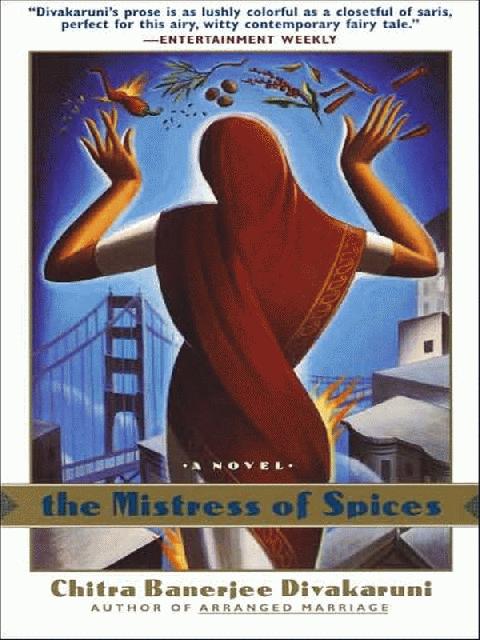

The Mistress of Spices

My thanks to the following persons and

organizations, each of whom helped to make

my dream of this book a reality.To Sandra Djikstra, my agent, who had faith

in me from my first story.To Martha Levin, my editor, for vision,

insight and encouragement.To Vikram Chandra, Shobha Menon Hiatt,

Tom Jenks, Elaine Kim, Morton Marcus,

Jim Quinn, Gerald Rosen,

Roshni Rustomji-Kerns and C. J. Wallia

for their very important comments and suggestions.To the Arts Council, Santa Clara County,

and the C.Y. Lee Creative Writing Contest

for financial support.To Foothill College for giving me, through

a sabbatical, the gift of time.To my family—especially my mother,

Tatini Banerjee, and my mother-in-law,

Sita Shastri Divakaruni—for their blessings.And to Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, whose

grace illuminates my life,

every page and every word.

I am a Mistress of Spices.

I can work the others too. Mineral, metal, earth and sand and stone. The gems with their cold clear light. The liquids that burn their hues into your eyes till you see nothing else. I learned them all on the island.

But the spices are my love.

I know their origins, and what their colors signify, and their smells. I can call each by the true-name it was given at the first, when earth split like skin and offered it up to the sky. Their heat runs in my blood. From

amchur

to

zafran

, they bow to my command. At a whisper they yield up to me their hidden properties, their magic powers.

Yes, they all hold magic, even the everyday American spices you toss unthinking into your cooking pot.

You doubt? Ah. You have forgotten the old secrets your mother’s mothers knew. Here is one of them again: Vanilla beans soaked soft in goat’s milk and rubbed on the wristbone can guard against the evil eye. And here another: A measure of pepper at the foot of the bed, shaped into a crescent, cures you of nightmare.

But the spices of true power are from my birthland, land of ardent poetry, aquamarine feathers. Sunset skies brilliant as blood.

They are the ones I work with.

If you stand in the center of this room and turn slowly around, you will be looking at every Indian spice that ever was—even the lost ones—gathered here upon the shelves of my store.

I think I do not exaggerate when I say there is no other place in the world quite like this.

The store has been here only for a year. But already many look at it and think it was always.

I can understand why. Turn the crooked corner of Esperanza where the Oakland buses hiss to a stop and you’ll see it. Perfect-fitted between the narrow barred door of Rosa’s Weekly Hotel, still blackened from a year-ago fire, and Lee Ying’s Sewing Machine and Vacuum Cleaner Repair, with the glass cracked between the R and the e. Grease-smudged window. Looped letters that say SPICE BAZAAR faded into a dried-mud brown. Inside, walls veined with cobwebs where hang discolored pictures of the gods, their sad shadow eyes. Metal bins with the shine long gone from them, heaped with

atta

and Basmati rice and

masoor dal

. Row upon row of videomovies, all the way back to the time of black-and-white. Bolts of fabric dyed in age-old colors, New Year yellow, harvest green, bride’s luck red.

And in the corners accumulated among dustballs, exhaled by those who have entered here, the desires. Of all things in my store, they are the most ancient. For even here in this new land America, this city which prides itself on being no older than a heartbeat, it is the same things we want, again and again.

I too am a reason why. I too look like I have been here forever. This is what the customers see as they enter, ducking under plastic-green mango leaves strung over the door for luck: a bent woman with skin the color of old sand, behind a glass

counter that holds

mithai

, sweets out of their childhoods. Out of their mothers’ kitchens. Emerald-green

burfis, rasogollahs

white as dawn and, made from lentil flour,

laddus

like nuggets of gold. It seems right that I should have been here always, that I should understand without words their longing for the ways they chose to leave behind when they chose America. Their shame for that longing, like the bitter-slight aftertaste in the mouth when one has chewed

amlaki

to freshen the breath.

They do not know, of course. That I am not old, that this seeming-body I took on in Shampati’s fire when I vowed to become a Mistress is not mine. I claim its creases and gnarls no more than water claims the ripples that wrinkle it. They do not see, under the hooded lids, the eyes which shine for a moment—I need no forbidden mirror (for mirrors are forbidden to Mistresses) to tell me this—like dark fire. The eyes which alone are my own.

No. One more thing is mine. My name which is Tilo, short for Tilottama, for I am named after the sun-burnished sesame seed, spice of nourishment. They do not know this, my customers, nor that earlier I had other names.

Sometimes it fills me with a heaviness, lake of black ice, when I think that across the entire length of this land not one person knows who I am.

Then I tell myself, No matter. It is better this way.

“Remember,” said the Old One, the First Mother, when she trained us on the island. “You are not important. No Mistress is. What is important is the store. And the spices.”

The store. Even for those who know nothing of the inner room with its sacred, secret shelves, the store is an excursion into

the land of might-have-been. A self-indulgence dangerous for a brown people who come from elsewhere, to whom real Americans might say

Why?

Ah, the pull of that danger.

They love me because they sense I understand this. They hate me a little for it too.

And then, the questions I ask. To the plump woman dressed in polyester pants and a Safeway tunic, her hair coiled in a tight bun as she bends over a small hill of green chilies searching earnestly: “Has your husband found another job since the layoff.”

To the young woman who hurries in with a baby on her hip to pick up some

dhania jeera

powder: ‘The bleeding, is it bad still, do you want something for it.”

I can see the electric jolt of it go through each one’s body, the same every time. Almost I would laugh if the pity of it did not tug at me so. Each face startling up as though I had put my hands on the delicate oval of jaw and cheekbone and turned it toward me. Though of course I did not. It is not allowed for Mistresses to touch those who come to us. To upset the delicate axis of giving and receiving on which our lives are held precarious.

For a moment I hold their glance, and the air around us grows still and heavy. A few chilies drop to the floor, scattering like hard green rain. The child twists in her mother’s tightened grip, whimpering.

Their glance skittery with fear with wanting.