but Macoun told him, stoically, that he would rather leave his bones in the mountains than fail.

He almost did. According to Macoun’s later account, Horetzky planned to lure him into the mountains, then leave him with the encumbering baggage to die or make his own way out while he, Horetzky, pressed on, lightly equipped, to new and dazzling discoveries. Horetzky was now giving orders to the Indians in French, a language Macoun did not understand. But the botanist was no fool; he clung to his companion like glue. The two made a hazardous 150-mile journey through the mountains in 26 below weather, carrying their own bedding and provisions and struggling with great difficulty over half-frozen rivers and lakes. They finally reached Fort St. James, the exact centre of British Columbia, on November 14.

It must have been a trying journey in other ways. The Hudson’s Bay factor at the fort quietly let Macoun know that Horetzky, who was only a co-director of the expedition, appeared to have taken full charge, ordering all sorts of luxuries for himself but only minimal provender for the botanist.

“I told him I did not care what I got,” Macoun later recalled, “as long as I got away from Horetzky with my life.”

Horetzky was already planning to push on westward through virtually unknown country to the mouth of the Skeena but Macoun had no intention of accompanying him. He was penniless by now, totally dependent on the charity of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Accompanied by two Indian guides, he fled south, wearing snowshoes seven feet long. He had never worn snowshoes in his life and soon abandoned them, content to flounder through the drifts which reached above his knees. Eventually, on December 12, he reached Victoria where he learned that, in his absence, his wife had been delivered of a fifth child. What she thought of her husband’s impetuous and extended summer vacation is not recorded.

Both Macoun and Horetzky produced books about their adventures and, eight years later, Horetzky followed up with a much more bitter pamphlet in which he attacked both Macoun and Grant. The

latter, he wrote, made “from the very beginning … strenuous efforts to ‘run’ the whole affair, as fast as possible, being, as he said himself, excessively anxious to rejoin his parishioners at Halifax by the 15th of November following.” Horetzky also became a zealous, indeed a fanatical advocate of the route he had first followed from the Pine Pass in the Rockies to the northern Pacific coast of British Columbia.

Grant made it back to his parish with two weeks to spare before the deadline of November 15. His journey with Fleming through the Yellow Head and down the Fraser lacked the cloak-and-dagger aspects of Macoun’s struggle. When the pair reached Victoria they found that one of their party had preceded them and was cadging free drinks from the press in the local saloons on the strength of tall tales about the expedition. “He had conjured up a canyon … twenty miles long where no canyon is or ever had been; had described us galloping down the Yellow Head Pass till arrested by the sight of quartz boulders gleaming with gold.”

The trip was not that exotic but it was certainly arduous. There were long swamps “covered with an underbrush of scrub birch, and tough willows … that slapped our faces, and defiled our clothing with foul-smelling marsh mud.” At times, in the Albreda area, the nine-year-old trail was buried out of sight by “masses of timber, torrents, landslides or debris.” The horses’ hooves sank eighteen inches into a mixture of bog and clay, but “by slipping over rocks, jumping fallen trees, breasting precipitous ascents with a rush, and recklessly dashing down hills,” the crossing of the Thompson River was reached. To the one-handed clergyman, the comfortable parish of St. Matthew’s must have seemed to have been on the far side of the moon.

It was, by any standard, an impressive journey that he and his companions had made. In 103 days of hard travel they had come 5,300 miles by railway, steamer, coach, wagon, canoe, rowboat, dugout, pack and saddle horse and their own sturdy legs. They had made sixty-two camps on prairie, river bank, rock, brush, swamp and mountainside; and they were convinced that the future railway would follow their route across the Shield, up along the Fertile Belt and through the Yellow Head Pass, which was Fleming’s choice from the moment he first saw it. This physical accomplishment was magnificent but its subtle concomitant was far more significant: in the most graphic and dramatic fashion, the clergyman and the surveyor had given the Canadian public a vision of a nation stretching from sea to sea.

7

The ordeal of the Dawson Route

It was one thing to have an itch to go west. It was quite another to get there. At the start of the decade, the would-be homesteader had a choice of two routes, both of them awkward and frustrating. He could take the train to St. Paul and thence to the railhead and proceed by stagecoach, cart and steamboat to Winnipeg; or he could take the all-Canadian route by way of the lakehead and the notorious Dawson Route.

The rail route was undoubtedly the most comfortable, though “comfortable” in those days was a comparative word. The Miller coupling and the air brake had not yet been invented so that passengers were jolted fearfully in their Pullmans. Having reached St. Paul by a series of fits and starts – for there were many changes and few through lines – the weary traveller could figure on at least another week before arriving at Winnipeg. The service on the St. Paul and Pacific Railroad was, to put it charitably, erratic. The faltering line, plagued by bankruptcies and plundering, ran to nowhere in particular, the exact location of the railhead being at all times uncertain and the condition of the rolling stock bordering on a state of collapse. “Two streaks of rust and a right of way,” they called it. Who would have believed that this comic opera line would one day become the nucleus of the two greatest transcontinental railways – the Great Northern and the Canadian Pacific?

Once at the end of track, the passengers hoisted all their worldly belongings onto a four-horse stage and bumped along through clouds of acrid dust and flocks of whirring prairie chickens towards the steamboat landing at Twenty-Five Mile Point. Along the trail one was likely to encounter hordes of Winnipeggers travelling, a family to a cart, to St. Cloud – “Father, mother and a troop of frowzy-headed, brown-faced children, who, though shoeless and hatless and half-naked, are as happy as larks singing in the meadows.”