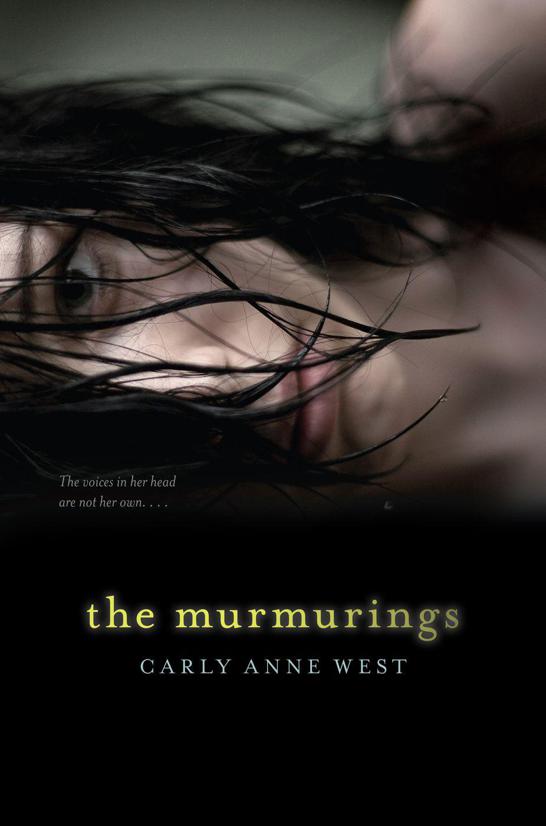

The Murmurings

Authors: Carly Anne West

Thank you for downloading this eBook.

Find out about free book giveaways, exclusive content, and amazing sweepstakes! Plus get updates on your favorite books, authors, and more when you join the Simon & Schuster Teen mailing list.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/teen

For Matt, always

Sun slides through bars, painted stripes of life on slick walls.

Glittering blue and amber eyes track blackness, eyes starved for prey.

I fit like a knife in the pocket of him.

Paper cups overflow with ups and downs.

I feel mostly sideways.

He says it can’t all be about what’s Taken.

I say there’s shelter in the West’s wickedest town but it won’t last.

He says there’s a chance.

I say, What’s the point?

He points to me.

I’

M SUPPOSED TO WONDER WHY

Gregor Samsa is a cockroach. Not how.

Why.

That’s the way Mrs. Dodd says we need to think if we’re going to analyze

The Metamorphosis.

Otherwise, the

how

gets distracting. Apparently, Franz Kafka didn’t want us questioning

how

it’s possible that some guy could wake up one morning as a cockroach. We’re supposed to focus on

why

he would be a giant, hideous insect, to ask

why

it had to happen to him and nobody else, to wonder

why

his family doesn’t care.

It feels pretty familiar, actually: all those

why

questions, that whole family-not-caring thing. Except that my mom probably wouldn’t notice if I grew antennae and a couple of extra legs, let alone take notice enough to throw apples at me across

the dining room table. As much as I want to listen to what Mrs. Dodd is saying about Gregor Samsa and cockroaches, all I can think about is how I wanted my junior year to feel different. Maybe more like it was happening to me and not someone else. Maybe just . . . quieter. Nell was always the outgoing one. I liked being the sister of someone who was popular. It came with fringe benefits. No one teased me if I sat in a corner at lunch with a book, rather than at a table with friends. After Nell went into the hospital, though, everything changed. All of her so-called friends treated her like a leper. And now, I’m someone to be feared by association.

“And what’s the significance of Grete, the sister? Anyone?”

In a way, it’s better. Even if someone tapped me on the shoulder—some bland-looking new girl who didn’t know anything about Nell, someone who didn’t know that my mom drinks like it’s her job, that I can’t talk to my dad about it because I don’t even know who he is and probably never will—and told me she wanted to be my best friend, what would I tell her? That I’m the girl whose sister heard whispers that weren’t quite words, and saw things so dark they took away her light? That she was really good at hiding it from everyone but me? That Nell cut herself and ran away from her institution with some orderly named Adam Newfeld, and that no one saw her again until her body was

found in Jerome, Arizona? That the police haven’t found the orderly—who was probably the last one to see her alive—not that they’ve been trying very hard? That when I went to Jerome a week later to see where they found Nell’s body, I felt like I was being watched the whole time, and when I returned to my car, Nell’s journal was lying on the front seat?

“Why does Kafka pay so much attention to the father figure? Come on. Someone knows.”

Or best yet, would I tell this pretend friend of mine that I’m starting to hear things too, just like Nell did before she got worse? Would I tell her about the thing in the mirror from that night?

“Sophie? You look deep in thought. Why don’t you share what’s on your mind?”

“The voice,” I say.

I hear shuffling behind me. A chair creaks under shifting weight. Someone snickers. I swear I hear “freak” coughed. It wouldn’t be the first time.

“Hmm, can you expand on that a little?” Mrs. Dodd’s face is puckered with concern.

She thinks I’m getting at something and wants to get there with me. I swear Mrs. Dodd would take anything I said as gospel. She always gives me credit for understanding more than I do. Why she thinks I’ve got so much figured out is beyond me.

I take a stab at it. “Er, uh, the voice is important for explaining . . . his anger?” Gregor seems mad enough. I mean, if I woke up tomorrow and I was a giant insect, I’d be a little more than pissed.

Still, I wonder if it’s worse to wake up and realize that your sister’s dead, or that you’ll probably wind up just like her. I wonder if that’s not a hundred times worse.

“Okay . . . ” Mrs. Dodd seems to chew on my words for a minute, then she swallows. Inspiration arrives. “Yes. Okay, anger. Absolutely. And this is the root of Kafka’s imagery. Very good. Now, who can take it from here?”

Sure, why not? Anger’s at the root of a lot of things.

That’s when a memory grips me like a cramp, taking over my body and making me focus on that one singular pain. It’s in reaction to a word: “root.”

Every part of me remembers the tree roots bulging from the ground in Jerome. The roots of the tree that held Nell upside down amid its high, sprawling limbs until the elderly sheriff found her. She was in a position so unnatural that I still can’t fully believe the report. But what I remember most is the feeling of my foot curving over the root of that goddamned tree.

I shudder, knocking my copy of

Franz Kafka’s Collected Works

to the floor with a thud loud enough to attract the

attention of the entire classroom. The snickering resumes. I look around, but nobody looks back. Like they’re afraid I’ll turn them to stone.

“Sorry,” I mutter to no one in particular and lean for the book, which is just out of my reach. Mrs. Dodd is talking about Gregor Samsa’s violin-playing sister, but all I hear is

sister, sister, sister

.

My head starts to swirl, and I’m so sure I’m going to throw up that I don’t even ask Mrs. Dodd for a hall pass. I don’t say a word. I just get up and charge to the front of the room.

“Sophie, are you—?”

I’m out the door before she can finish.

My cheeks are tingling by the time I enter the restroom. I push into the nearest stall (I don’t even scan to see if I’m alone. There’s no time) and promptly lose my breakfast: cottage cheese, cantaloupe, and half of a cinnamon-raisin bagel. I’m sure I’ll never eat any of those foods again for as long as I live.

“Oh God,” I mumble, shivering as I hear my words echo back to me in the dank bathroom.

I emerge from the stall and nearly jump right back into it when I see my reflection. I look like hell. In this light, my hair is less “chocolate auburn,” as the box suggested, and more purple. Which matches the circles under my eyes. My eyes

are deep-set as it is, so it sort of looks like my skull has swallowed them. My face is thinner than it used to be. I haven’t had much of an appetite since Nell died.

Nell.

Nell is dead.

My sister is dead.

There’s a faucet dripping. The rhythm is steady, and soon my heart begins to beat in time with it. Then there is nothing. It’s as if all sound is pulled from the bathroom with the intake of a breath.

After a moment, sound returns, focused in my right ear, like a hand cupping the air beside my head.

Murmuring.

The sound is so close, yet I can’t make out the words. But it wants to be heard.

“Sophie, what is it? What’s the matter?”

Mrs. Dodd stands in the open doorway, her hay-colored hair swishing as the door clangs shut behind her. The murmuring is gone. The faucet is dripping again. A tiny spot on the mirror distorts my reflection—a tiny spot that wasn’t there a minute ago.

It happened again.

“It’s . . . ” I start to say.

If I was going to tell anyone, it would probably be Mrs.

Dodd. She reads Poe and Tolstoy, and understands the poetry of Lord Byron and even Nietzsche. She once told us that when she reads Dostoevsky, she can almost hear the author breathing with her. She also gave me my very own copy of T. S. Eliot’s

The Waste Land

—my sister’s favorite—after Nell died.

“It’s nothing,” I say. “I-I’m sorry.” I start to leave, but she stops me.

“Easy. It’s fine. You know you can always talk to me, Sophie, if you need to.”

She’s trying to sound casual, but her face is scrunched up with worry.

“I’m fine.” My voice comes out a little too loud, echoing in the bathroom like a vocal pinball. “Hey, aren’t you supposed to be teaching?”

Her face finally relaxes when I say this. She’s the only teacher I feel comfortable talking to like she’s not a teacher. Maybe because she’s never treated me like just another student.

“I figured it wouldn’t take much to get you back in the classroom. I know how much you love Kafka,” she says as she pushes the door open for me.

I don’t have the heart to tell her I used to love him. Until he and every other author started making me think of Nell.

Back in the classroom, I return to my seat as quickly as

possible and fail to block out the whispers coming from Nell’s former friends. I try to tell myself that the murmuring isn’t getting louder, more insistent. I tell myself it’s not happening more frequently.

And mostly, I tell myself that I didn’t see the mirror start to ripple where my face was, like something was behind the glass, trying to get out.

• • •

The final bell for fifth period is already ringing as I throw my nearly uneaten lunch away. Now that I just don’t give a shit, tardiness is a new habit I’ve developed. Besides, rushing anywhere in Phoenix’s autumn heat only makes you sweat more than usual. The Sweep Monitor will catch me today, like he has every other day since the start of the school year.

“Sophie D.,” says a deep voice from behind me. The Sweep Monitor.

Sweep is a holding tank of delinquency where the kids who aren’t responsible enough to get to class before the door shuts get sent. Only the unluckiest of teachers, usually the football coach, Mr. Tarza, is assigned to babysit the Sweep room. Usually one of his junior varsity players gets stuck playing glorified dogcatcher. This month it’s been Evan Gold, and he’s on me like a hawk. A cute hawk, but still.