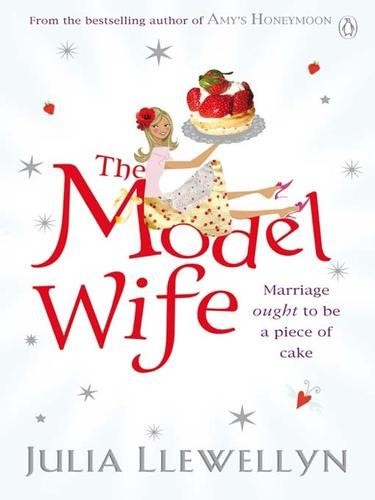

The Model Wife

Authors: Julia Llewellyn

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Romance, #General

The Model Wife

JULIA LLEWELLYN

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 2 5 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – no 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published 2008

Copyright © Julia Llewellyn, 2008

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-191156-4

For Clemmie

Acknowledgements

The Oscar bit no one reads, but profound thanks as always to Mari Evans and all the wonderful team at Penguin, especially the brilliant Natalie Higgins, Liz Smith and Ruth Spencer. To Lizzy Kremer and all at David Higham. Everyone at Channel

4

News for advice – especially Jon Snow. Victoria Macdonald was a brilliant help as always. Any resemblance to the

Seven Thirty News

is purely coincidental and mistakes are all my own. To Michaela Byrne – thank you for your essay! To Jana O’Brien, Hannah Coleman and above all Kate Gawryluk, I couldn’t have written this book without you. To my parents, and to the Watkins family for all their love and support.

1

Poppy Price had always dreamt of marrying a handsome prince, of catching his eye across the crowded ballroom floor, of him approaching and asking: ‘Shall we dance?’ They would swirl round the floor all night to the strains of the ‘Blue Danube’ and the next morning, on bended knee, he would ask for her hand in marriage.

Things didn’t quite turn out that way with Luke Norton. The first time she saw him was on a damp Friday morning in June when she served him a double espresso. Poppy was twenty and working as a waitress in Sal’s, a grimy café in King’s Cross wedged between a shop selling Japanese comics and another selling organic beauty products. Poppy had recently taken the job because modelling assignments had been few and far between, and the rent needed to be paid on the tiny flat she shared in Kilburn with her old schoolfriend Meena.

Luke was sitting alone at a corner table, talking agitatedly into a mobile phone. When Poppy saw him, her stomach lurched as if she had leant too far over a cliff. Tall, dark with a broad jaw, he looked like the rugged hero of the black-and-white movies Poppy loved to watch: the kind of man who’d rescue you from a burning building or bundle you on his camel and carry you across the desert.

He was old, admittedly, nearer fifty than forty, but that didn’t bother her. As a model Poppy came across a lot of young men, handsome young men, but they were such lightweights: panicking if they thought they’d put on half a pound and sucking in their cheekbones when they looked in the mirror. Poppy wanted someone more solid than that, someone who could protect her from a world which seemed to be full of hard elbows and backbiting. Protect her in a way her father might have done, if she’d ever got the chance to know him.

‘Christ, Hannah, I don’t know if I can…’ Luke was saying, when a sour-faced woman three tables away bawled, ‘Waitress!’

‘Yes?’ said Poppy through gritted teeth.

‘I’ve been waiting ten minutes for my coffee. Where the hell is it?’

‘I’ll just check,’ Poppy said as serenely as she could. She stuck her head round the kitchen door. ‘Hey, Sal, hurry up with that coffee for table ten.’

‘You never ask me for a coffee for table ten,’ protested Sal, her very patient Portuguese boss, looking up from his copy of

Metro

.

‘I did. Ages ago.’

‘You didn’t. Poppy, you are a terrible waitress.’ But he was smiling, because it was hard not to smile at Poppy with her cropped blonde hair and saucer-shaped eyes the colour of the translucent minty cough sweets Sal was so partial to.

‘Oh sorry. Well, she’d like a latte.’

‘Coming up,’ Sal said. Poppy went back into the so-called dining room with its red-and-black laminate floor, Formica tables and framed photographs of the gardens of Madeira.

‘It’s coming,’ she said to the woman. To her disappointment, she saw the perfect man had been joined by an equally perfect woman. Perfect from behind, anyway. Poppy couldn’t see her face. She had black hair in a French plait and was wearing a very elegant pinstripe trouser suit. She was about to go and take their order, when a woman with a buggy stopped her.

‘Excuse me, do you have high chairs?’

‘Hannah’s giving me so much grief again,’ she heard the perfect man say. ‘She doesn’t want me to go to Germany for the elections because it’s Tilly’s sports day.’

The woman sounded exasperated. ‘Poor you. Doesn’t she realize this is your

career

? I mean it’s not like you were a house husband when she met you.’

‘Exactly. How does she think we can afford Tilly’s bloody ridiculous school? I…’

‘I

said

do you have high chairs?’

‘Oh! Yes. Of course. I’ll go and get you one.’ Ears straining to pick up more of the conversation, Poppy returned to the kitchen. Their one high chair was covered in smeary mush from the last baby who had sat in it. Poppy had meant to clean it, but she’d forgotten. Hastily, she wiped it down. As she hurried back into the dining room, she saw the perfect woman disappearing through the door. The perfect man was still sitting at the table, looking gloomy.

‘At last,’ said the woman with the buggy. ‘I thought you’d died.’ She lifted the baby out of the buggy. ‘Come on, darling. Now you can have some breakfast.’ Just then Mrs Angry yelled. ‘Waitress! This is getting ridiculous. Next time I’m going to Starbucks.’

‘Sorry,’ Poppy gasped. She hurried back to the kitchen and emerged with the latte.

‘About time,’ Mrs Angry snapped, ‘and if you’re expecting a tip, you’ve got another think coming.’

‘Sorry,’ Poppy repeated, her face flamingo.

‘And I’d like to order too,’ chirruped the woman with the buggy. ‘Two croissants, please, and a latte.’

She heard Luke clear his throat.

‘And if it’s not too much trouble, I’d love another double espresso.’

‘Oh, OK. Sorry. Sorry.’ She rushed into the kitchen, shouted the orders to Sal and rushed out again.

‘I’m so sorry. I thought I’d taken your order already,’ she said to the woman with the baby, who rolled her eyes and said nothing. Poppy turned to Luke. ‘I do apologize.’

He smiled so the corners of his eyes crinkled. ‘It’s fine. You’re cheering me up. I think you’re having an even worse day than me.’

The line she’d been daring herself to say rolled off her tongue: ‘Want to talk about it?’

‘You know I really wouldn’t mind.’

Buttoning her green mac, Mrs Angry approached them. Poppy braced herself for a bollocking, but she was smiling.

‘Excuse me, I’m so sorry to interrupt. But I’ve just realized, you’re Luke Norton. I had to let you know I love the programme. Only intelligent thing on television these days.’

‘Thank you,’ Luke said.

‘Er. So.’ The gorgon had transformed into a simpering southern belle. ‘Good luck. Sorry to bother you. I’m just such a fan.’

She bustled out. Luke ran a hand through his hair.

‘God, I hate it when that happens. So embarrassing.’

‘Are you on TV?’ Poppy asked.

‘I am.’ He smiled. Then he patted the chair vacated by the perfect woman.

‘Do you want to sit down?’

‘In a minute,’ Poppy said, flustered. ‘I’ll just serve this lady.’

So she served the croissants and – with no other customers in sight – sat down and talked to Luke for nearly an hour. He told her how he’d once been a war correspondent, reporting on conflicts from all over the world. How he was now the anchorman for the

Seven Thirty News

, which sounded extremely glamorous, though Poppy couldn’t say she’d ever watched it, and how he was writing a book about the history of the Balkans, which he hoped would be seen as ‘definitive’.

‘I’m sure it will be.’ Poppy nodded, not quite understanding what he was on about.

The woman with the buggy left, leaving no tip. Luke continued talking about his family, his three children, the way he was growing apart from his wife.

Poppy’s heart sank temporarily when she heard the word ‘wife’, but like a cork in water it immediately popped up again because their marriage was so clearly on the rocks.

‘It’s so difficult,’ he said. ‘I want to be a good father, but we married too young and we’re just not making each other happy any more.’

‘That’s so sad,’ said Poppy, thanking the Lord that Sal’s was such a terrible café they’d probably get no more customers until the lunchtime trickle, meaning she could carry on talking to Luke all morning.

He smiled at her. ‘You’re very sweet. What are you doing working in a dump like this?’

‘Well, actually,’ Poppy confided, ‘I’m a model. I just do this between jobs.’

She hated telling people what her job was, because they immediately looked her up and down, clearly thinking ‘too fat, too small, nose too squodgy’ – all the things booking agents muttered when she stood in front of them. Women made a sneery, scornful face; men eyed her like an expert from the

Antiques Roadshow

evaluating a Victorian dining table. Both sexes were clearly thinking ‘thick as a plank’.

But Luke simply smiled again. ‘I thought as much. It can’t be long before someone as beautiful as you hits the big time.’ He looked at his watch. He had big, competent-looking hands. ‘Damn. I’ve got to go. Conference in five minutes. But it was lovely talking to you…?’

‘Poppy.’

‘Poppy. See you again, I hope. If you’re not strutting down a catwalk in Milan.’

‘I hope so,’ Poppy said. ‘I mean I hope I’m not strutting down a catwalk in Milan, I hope I’m here.’

He laughed and she smiled all morning and not just because he’d left a five-pound tip.

After that, Luke came in regularly and they talked. In the meantime, Poppy started watching the

Seven Thirty News

on Channel 6. She was stunned and impressed to discover her new friend presented it on average four nights out of six. Poppy couldn’t believe she knew such an important man. She made notes on the news stories of the day and plied Luke with questions. Did he think there would ever be a solution to the Israel problem? What was the answer to teenage crime? How could the government sort out the NHS?

‘You’re very sweet,’ Luke said every time. Poppy knew he was being patronizing, but she didn’t much care, though it would have been nice if he’d bothered to answer her properly.

After a couple of weeks Luke asked her if she was free for dinner. She met him at half past eight in a slightly scuzzy Korean place near Channel 6’s headquarters in Pentonville Road.

‘I’d love to take you to the Ritz,’ he said, ‘but someone might recognize me.’

She didn’t care about the Ritz, but she was a bit upset afterwards when, walking up the road, she tried to slip her arm through his and he shook her off.

‘Sorry. But someone might see us.’

Before she could dwell on that, he asked her if she’d like to have dinner again. That happened twice more and after the third meal, they went to bed back at her place, which was happily empty because Meena was visiting family in Bangalore. Then began the most wonderful twelve months of Poppy’s life: twelve months of tangled limbs, sweaty bodies and garbled shouts of ‘I want you!’; of giggly meals in out-of-the-way candlelit restaurants; meals which were far more about alcohol than food; of expensive lingerie and picnics in hotel bedrooms.

Of course Poppy had had boyfriends before, but very few. She’d attended a smart girls’ boarding school in Oxfordshire called Brettenden House and only met boys twice a term when they were bussed in for what the teachers called a ‘bop’. It was at one of these that Poppy, aged fifteen, had met Mark from Radley College. They’d slow-danced all night, kissed in an alley outside the kitchens where the bins were kept and after that had met on alternate weekends in Henley, spending most of the time smooching on a bench by the river. But after three months Mark dumped her because she wouldn’t go all the way. Propelled by a mixture of confusion and spite, the following week she lost her virginity to Mark’s best friend, Niall, under an elm tree in the far corner of the playing fields. The next day he dumped her, telling everyone she was a ‘lousy lay’.

After that humiliation, Poppy avoided all men for a few years. The one to recapture her trust was Alex, who worked in the food department at Harvey Nichols, where she had her first job. Alex cuddled and kissed her a bit, but to Poppy’s great relief he didn’t pressure her into sex. Then she discovered he was gay and they went their amicable but separate ways.

And that was it. Meaning at the grand age of twenty, Poppy was practically a virgin. She had certainly never been in love before. So when it hit her, it hit hard.

A lot of it was the sex. Luke was very gentle with her the first time and very encouraging. He kept moaning ‘Oh God, you’re so beautiful’ which was an improvement on Mark’s ‘Can I put it in now?’ or Niall’s ‘I… uh… awaaargh!’ He showed her what he liked and he asked what she liked and the result was so unexpectedly fabulous that every time Poppy thought about him she felt goose pimples explode across her arms like thousands of tiny fireworks and she forgot even more of Sal’s customers’ orders than usual.

But it was more than just the physical stuff. Luke was a real man. He picked up the tab. He asked her what wine she’d like and, when she admitted she hadn’t a clue, said he’d like to teach her all about varieties of grapes and vineyard soils. He took her to the opera which she pretended to love, even though she spent most of it in a fantasy borrowed from a coffee advert involving her and Luke waking up in some sunny loft apartment and feeding each other croissants. Best of all, after one session on her narrow single bed, he lay back on the pillow and said, ‘How long has that pipe been leaking in the bathroom?’

He was talking about a pipe under the basin that dripped into a bucket like an unsophisticated form of torture. Meena and Poppy had to empty it regularly into the bath. Once they had both gone away for the weekend and the bathroom carpet had got drenched so it smelt like a mangy dog in the monsoon.

‘Months,’ Poppy replied. ‘Meena and I keep asking Mrs Papadopolous to fix it, but she just says, “Yeah, yeah.” I suppose we should call a plumber but he’d just rip us off. Again.’ The last plumber had charged two hundred and eighty-nine pounds plus VAT to fix a dripping kitchen tap and – with some justification – Mrs Papadopolous had refused to reimburse them.

‘I can’t stand it any more,’ Luke said. ‘I’ll bloody do it now. Have you got a tool kit?’

He might as well have asked if Poppy had a guide to quantum physics hidden under the bed. When she said no, he just smiled.

‘Hang on there. I’ll go and get one.’

He returned twenty minutes later, then lay under the grubby bathroom sink grunting and groaning. By midnight the pipe was fixed. Poppy gazed at him with adoration.

‘Thank you, Luke,’ she breathed.

It was such a relief. Poppy had always had to fend for herself. Mum had never been the sort to do her cooking or cleaning or laundry. At an early age Poppy had learnt that if she wanted to eat she had to find something to put in the microwave and if all her clothes were dirty she had to switch on the washing machine, though she never was quite sure how to add powder and what temperature you were meant to set it at, meaning her underwear was perpetually limp and grey until Meena explained about whites and colours. When something broke down, Poppy either called a repair man who usually made a pass at her, then ripped her off, or she just threw it out.