The Napoleon of Crime (37 page)

Read The Napoleon of Crime Online

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #Biography, #True Crime, #Non Fiction

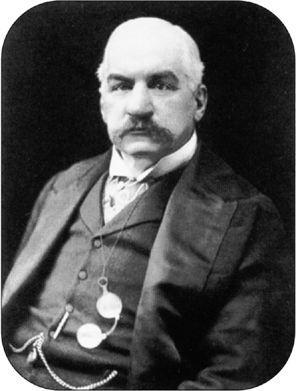

J. Pierpont Morgan, fabulously wealthy American financier and art collector, who vowed to get his hands on Gainsborough’s

Duchess of Devonshire

, and did.

Professor James Moriarty as drawn by Sidney Paget in

The Strand

magazine, December 1893. “He is extremely tall and thin, his forehead domes out in a white curve, and his two eyes are deeply sunken in his head … his face protrudes forward and is forever oscillating from side to side in a curiously reptilian fashion.”

“A personal contest between the two men ended … in their reeling over, locked in each other’s arms … the most dangerous criminal and the foremost champion of the law of their generation.” Sidney Paget’s illustration for

The Strand

, December 1893.

TWENTY-FIVE

Moriarty Confesses to Holmes

W

orth had come to Chicago with the sole intention of opening negotiations for the return of the Gainsborough, which was now safely hidden in the old Saratoga trunk in McCoy’s Hotel. But while the two men talked, a confessional bond seemed to grow between the burly detective and the visibly aging thief. As Worth candidly admitted, he had never placed himself “in the hands” of another human being; his entire life had been devoted to controlling others. But now he did so utterly, to the man who should have arrested him on the spot. Instinct drew them together, for they had long inhabited the same universe, even if they traveled from opposite directions: the crook who was a man of honor; the man of principle who was now bending the law to its limit. It was a strange meeting of minds.

Their “chat” lasted the rest of the day, and then long into the evening. They met again at Pinkerton’s office the next day, and the next. Instead of getting down to business, Worth found himself unburdening his past, partly out of vanity but partly, it seems, out of a need to explain and justify the strange, crooked paths his life had taken. He summoned up the extraordinary rogues’ gallery that was his acquaintance of the last forty years: Kitty Flynn, Piano Charley Bullard, the Scratch, Old Junka, and the loathed Shinburn, laying before Pinkerton “

in gossiping frame of mind” a picaresque roster of the international criminal underworld, and his own distinguished role in it. Worth talked of his Civil War days, his experience of Sing Sing, his thievery in New York, Boston, London, and Paris, the robbery of the diamond convoy in South Africa, and, most crucially, the theft of Gainsborough’s

Duchess of Devonshire

, which he had jealously guarded for more than two decades but which now must be returned, to end the chapter. He was ill, he explained, perhaps dying. His words echoed his pathetic reverence for the object to which he had mortgaged his life and liberty: “

The Lady should return home.”

At the end of their three-day interview, Pinkerton was exhausted, exhilarated, and staggered by the sheer range of Worth’s exploits, and the strange combination of pride and melancholy with which he had recounted them. “

I consider this man the most remarkable criminal of his day,” Pinkerton wrote after Worth had departed. “This was a most extraordinary meeting … We talked very freely about matters in Europe for the last twenty years, and without hesitation spoke of numerous robberies in which he had been engaged … he talked in a general way about almost every big robbery which had taken place in Europe, and his conversation was very interesting indeed.” In addition to his large heart, Pinkerton was blessed with a prodigious memory. When Worth slipped out of his office and vanished once more, Pinkerton sat down and committed to paper, sixteen sheets of it, the bizarre interview that had just taken place.

Worth began his confession with some complimentary reminiscences, according to Pinkerton, saying “

he had always fancied me and found that I was a man who kept his own counsel and that he had always felt a kindly feeling towards me. How much flattery there was in this I am not prepared to say.” There was some, certainly, but also genuine admiration. Worth recalled how he had tried to give the detective a number of presents, but these had always been turned down. In particular he remembered “

a very handsome snuff box, a unique thing,” which he had wanted to send the detective “as a memento of old times,” but he had finally thought better of it, since it was “something that was so unique that it might attract attention.” It was also almost certainly stolen. Pinkerton maintained an incorruptible mien. “I told him I was glad he did not do it; that I did not want him to send me any presents.”

“Were you afraid that I was trying to job [bribe] you?” Worth laughed.

As Worth relaxed, he began to describe, in no particular order, his many crimes. The Boylston Bank robbery, he reckoned, was so long ago that he was probably safe. “

Of course you cannot tell,” he added nonchalantly. “I wouldn’t want to be tried on it, although thirty years have elapsed.” He described how he had sprung the members of his gang from the Turkish jail, how he and Bullard had set up the American Bar only to see it raided and closed on Pinkerton’s instigation. He shrugged and added, by way of no hard feelings, “I was beginning to recognize the fact that the American Bar would not be a success in the way I wanted.”

From there Worth moved on to minute descriptions of the diamond convoy robbery, the Ostend train robbery, his narrow escape from the Montreal police, and the debacle in Liège. His memories were spiced with vitriol as he recalled the treachery of Junka Phillips and Little Joe Elliott, the cruelty of Shinburn, and what he perceived to be his hounding “like a human tiger” by John Shore of Scotland Yard. The ferocity that simmered in Worth erupted as he recalled the times he had been betrayed, and his solitary belief in his own virtue. “He is quite a roast in his way on most everybody,” Pinkerton observed.

When the conversation turned to his own family, Worth grew mournful. Again he blamed others, and fate, describing how his former accomplice, Johnny Curtin, had seduced his wife, introduced her to drink and drugs, and stolen every penny she had. “I asked him where she was now,” Pinkerton wrote, “

and he said with tears in his eyes that the poor little soul was in the insane asylum, crazy, and would never come out … he was very bitter.” With the talk of his family, Worth’s poise seemed to deflate. The “brutal” prison treatment in Belgium had left him a physical wreck, he explained. Every day he suffered from “hemorrhages in the head,” and he was rapidly losing weight.

“He said he is going into the hands of a specialist as quick as he could to stop the hemorrhages; that if he does not have a hemorrhage every day he has terrific headaches; he blames it on the prison fare he got in Belgium. He said that he bled nearly half a pint of blood on Saturday morning,” Pinkerton told his brother.

With a quick piece of mental arithmetic Pinkerton worked out that the melancholy fellow before him by his own account had stolen more than four million dollars in the preceding thirty years. Where had all the money gone? “

He said that he had lived recklessly, speculated, gambled, dissipated, and had ran through it, but he remarked to me that if he ever got hold of a couple hundred thousand dollars again that nobody would get it away from him: that he would come back, buy a home and settle down with his children.”

Now thoroughly sorry for himself, Worth heaved a sigh. “I realize I am getting to be an old man, but there are one or two things I have yet to do that will get me sufficient money to provide for my family. That is all I have left to do. Then I shall quit.”

Finally, after several hours of nostalgia, riveting for Pinkerton and therapeutic for himself, Worth had arrived at the crux: the matter of the Gainsborough. Yes, he admitted, he had stolen the painting and kept it all these years. It had been a spur-of-the-moment decision intended to wangle his brother’s release from prison, but in the end it had changed his life. Worth was no longer reminiscing now, but haggling in earnest.

“

Of course I want to get some money out of it and I want you to get some money,” he went on. “I know you are an honorable man and that you will not make it any other way excepting legitimately, but I think it would be legitimate for you to make the money by restoring this picture to its owner,” he declared, and then sat back to observe the effects of this speech on the detective.

But Pinkerton was not to be drawn into a deal so easily. “I told him … that under no circumstances could we undertake anything of the kind; that it would be against everything we ever did and against every principle on which our business was conducted.”

Worth tried again with a little oblique flattery. “

The great Supt. Byrnes would have given his finger nails to have the opportunity to do what I am offering you but who could trust that kind of swine; nobody will trust them.”

Now Pinkerton gave some ground. “There might be other people in our business that would gladly attempt to do anything of that kind,” he conceded.

For a while they discussed various possible intermediaries. Worth said his sister Harriet had married a legal man named Lefens, “a sort of office lawyer [who] drew up deeds and documents and things of that kind,” but he doubted his “brother-in-law had weight enough to do it.” Who would Pinkerton recommend? he countered cannily.

“I told him there were plenty of people who did have weight enough to do it … that I would not advise Howe or Hummel or people of that kind who were liable to keep the whole proceeds of the matter or possibly tip him off to the police.”

Worth abruptly changed tack, pretending to abandon the whole idea of returning the Gainsborough. “He said he was sorry that we could not see our way clear to take hold of the thing but that he thought I was right in the premises: that it might make a stir and place us in a bad light with the London police.” Now it was Pinkerton’s turn to make a move in the delicate minuet. “What condition is the painting in?” he asked, with as blasé a manner as he could muster. Worth replied, with equal insouciance, that “he was satisfied the picture was intact.” And what, continued the detective, of the stories that he “had recently heard of a picture being discovered in some lodgings which was moss-eaten and mildewed and which was supposed to be the picture of the Duchess of Devonshire?” Worth responded that he, too, had read such accounts and could not explain it except to say that “

somebody was faking a painting and trying to put it off for the genuine one.”

Deliberately wandering from the subject, Worth suddenly began talking of a burglar-alarm system he was currently working on. “He said sometime he would give me the result of something he is studying up in the way of burglar protection by electricity: it is unique and unheard of,” Pinkerton reported. If the detective found it unusual to be discussing the latest burglary-prevention devices with one of the world’s most wanted felons, his notes do not betray him.