The Mayor of MacDougal Street (20 page)

Read The Mayor of MacDougal Street Online

Authors: Dave Van Ronk

The only drawback, from my point of view, was the fear that people back in New York might hear that I was playing in coffeehouses. My compatriots and I had always believed that there was no life form more protozoan than a coffeehouse folksinger. Coffeehouse folksingers were squeaky-clean optimists who brushed their teeth eighty-seven times a day,

wore drip-dry seersucker suits, and sang “La Bamba.” So back home, if you got known as a coffeehouse folksinger, you lost many, many points. It was an embarrassment, but I tried to shrug it off: I was singing in a coffeehouse (or two), but that didn’t necessarily make me a coffeehouse folksinger, did it? Besides, I took consolation in the knowledge that New York was three thousand miles away.

wore drip-dry seersucker suits, and sang “La Bamba.” So back home, if you got known as a coffeehouse folksinger, you lost many, many points. It was an embarrassment, but I tried to shrug it off: I was singing in a coffeehouse (or two), but that didn’t necessarily make me a coffeehouse folksinger, did it? Besides, I took consolation in the knowledge that New York was three thousand miles away.

Then the great day arrived when I received a record-album-shaped package with the return address marked as Folkways Records. My hours in Kenny Goldstein’s basement had finally born fruit, and I ecstatically tore open the wrapping, ready to gaze for the first time on an LP of my very own. The cover puzzled me for a moment: it was one of those great old Folkways covers, a two-tone print full of tubes and vessels resembling the boiler room of the Robert E. Lee. It took a few seconds for the image to sort itself out, but then there was no mistaking it for anything but what it was: an espresso machine.

I went nuts, and if I had had the money to get back to New York right at that moment, I would have dropped everything and made the trip just to break a couple of copies of that record over Moe Asch’s head. I was so enraged that it took several days before I calmed down sufficiently to notice that my name on the label was spelled V-O-N Ronk. By that time I had become philosophical about the whole business, as I have remained ever since.

As in San Francisco, I spent most of my free time in LA hanging out with New York expats. Along with Phil, there was Jimmy Gavin, whom I knew from Washington Square. He had come out a while earlier and was working at a club on the strip called the Renaissance. I went in there one night because I had heard that Jack Elliott was going to be playing, and ran into Jimmy, which was always a pleasure. Even more than the music, though, I remember being struck by the Renaissance itself. It was a real nightclub featuring folk music, and I had never seen anything like that; I had been to the Gate of Horn in Chicago, but only in the afternoon and I had never seen it function. The Renaissance made an incredible impression on me, because there was nothing comparable in New York at that point.

I should mention in this context that it has always amazed me how New York and Greenwich Village hog the credit (such as it is) for the folk music revival. In the 1950s, as far as public performance spaces were concerned,

New York might as well have been Tegucigalpa. Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago were all years ahead of us, each having at least one folk club up and running by 1957 or so. In New York, there was no room dedicated to anything resembling folk music, and no possibility that anyone like me could have any hopes of working more than a few nights a month. It is true that we had some good musicians, but in terms of performance spaces we really got a slow start.

New York might as well have been Tegucigalpa. Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago were all years ahead of us, each having at least one folk club up and running by 1957 or so. In New York, there was no room dedicated to anything resembling folk music, and no possibility that anyone like me could have any hopes of working more than a few nights a month. It is true that we had some good musicians, but in terms of performance spaces we really got a slow start.

As a result, there was very little reason why a folk performer would have chosen to spend time in New York at that point, which may have been why I had never met Ramblin’ Jack. Of course I knew who he was; he was already a legend to us because we had heard the stories about him going out west and becoming a cowboy, then hoboing around the country with Woody Guthrie. A lot of people idolized him, some of them with what I can only describe as a sort of wistful envy, because they were into the music and the mystique but didn’t have whatever it took to pick up stakes and do that. By the time I came on the scene, though, he was long gone from the Village. For most of the 1950s he was either on the West Coast or wandering around Europe with a banjo player named Derroll Adams, and all we heard of him was some recordings for the Topic label in England. He did occasionally pass through New York—sightings were reported from time to time—but for most of us he was more a myth than a person. So meeting him was another pleasure of that LA period.

On the whole, though, I did not like Los Angeles. It was nice to be working regularly and to find some people who were interested in what I did, but there were a lot fewer weirdos than in New York or San Francisco, and I always preferred the weirdos. The kind of people who came out to the folk clubs in LA were more like regular Americans. I could go on about this, but basically the difference between New York and LA is that they are on different planets and are quite happy to be on different planets. So I hated it, mostly because I knew that I was supposed to hate it—when I went back a few years later, I got to like the place very much. Back in 1959, though, I had a chip on my shoulder like a redwood, I was an incredible intellectual snob, and I very rapidly reached the point that I could not wait to get back to New York. Terri was graduating from college in June, and I had promised to be there for that, so after a couple of months I gathered my meager savings and headed back east.

10

The Commons and Gary Davis

W

hen I got back to New York in the summer of 1958, the work situation was about the same, but a lot else had changed. Lee Shaw had passed

Caravan

over to Billy Faier, who had turned it into a serious, scholarly periodical, and she had started

Gardyloo.

(The July issue’s “Anti-Social Notes from All Over” reported that I had shaved off my beard and was “once again a bare-faced boy.”) Meanwhile, the Folksingers Guild was on its last legs. It was still producing occasional concerts for a small pool of Washington Square devotees, but no great revival had yet happened, and the performers were beginning to feel as if all we were doing was taking in each other’s washing. Then our newly appointed treasurer absconded with our small treasury, nobody had the heart to start again from scratch, and the outfit folded with hardly a whimper.

hen I got back to New York in the summer of 1958, the work situation was about the same, but a lot else had changed. Lee Shaw had passed

Caravan

over to Billy Faier, who had turned it into a serious, scholarly periodical, and she had started

Gardyloo.

(The July issue’s “Anti-Social Notes from All Over” reported that I had shaved off my beard and was “once again a bare-faced boy.”) Meanwhile, the Folksingers Guild was on its last legs. It was still producing occasional concerts for a small pool of Washington Square devotees, but no great revival had yet happened, and the performers were beginning to feel as if all we were doing was taking in each other’s washing. Then our newly appointed treasurer absconded with our small treasury, nobody had the heart to start again from scratch, and the outfit folded with hardly a whimper.

At the same time, it was clear that interest in folk music was spreading beyond our esoteric coterie, and not just into the crew-cut hinterlands of the Kingston Trio. About a month after I got back, we all trooped down to Newport to attend the first annual folk festival. None of the Village crowd had been invited to play, except for the New Lost City Ramblers, but nothing would have kept us away. The lineup included all the warhorses of the professional folk world, but also Memphis Slim, the Reverend Gary Davis, and Earl Scruggs. Altogether, it was an absolutely magical event, and oddly

enough, what I especially remember was Cynthia Gooding’s performance the first evening. Cynthia was six feet tall, with flaming red hair, and she was wearing a diaphanous green gown. As she was singing, a fog came in off the water, and the wind was blowing, and the way the lights were set up, Cynthia and her gown were reflected on the clouds. It was the most ethereal visual I have ever seen in my life. The whole weekend was like that. The next evening Bob Gibson, who was riding very high in those days, gave half of his stage time to an unknown young singer named Joan Baez. That was Joanie’s big break, and anyone who was there could tell that it was the beginning of something big for all of us.

enough, what I especially remember was Cynthia Gooding’s performance the first evening. Cynthia was six feet tall, with flaming red hair, and she was wearing a diaphanous green gown. As she was singing, a fog came in off the water, and the wind was blowing, and the way the lights were set up, Cynthia and her gown were reflected on the clouds. It was the most ethereal visual I have ever seen in my life. The whole weekend was like that. The next evening Bob Gibson, who was riding very high in those days, gave half of his stage time to an unknown young singer named Joan Baez. That was Joanie’s big break, and anyone who was there could tell that it was the beginning of something big for all of us.

Meanwhile, Terri’s graduation went off as planned, and within a couple of weeks we had settled into a fifth-floor walk-up on 15th Street.

18

I did not like that much—as Max Bodenheim used to say, I get nosebleeds when I get above 14th Street—but at least it was big enough for two people. Terri had a job as a substitute teacher, and I hung out my shingle as a guitar instructor, attracting maybe ten students a week, and gave occasional concerts. By and large, though, I was still out on the street in search of work. A couple of new coffeehouses had opened while I was out of town, but they were of little interest to me. This was the heyday of the beatnik craze, and what folk music was played in those places was at best a minor adjunct to the poetry. I also had a personal grudge against the main room, the Gaslight Café, because of the hassle it had made for Liz at the Caricature. It was in the basement of the same building, which had been the coal cellar, and the owner, a guy named John Mitchell, fixed it up himself. Mitchell was an incredibly abrasive man, and his construction work—converting the room from a coal bin into an armpit—played hob with Liz’s plumbing and wiring, and he was not gracious about it. Liz was very upset, and she had been our patroness, so I was firmly in her camp. Plus, the place irritated me. It had started hosting poetry readings just after I left for California, with people like Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, but by the time I got back, there was no one of that stature around. I checked it out because Roy Berkeley had a regular gig there, but after hearing these poets bawling and howling, I quickly concluded that it was sheer bullshit.

18

I did not like that much—as Max Bodenheim used to say, I get nosebleeds when I get above 14th Street—but at least it was big enough for two people. Terri had a job as a substitute teacher, and I hung out my shingle as a guitar instructor, attracting maybe ten students a week, and gave occasional concerts. By and large, though, I was still out on the street in search of work. A couple of new coffeehouses had opened while I was out of town, but they were of little interest to me. This was the heyday of the beatnik craze, and what folk music was played in those places was at best a minor adjunct to the poetry. I also had a personal grudge against the main room, the Gaslight Café, because of the hassle it had made for Liz at the Caricature. It was in the basement of the same building, which had been the coal cellar, and the owner, a guy named John Mitchell, fixed it up himself. Mitchell was an incredibly abrasive man, and his construction work—converting the room from a coal bin into an armpit—played hob with Liz’s plumbing and wiring, and he was not gracious about it. Liz was very upset, and she had been our patroness, so I was firmly in her camp. Plus, the place irritated me. It had started hosting poetry readings just after I left for California, with people like Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, but by the time I got back, there was no one of that stature around. I checked it out because Roy Berkeley had a regular gig there, but after hearing these poets bawling and howling, I quickly concluded that it was sheer bullshit.

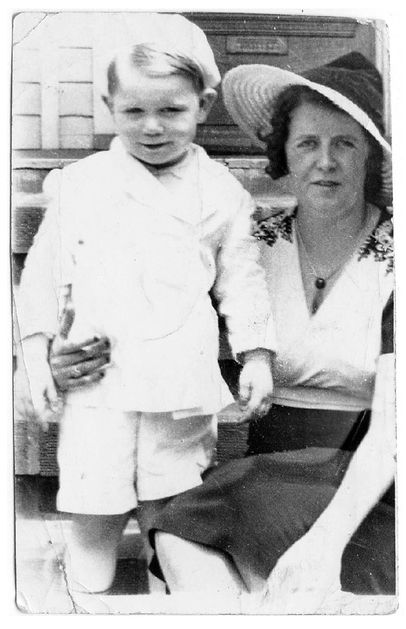

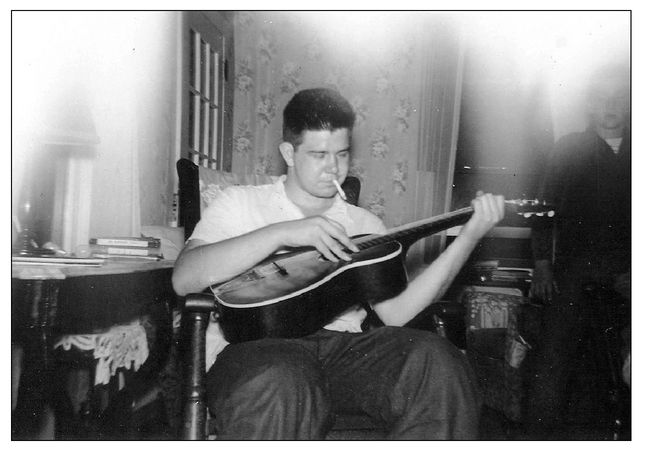

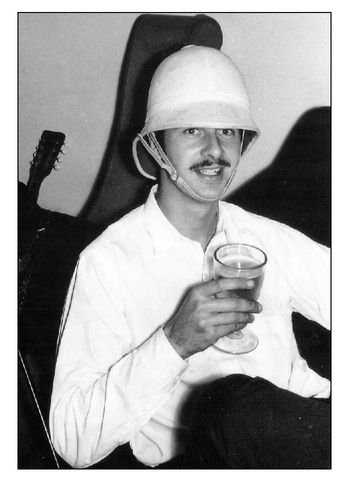

Early Days in Queens:

My mother and me, the Harmonotes’ business card, and portrait of an incipient juvenile delinquent with guitar.

(All photos not otherwise credited are from the collection of Andrea Vuocolo Van Ronk.)

(All photos not otherwise credited are from the collection of Andrea Vuocolo Van Ronk.)

Other books

Disc by Laurence E. Dahners

The Next Best Thing by Jennifer Weiner

The Rainbow Opal by Paula Harrison

Without Warning by David Rosenfelt

The Ides of March by Valerio Massimo Manfredi, Christine Feddersen-Manfredi

Loyal Wolf by Linda O. Johnston

Heated for Pleasure by Lacey Thorn

Poetic Justice by Alicia Rasley

The Crimson Skew by S. E. Grove

Then Came You by Jill Shalvis